A HANDCRAFTED LIFE

The Oliver Cameron Legacy By Margaret Mills

CHAPTER 1 – Beginning

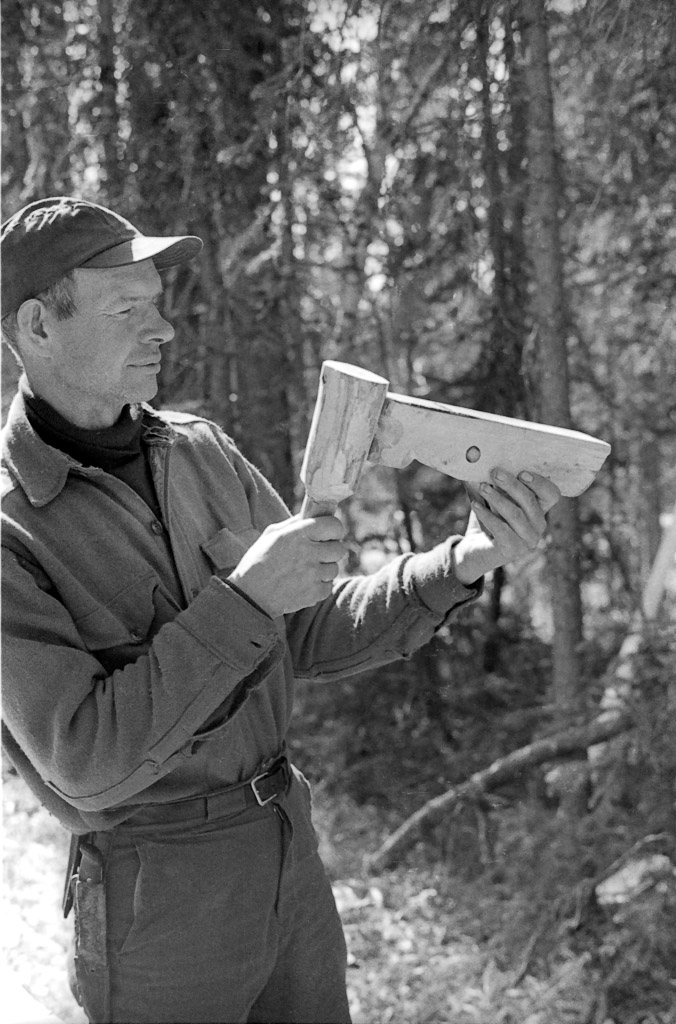

The wolves were howling off to the north again. It was late February, 1991, and 69-year-old Oliver Cameron could hear them through the log walls of his dwelling, a 10 X 12-foot structure dug about four feet into the ground, the walls built up another three feet with stacked logs. It was a snug, warm shelter, with just room enough for his bed, a workbench and the stove. The walls were hung with tools, handmade by Oliver. The floor was covered with wood chips and sawdust.

A pilot friend, Jack Hadden, had flown over that morning to check on the two isolated home sites— Oliver’s plus Dennis and Jill Hannan’s a half mile distant— and reported via radio an old wolf had been hanging around the nearest town, Minchumina, killing puppies. No one had an opportunity to shoot it yet. While Oliver duly reported these wolf activities in a letter to his daughter, Dorene, they did not alarm him. Just now evening chores were his main focus: he needed to get in more snow to melt for water, cut up the firewood he and his dog, Pack, had gotten in the day before, and to bring in another piece of frozen moose meat to cut up for kauk and to dry behind the stove he had fashioned from a five-gallon metal can. The weather was warming up – it might reach 30° in a day or two – so the meat would be soft enough to work without warming in the house first.

His foot was better. The previous fall, while hunting, he had injured his foot and had to hobble about with a cane. He was starting to recover when his feet got tangled with the cane and he fell, severely straining his leg muscle and fracturing a rib. Regular soaking of his foot, which tended to swell if he did too much, and taking it easy over the winter had improved things, but he still was not walking far. A bit later in the afternoon he planned to take a little stroll—not more than a mile, yet—and probably end his jaunt at his neighbor’s house. While Jill’s husband Dennis was away working to earn some cash to tide them over the year, Oliver kept a protective watch over her and their two young boys. He had spent some time babysitting just that morning so she could get a much needed run with her dogs and sled. She too, was recovering from back and hip problems caused by an old ankle injury and exacerbated by too much lifting.

He and the boys were working on a mountain banjo, fashioned from pieces Oliver had cut from spare bits of wood he had. Now that the banjo was starting to take shape, the boys were getting excited, and all of them were curious to see how it sounded when finished.

At 2:00 Oliver set aside his letter writing and turned on the radio to listen to news of “Desert Storm,” just days from a cease-fire. Oliver might be isolated, 30 miles from the nearest airstrip and 150 miles from the nearest city, Fairbanks, but he kept as informed and up-to-date as possible. Mail was flown in on a frequent if somewhat erratic schedule. He had radio contact with the handful of neighbors in the vicinity, and listened to the news. Even so, it was a very isolated existence.

How—and more importantly, why—did a nearly 70-year-old man in mediocre health come to be living alone in the unpopulated interior of Alaska? Oliver’s own words sum up his mindset:

I am not much a part of our culture and don’t practice the careless ways they have adopted to any great extent. I have to do what is necessary to survive with the means of the energy, perspective, and materials available. – Oliver Cameron

This is his conviction in his later years, but how did he arrive at this place, both geographically and spiritually? What is Oliver’s story?

Since we must begin Oliver’s story somewhere, let us begin with a young couple born in the British Isles. James Cameron was born in the parish of Ardnamurchan, Argyll, Scotland in 1815. Ardnamurchan is a 50-square-mile peninsula in the Scottish highlands, noted for its beautiful, wild, undisturbed nature. Even now the population is sparse, consisting mostly of fishing villages and sheep crofts. James left this rural highland area to travel to the United States in1852, sailing from Glasgow, Scotland, to New York.

Annie Bennett was born in Newcastle Upon Tyne, England in July of 1830. She came to the United States as a teenage girl and married James Cameron in Oshkosh, Wisconsin around 1860.

Another tributary to Oliver’s life involves an area that later became the State of Montana. The year 1862 was a pivotal year both for the land that the United States had acquired in the Louisiana Purchase and for the Cameron family. In that year, while Montana was still part of an area known as the Idaho Territory, President Lincoln signed the Free Homestead Act, opening much of the Midwest and West for settlement. The Act encouraged westward migration and the settlement and farming of vast tracts of land in the United States. It allowed those with grit and determination an opportunity to acquire their own homes, farms and ranches, and would be a major influence in the Cameron family for three generations.

Signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln on May 20th of that year, the Act provided settlers 160 acres of public land. In exchange, homesteaders paid a small filing fee and were required to complete five years of continuous residence before receiving ownership of the land. After six months of residency, homesteaders also had the option of purchasing the land from the government for $1.25 per acre. By 1900, 80 million acres of public land had been distributed. 1

As significant as it was, however, the Homestead Act was not the top news in 1862. The overriding issue for President Abraham Lincoln and the rest of the country was the progress of the Civil War, then in its early days. President Lincoln had been elected in November of 1860; Fort Sumter fired upon in April of 1861. By 1862, the country had already experienced the first Battle of Bull Run, and the Union was not doing well. The few Union victories of 1862 were concentrated in the west and orchestrated by General Ulysses S. Grant, in contrast to the eastern campaign under General George B. McClellan.

During these early days, President Lincoln called for volunteers to fight for the Union. While the vast majority of enlisted volunteers were young men, many teenage boys and older men also signed up. James Cameron, the middle-aged Scottish immigrant who had arrived in the United States just ten years earlier, was one of them. He marched off to war, leaving his pregnant wife Annie in Oshkosh, Wisconsin.

It is difficult to trace James Cameron’s military career in the Union army. However, with a pregnant wife in Wisconsin, it is reasonable to speculate that he joined an infantry regiment either in Wisconsin or in one of the neighboring states. Illinois, Iowa and Indiana were heavily represented in the western campaign, eventually forming the bulk of the Army of the Tennessee under General Grant.

In 1862, Grant was the only general actually moving forward and winning battles, beginning with forts Henry and Donelson in February of 1862. If we assume James was with this portion of the army, he might well have participated in the Battle of Shiloh in April, then continued with other Midwestern regiments through the siege of Corinth, Mississippi under General Henry W. Halleck, who led the army before Grant was given total command.

By July of 1862, this portion of the army had fought their way through to Memphis, Tennessee. It was about this time that James was killed, leaving Annie alone to raise their infant son, John James Cameron.

Oliver Cameron was uncertain how they managed in those early days:

“I think that his mother had some kind of a stipend, some income from some property which they owned in Scotland, but that’s all I know about it.”

However, according to other family sources, Annie Cameron refused aid from her husband’s family in Scotland, and returned their letters unopened. An account by Oliver’s cousin, Barbara Silver, gives additional details:

My Great Grandmother, Annie, was born blind but at age 6 gained her sight. She never attended school, but her brother taught her to read the papers. She and her siblings came to America when she was 18 years old.

When my Great Grandfather, her husband, James Cameron, was killed in the Civil War, she refused help from his family in Scotland and made her way as a washer woman. In the 1870 Census, it indicated that her mother Mary may have had a disability, as well.

Annie’s husband James had been married before and had three children from that union. Annie never was asked to care for the step children, but raised the son born to her shortly after her husband, James Cameron, was killed and buried in a trench reportedly in Memphis, Tennessee. 2

John James grew up in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, where he enjoyed skating and iceboating on Lake Winnebago in winter, and sailing in summer. In his home town he also encountered a young woman of French descent, Rose Alexia Bryse, whom he bragged was the prettiest girl in a town of pretty girls. They married in 1883 and resided briefly in Eau Claire, Wisconsin, where they started their family. Sadly, their first child, Chester, died in infancy. The next child, daughter Rose, was born in 1885.

The provisions of the Homestead Act made Montana an appealing destination for many young people who were just starting out, and for older folks as well. The Territory of Montana had been carved out of Idaho Territory in 1884, and was growing. By 1889 it would become a state.

When Rose was five months old the family, including Grandmother Annie, pulled up stakes in Wisconsin and moved to Big Timber, Montana. According to Rose, they endured a “terrible hard winter” that year. Local ranchers lost many cattle, and John James found work skinning cattle that had died in the cold.

A short time later they acquired land on the Sweetgrass River near Big Timber. They lived in a big log house for several years. Most of their 12 children were born there, including Ed, their fourth, born on March 2, 1891.

Grandmother Annie, meanwhile, staked out her own homestead adjoining her son’s ranch and lived there alone. Around 1894 John James sold his ranch and moved onto her property. A couple of years later the whole family moved into town and bought a store.

In 1900 John James moved the family and again tried his hand at ranching, on a ranch along Cottonwood Creek, twelve miles west of Lewistown. Later they moved to another ranch along the same creek. The last of their children, Helen, was born in 1904, and Grandmother Annie died that same year.

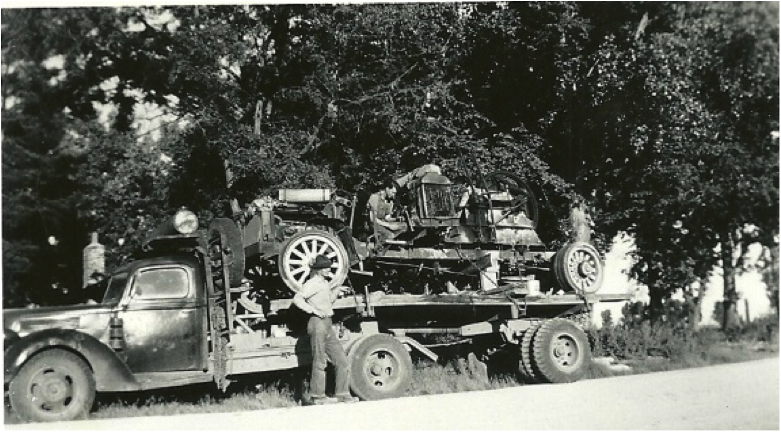

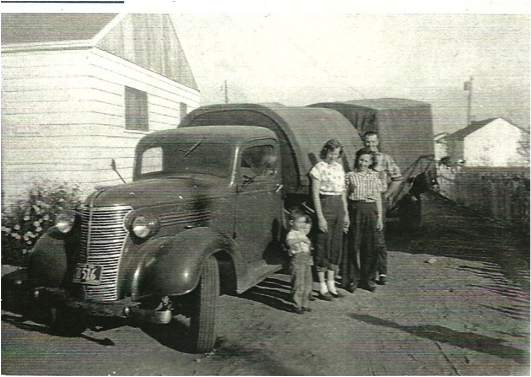

Photo from the Cameron Family Collection.

Ed didn’t share a lot of information about family history or his own youth, but Oliver managed to learn that his grandfather, John James, apparently was not easy to live with—at least, not for young Ed. Oliver speculated that John James, as a boy and as the only child of a slain Civil War soldier and a widowed mother, may have grown up “spoiled.”

Whatever the truth of the matter, Ed quarreled with John James, borrowed thirty dollars, and left home. He was just fourteen years old. Since he’d been raised in rural Montana, he was well equipped to work as a ranch hand, even at such a young age. According to Oliver, it was not uncommon for teenage boys to be on their own and doing a man’s work in that time and place.

After the Civil War, a man named T. C. Power began a number of entrepreneurial enterprises in Montana, later becoming the first senator from the state. One of his investments was a large cattle ranch near the Judith River. To manage the enterprise, he contracted with a ranch manager named John Norris. They named the ranch the P-N Ranch, for Power-Norris.

The P-N Ranch is about a hundred miles due north of Lewistown, Montana. One of the oldest of Montana’s ranches, it continues as a working ranch of historical importance into the present day. Ed eventually made his way to this large corporate ranch to work as a cowboy. By 1916, when he was in his mid-twenties, he was riding line and cooking for roundups.

According to his daughter-in-law, Eula Mae Cameron:

[Ed] told tales of the big Montana round-ups where his contributing art was cooking over campfires and preparing food in a cook tent or from the back of a supply wagon. “Cookie” was a very important part of the operation, and it behooved the Boss to provide a cook that was good. Dad’s pancakes and “mush” were still top-notch when we were sampling them.

In an interview with his daughter, Dorene, Oliver related a bit about life on a big ranch. “Back then there were no fences. The cattle were free to roam in a specified area and were contained by men on horseback riding around the cattle to drive the strays back into their grazing area.”

It seems Ed was the quintessential cowboy, and not one to back away from a confrontation, as Oliver revealed in this story:

This is of a time when the neighboring homesteader saw an opportunity to take advantage of the well-traveled dirt road across his ranch. Ranchers had been using the road many years to move cattle. The only other way to get across was to go a long distance around the ranch. The rancher let it be known that they could no longer take cattle across his property unless they paid for use of the trail. But the trail had been used for so long that the other ranchers believed that it had become a public right of way, which he could not close off.

Dad and his brother-in-law Johnnie Sanford were driving a herd of cattle down this road one day. Johnnie traveled ahead on his horse to make sure that the gates along the side of the road were all closed so that the cattle wouldn’t stray. Dad, coming up behind, encountered the hostile rancher and one of his ranch hands, both carrying pitchforks. The ranch hand walked out in front of Dad’s horse, the rancher approached from the side.

He told Dad, “You will need to take your cattle around. This is my property and is not open for travel.”

Dad was strong, quick and agile. He also was very good at managing horses. He had his horse trained so that he could dismount from either side. Most horsemen dismount only from the left. Dad quickly slipped off the horse on the far side, which was not expected. He slipped under the horse’s neck and knocked the ranch hand to the ground. In the next instant, he knocked out the rancher.

When Johnnie returned over the rise shortly thereafter, he saw a commotion and spurred his horse ahead. As he approached, he saw both men sprawled unconscious on the ground along with their pitchforks.

Johnnie asked, “Are you having problems?”

Dad answered, “No, there is no problem.”

The novelist Zane Grey, who wrote epic western fiction, traveled extensively to research his books. It is not surprising that he might stop by the P-N Ranch:

One of the highlights of those days to Dad was the time Zane Grey came by the ranch to soak up authentic flavor for his novels. I can’t remember which of his novels he was writing then but forever after, Dad was a Zane Grey reader. –Eula Mae Cameron

Ed took note when a young woman named Pansy Viola Wood came to work at the P-N as a domestic. Her family had relocated to Montana from Minnesota when she was a young teenager. By the time she met Ed, she was in her late teens or early twenties.

While Ed had received a third grade education before striking out on his own, Pansy had spent more time in school and with an aunt “back east,” and been educated in some of the finer things of life, such as how to keep house properly and set a table.

Needless to say, the smart, self-made cowboy and the refined young woman gravitated toward one another. We know little of Ed and Pansy’s courtship, except that Ed made her a leather braided bridle and quirt during his spare time while riding line in the winter. According to Eula Mae Cameron, both Ed and Pansy were horse lovers. Much of their courtship took place on horseback, so this was certainly an appropriate gift. In 1917 they married in Hilger, Montana, where John James and some of the children were running the post office.

That was another pivotal year for Montana as well. There had been a huge influx of settlers and homesteaders into the state during the years when John James and Rose were working their ranch, but 1917 saw the beginning of a drought that convinced many of the state’s farmers to move on in search of better farming and living conditions. Records suggest that 65,000 of the nearly 100,000 homesteaders left the state between 1918 and 1925. This pushed Montana’s economy into a depression well before the Great Depression began in 1929.

Many relocated to Washington, Oregon and California. John James, Rose and their younger children moved from Hilger, Montana to Blaine, Washington.

Blaine is a small town in the extreme northwestern corner of Washington State. The northern edge of the city limits lies along the Canadian border. The town, established during a short-lived gold rush on the Fraser River in British Columbia in 1858, was incorporated about 1890. By the early 20th century, the town had five fish canneries, including the large, well-known Alaska Packers Association facility. Employment was also available in timber and agriculture. John James found a job in the lumber industry, and worked and prospered in Blaine for several years.

Meanwhile, Ed was finding that work as a lineman and cook for the P-N did not pay enough to fulfill the dream of owning his own ranch. The newlyweds shortly joined the rest of the family in Blaine. Ed found work on a ranch, and still hoped to buy land of his own. However, finances were still an issue for the growing young family, so he later went to work for a small sawmill near Bellingham.

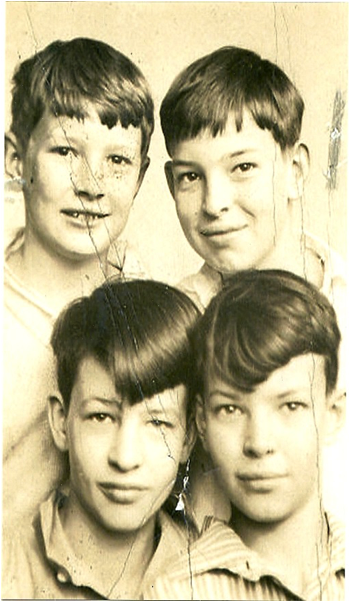

As was common for the times, Ed and Pansy had begun their family shortly after their 1917 marriage. Tragically, their first child, a son, did not survive. Their second child, Oliver E. Cameron, was born July 15, 1921 in Blaine.

Photo from the Cameron Family Collection.

Oliver related that he had health problems as a baby:

I almost died when very young, perhaps less than a year. I had dysentery along with many other babies at that time. I don’t know what disease it was and there was no cure known. Because antibiotics and sulfa drugs weren’t developed yet at that time, the doctor told my folks that the only hope for saving me was to not feed me for a week or so, to only give me water. My impression is that I was a nursing infant at the time.

After about a week, Mom couldn’t stand doing this to her baby and nursed me just a little bit. The dysentery started again, which prolonged the time for which I couldn’t be fed. Amazingly, I survived and recovered on my own. There were a lot of infants dying from this. After that, I was put on a bottle.

To the east, near the little town of Snoqualmie, Washington, the Snoqualmie Falls Lumber Company began operations around 1917, and was soon acquired by the lumber baron Frederick Weyerhaeuser. It was the second all-electric sawmill in the nation, and would continue to be a major employer and provider of lumber products for nearly a century.

Responding to a company advertisement, Ed wrote and applied for the position of sawyer—a highly skilled job that paid well—and got the job. He moved his family, which now included Oliver’s younger brother Keith, to Snoqualmie Falls.

A company town for mill workers had been built across the river from the town of Snoqualmie. It included such amenities as a hotel, a community center, a 50-bed hospital, a barber shop, and rental housing of various sizes. The Cameron family began their life there in a four-room house, graduated to a five and then a six room house as the family grew, and eventually moved into the largest of them all, the original farmhouse in a location known as “The Orchard.” The location had once been an actual orchard, and fruit trees still adorned some of the back yards.

According to the Snoqualmie Valley Historical Society, there were two mills. The main band saw at Mill #1 could handle logs up to eleven feet in diameter. Mill workers routinely processed the large-diameter old growth timber of the Northwest forests, a difficult and often dangerous activity.

Ed had one of the most demanding and intricate jobs in the mill, that of the gang rip saw operator. The gang rip saw consisted of several blades moving in various directions to cut the big logs into lumber. According to Oliver,

He had a bunch of levers there that would move each saw in relation to the others. He had to be watching all the time for things like barbed wire that had grown into the tree, or stones that the spraying hadn’t gotten rid of. He could tell by the sound of things if he was just cutting wood, or if he could hear it cutting something else, he would back off and look to see. That was a job that required a lot of constant concentration. He worked eight hour days. The mill worked three shifts.

Ed remained a man of toughness and action. With his extensive background as a Montana cowboy, he was not afraid to deal with a threatening situation as needed. Oliver obviously admired these traits in his father:

A relatively new employee was running the machine after Dad, and one day felt like Dad was pushing him. He couldn’t keep up with Dad. That whole mill was designed to operate at a certain pace. That fellow wasn’t up to the job yet or wasn’t able to do the job, and this slowed down the whole mill. This fellow one day got angry and picked up a two-by-four to hit him. Dad saw him coming, jumped him, knocked him down and took the board away from him.

There was a rule at the mill that whenever there was a fight, both men would be immediately fired. Dad, knowing this, gathered up his things and turned off his saw, shutting the entire mill down. He walked up to the mill office, which was quite a ways, and asked for his paycheck. The foreman immediately started looking to see why the mill was shut down.

After hearing the story, he said, “Why don’t you just go back to work?”

While Ed was getting established in Snoqualmie Falls, his parents moved to Bellingham, Washington, about 110 miles to the west. Ed’s father was now in his sixties, but the two men were still estranged.

Oliver relates that the only time Ed went to visit his parents was at his mother’s request. She was ill and wanted to see her son, “Eddy,” and his family:

Dad loaded up the family and took some extra gas cans and tied them on the running board. He took off after work and drove all night until he used up all of the gas. Then we had to wait by a service station until it opened to buy more gas.

After we got there we stayed with Dad’s brother-in-law and sister. They had two kids that were older than us….Grandpa didn’t want to be around Dad. He wanted to see us kids.

Those cousins took a couple of us to the cigar store that Grandpa owned. He was a big man, rather portly. There was a cigar store Indian [carved wooden statue] out in front of the place. He [Grandpa] gave us a couple pieces of candy.

Rose Alexia Cameron died in Bellingham in 1932. John James went to live with Ed’s sister, Esther, in San Diego, California. He died in 1933.

Photo from the Cameron Family Collection.

Health problems seemed to plague Ed’s family. Pansy developed tuberculosis when her children were still very young. She did recover, after spending some time away from the family to rest, but by

Oliver’s account she was never again in good health. Her frequent pregnancies may have contributed to her frailty. Oliver himself had a bout with polio when he was about six, leaving him with one leg shorter than the other.

He was eight years old when the Depression began in 1929. Fortunately, the mill continued to operate, but with the economic hard times and his growing family, Ed was never able to save much money. There would eventually be six children: Oliver, Keith, Phillip, Adrian “Carol,” Jessie Mae, and Dean “Del.”

Although Ed was never able to buy his dream ranch, he was able to acquire about six acres of “stump land” when Weyerhaeuser made logged-off land available to their employees at prices they could afford. Oliver recalls Ed paying something like twenty dollars down and one dollar per month to purchase his home site. This was bare ground, or rather ground with large stumps still dotting it.

In those days, loggers would use springboards to enable them to cut a tree well above ground level, leaving behind a stump as high as ten feet. The owners of such “stump farms” would salvage the wood for building material, such as hand-split cedar shakes, and for firewood.

Oliver began what was in effect a long apprenticeship in how to convert raw land into a functioning homesite:

I spent many hours of my youth working with Dad to build up our place on this land. Dad would give a task and, being a quiet, calm man, would leave me on my own to figure out how to do it. If more explanation were needed, Dad would give it. I learned to dynamite out the stumps for farmland; I built a belt saw to cut firewood from an old car engine. The flywheel was crafted from the wheel rims. I loved the intrigue of this type of work.

He worked closely with his father, learning the details of engine repair and craftsmanship simply by being with his father as the family worked to build and maintain their home:

I remember helping Dad build a chicken coop. across that alley behind the houses, he built that chicken coop back there. Of course, that was still during hard times. There was a row of garages that went with each set of houses…I remember going there and helping Dad or watching him work on the car. The engines didn’t last long like now. If it lasted 20,000 miles you were doing good. Anyway, Dad was something of a mechanic too. I remember when I was little, him being under there, and [me] handing him the tools.

Even when Oliver was not shadowing his father, he was alert, observing and learning from the activities going on around him:

When I started school at six years old, before I had polio, there were a couple of carpenters building houses at the end of the row of houses that I had to go by. I saw what they did on my way to school and then when I came home again. I watched them laying joists, subfloors, putting up the walls. And that’s when I learned to build houses. When they went home, I would go over there and pick up the nails laying around on the ground so I would have nails.

In addition to acquiring his “real” education by observing the work of the men around him, Oliver began collecting tools and working with them while still a young boy. This fascination with tools, their design and manufacture, would become a major focus of Oliver’s life. Even at this early age he was exhibiting the innate engineering and design talents that would mark his life:

When we were at the 5-room house, I was wandering out in the trees out back. I came across a broken crosscut saw. I brought the longer piece home. The loggers would leave files sticking in a stump. So, I had a collection of files. I just about wore the teeth down on that saw learning to sharpen it.

A nearby commercial dairy farm, Meadowbrook, had a well-equipped blacksmith shop. The blacksmith took time to contribute to young Oliver’s education. Oliver tells of making his own knife blade from a bit of soft iron from an abandoned car top:

Of course it was just very mild steel, maybe not even steel. So, naturally it wouldn’t hold an edge, so I asked my dad about it.

He said, “Take it over to the blacksmith at Meadowbrook,” so I took that knife and was standing inside the door watching the blacksmith working, with the forge going, and he asked me if I wanted something. I showed him my knife and told him the problem, and he asked what I had made it out of, and I told him.

He wasn’t encouraging, but said, “Let’s give it a try, maybe we’ll luck out.”

He heated and cut the blade. When he pulled it out…he touched it with a file, and then he took a little time and explained to me the difference in iron, in that steel is iron with a certain amount of carbon worked into it, and this piece had practically no carbon in it, so he said there was not a whole lot that could be done about it.

That was when I was six year old, I guess, and I remembered what he told me….

He did remember, and later applied his knowledge to a broken piece of saw:

Anyway, I started fooling with tempering it. In those days most men knew quite a bit about that sort of thing; they grew up on homesteads and so forth. My dad gave me a few pointers. He said get it red hot, but don’t let it start shooting sparks out of it, because that’s burning out the carbon. Then plunge it, and then you have to heat it up again, but not so hot this time; heat it until it’s maybe a dull cherry red and plunge it, and that will draw the hardness out of it. So I tried it again, and heated it just a little hotter and let it cool, and I did have a workable piece of equipment. And that’s pretty much the way I learned.

At this point, Oliver was in second or third grade. Unsupervised, he heated his saw project with a blowtorch propped in a stack of bricks to create a small furnace.

Of course, Oliver participated in all aspects of life on a small farm. He helped with everything from washing dishes to chopping firewood and tending the farm animals. While he resented his mother’s insistence on formal table settings, and the extra dishwashing it created, he recalled milking cows in a slightly more favorable light:

As soon as I was old enough I would milk the cows because Dad was usually working nights. It took me twice as long as Dad to milk. We got beet pulp from the beet factory. That was part of the mash we fed the cows. One cow got into the barn and ate a bunch of that beet pulp and foundered itself. I went down in the morning to milk, and it was laying down all bloated.

I woke Dad up, and with a pocket knife he measured from the spine, and from the hip he measured with his hand. He jabbed the thin blade in and gas came out. Pretty soon, the cow got up and I milked it….

Overnight they would lay with their tail in the gutter, and wanted to slap it around, so we would tie the tail to the far side to control it. Down on the creek Dad built a milk house. We could set a can of milk in the creek or in the milk house shaded by the trees.

We put the milk in big pans and they went on shelves so the cream could rise. I would strain the milk into those pans and then skim the cream off the other pans. The milk would sour quicker than the cream. I would scoop the cream up and take it to the house, and Mom or whoever would make butter out of it, and then [with] the clabbered milk we would make cottage cheese. We always had more than we could use. The clabbered milk went to the chickens. Sometimes we would make cheese.

He also learned to garden and to harvest wild food from the Pacific Northwest forests. This included grass and clover for a bunch of angora rabbits the family owned for a time. Being the eldest child with parents who were overworked and in poor health, he took on many of the child-rearing duties, such as waking up his siblings, getting them ready for school, and preparing their breakfast and school lunches.

By his own account, Oliver himself only went to school out of obedience to his folks. He was aware that his education was important to them, and something for which they sacrificed. Nevertheless, he felt there was little benefit to formal education, and did not put his full effort into getting good grades:

I didn’t like school anyway. It didn’t make much sense to me. Dad didn’t have that kind of education and yet during the Depression the neighbors came and asked him how to do things. A lot of it was just stupidity as far as I was concerned. I learned what I wanted to learn from it.

Oliver remained true to his penchant for self-directed learning. Later in life he would confess:

Reading has been my whiskey. It’s not just any kind of reading; it’s been reading all kinds of things. That, and then the influence of my father, who was a very adaptable person, and growing up during the Depression when he had the initiative and the know-how to get hold of a piece of property, unimproved stump land, and turn it into a home….

In addition to doing chores and homework, Oliver held various part-time jobs before he graduated from high school. He worked at the traditional jobs that were open to teens in that time and place. He picked fruit; he worked at a garage pumping gas. The latter job enabled him to buy his first car, which he cut down and turned into a pickup. This in turn opened the way for additional entrepreneurial pursuits:

Then I cut shakes, shingles. I would go out where they had logged out and find a cedar long butt or big stump and cut it into shingle bolts or shake bolts and sell it to a shingle mill. I would cut firewood out like that too, and sell it by the cord.

His last summer in high school, Oliver got a job as a section hand with the Northern Pacific Railroad:

We had a gas car, a little spider-like thing that runs on the rails. It has a couple of ties so that you could pick it up and turn it around to get it off the tracks to let the train go by. If we were working in a place where we couldn’t see the train coming, we had something like a cap gun cap that we would sit on top of the track so that when the train hit it, it would make an explosion that would let us know the train was coming.

The wooden tracks would get rotten and have to get replaced. That was one of the biggest jobs. We’d dig out right under the tie and put the new one in, and then pry it up against the rail, and then shovel gravel under it so that it was tight against the rail. There was a little plate on top of each tie for the rails to sit on with holes in them for spikes. A spiking hammer has a small head and is double-ended, so you have to be pretty accurate with it. I was good at that. I got to drive the spikes. That was just because I was raised using tools.

There was a little gap left between the ends of the rails. In the summer they expand and when cold, they contract. There is nothing to hold them, nothing to keep the rail from moving forward or sliding down hill. There is a kind of a C clamp you put on one side and pull it up on the other, then clinch it down on the rail to keep it from moving downhill. The rails manage to creep downhill anyway, so you would have to cut a half a rail or so off so that the rails wouldn’t expand and buckle. That was another of our jobs.

I enjoyed that job! Hard work!

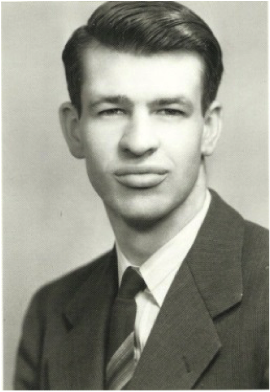

Graduation day came. Oliver wryly suspected he was given his diploma to get him out of the school system, in which he obviously had little interest. True or not, Oliver was now a high school graduate and quickly made his way to full-time work in the wider world. He had a little time to experience life as a young man in Washington State before events in that wider world spun his life in a different direction.

He worked a handful of odd jobs, then moved about seventy-five miles due west of his Snoqualmie home to Bremerton, Washington, where he took a job at the Bremerton Concrete Works:

My first job there was running a machine that made concrete blocks. You had a form and you filled it with green cement, and then it had to be tamped. That machine I was operating tamped the pasty cement. It wasn’t really runny.

And then they got an order for guard rail posts. They were about 14 inches in diameter and seven or eight feet long. They weighed about 55 pounds green. I would grab one, bend my knees, pull up towards my chest, flex my legs. I had good legs. Someone would kick the pallet out from underneath, and I would set it down.

While working another machine, Oliver experienced an industrial accident that gave him a bit of empathy for the blind. Although his injury fortunately resolved itself after a few days, he never forgot the experience:

I was operating a batch plant filling ready mix trucks. The cement came up a conveyor on sacks and spilled off the conveyor into a chute that brought them to a platform, right handy there. The hopper above that mixer was a scales. You pull a lever, and a certain amount of gravel would go in, and pull another and sand would go in, and pull another and water would quirt into that hopper, then you would reach around to your side, take your sharp trowel, and slash the cement sack. You grabbed both ends, picked it up, turned around, and tipped the thing over and pull the two ends together so that the cement dumped into the hopper.

Trucks are waiting, so you are in a hurry. I reached around and cut a bag open and stuck my trowel in my holster. Then leaned over to pick that thing up and here come another bag of cement down and hit the open end of my opened sack and made a geyser of cement, right in my face.

The cement is really finely ground. It felt smooth and didn’t hurt, but as soon as it started mixing with my tears, that was something else again.

I felt my way down and went into the office. They kept a first aid kit there with a little eye cup. I tried to wash my eyes out. Somebody took me to a doctor. They irrigated my eyes again. Then they bandaged my eyes so that the light couldn’t get in. I had to have that bandage for two or three days. Even after that, it took quite a long time before my eyes quit being sensitive to light. Of course, it was not hopeless for me. I knew that I would be able to see OK, but it sure gave me a feeling for what blind people have to do.

He quit soon after, feeling that the pace and pressure of the work were too much. He went from Bremerton to the Olympic Peninsula to be part of a firefighting crew on the Dosewallips River, where he was more in his element. Even his early childhood efforts to learn saw sharpening came in handy:

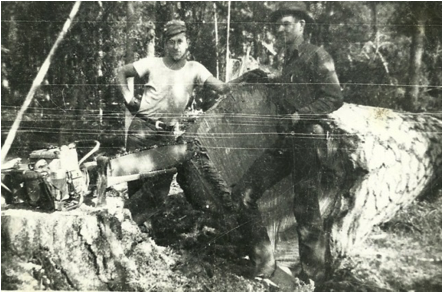

They had been fighting that fire for a couple of days before I got there. We were making a fireline around part of it. We were using a Pulaski, and they had a box of files in the cook tent. I put three or four of them in my pocket. There were some fallers falling snags. I was sharpening my Pulaski. Those fallers saw me sharpening that, and they wanted me to sharpen their axes, so I did.

Oliver and another young man were left to monitor the fire after the worst was over. They spent their days hiking mountain trails searching for and extinguishing “hot spots.”

During this time Oliver also worked for the Service Fuel Company, which sold firewood and coal. They used a large buzz saw to cut firewood. Oliver described the system:

The buzz saw had a 1-cylinder engine, a putt-putt…The way you started it was by giving those flywheels a good pull against the compression. I wasn’t very heavy, probably 155 pounds, but just heavy enough to pull the flywheel over to get the thing going. When the piston goes down, some gases go in. When it comes back up, it compresses that gas and then a spark explodes. When we pulled the flywheel it would start it running. Running that big buzz saw was one of the biggest jobs I had there.

He also shoveled coal to sell to homeowners by the sackful. This job ended when a relative of the owner wanted the position.

But by then the world was at war.

_______________

1Act of May 20, 1862 (Homestead Act), Public Law 37-64, 05/20/1862; Record Group 11; General Records of the United States Government; National Archives.

2Ancestry.com by TANDBSILVER, Barbara Silver re: Anne Bennett 1830-1904. Used by permission.

CHAPTER 2 – The War

Oliver had barely finished high school when the Nazis invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, and he had just turned 20 when the Japanese bombed the U.S. Pacific Fleet on December 7, 1941. As Tom Brokaw wrote in The Greatest Generation, “When Pearl Harbor made it irrefutably clear that America was not a fortress, this generation was summoned to the parade ground and told to train for war” 1

As a man who was young, single, and fit, Oliver was a perfect candidate to serve his country in the military. As soon as he heard the news on the radio, he knew without a doubt he would be drafted, and accepted that fact unflinchingly. The expected notice came in 1942.

He reported to Fort Lewis, near Tacoma, Washington for his physical exam. Since he’d had some previous radio experience and was interested in the field, he was sent to Sioux Falls, South Dakota, for training to become a radio operator on a B-24 (heavy bomber).

The Sioux Falls school was brand new, built in 1942, and relatively small, with only 40 training aircraft at the field. On the B-24 the radioman also doubled as a gunner, so Oliver was sent to gunnery school at Davis-Monthan Army Air Field near Tucson, Arizona when he finished his radio training.

Oliver described some of his gunnery training:

We had some simulated training thing there that you sat in just like you was sitting in an airplane. There was a screen and planes would be coming at you. You had guns there to shoot those planes down. They had some small training planes that had a gun in them. We would ride in the back of that, shooting. A bigger plane would fly dragging a target that we would practice shooting at. From there I was a flight radio instructor for a little while, then they found crews for us.

The sturdy B-24 bomber had a range of 2,000 miles, flew 300 miles per hour, and carried 9,000 pounds of bombs. Its ten crewmembers wore electrically-heated gloves, suits and boots, which did not always function correctly. For these young men, all in their late teens and early twenties like Oliver, crewing a B-24 bomber was a high-stress assignment. Not only were their working conditions inside the B-24 cramped and uncomfortable, but the life expectancy of the crews and planes was short—about 35 bombing missions.

In mid-1943, as Oliver was completing his training to crew a B-24, Italian dictator Benito Mussolini was still allied with Adolph Hitler in prosecuting total war against the United States and the other Allies. That same summer President Franklin D. Roosevelt, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and U.S. General George Marshall, meeting in Casablanca, decided to invade Italy. By mid-August Mussolini had fallen, generals Patton and Montgomery had taken Sicily, and the Italians had surrendered. The Allies were ready to move on to the mainland.

However, although the Italians had officially surrendered, the Germans still had control of most of the country. The conflict to claim it was long, difficult, and bloody as the Allied soldiers fought their way up toward Rome from the southern tip of Italy. This Allied toehold in southern Italy provided a base from which to bomb the Balkans and parts of Europe formerly out of reach. The Allies hurriedly put together the B-24 bomb crews needed to take advantage of this opportunity. The 449th Heavy Bombardment Group was formed in November of 1943 in southern Italy, and Oliver, newly qualified as a radioman and gunner, was assigned to a crew.

Oliver, who had spent his entire life in the State of Washington, had recently seen some of South Dakota and Arizona courtesy of the military. Now his horizons would broaden considerably, beginning with a trip to Florida.

Oliver and his crew began the journey to Italy from Florida in a B-24 that had auxiliary fuel tanks in the bomb bay and on the wings, but even so, having enough fuel to reach their next stop was sometimes a near thing. A strong headwind on their way to Brazil made fuel tight, but they landed safely. They were stuck in Brazil for a week by bad weather over the Atlantic. It was Christmas the week they were grounded in Brazil. Some of the men “appropriated” a turkey and they celebrated the holiday.

“They were pretty good at that snitching business,” Oliver said in later years.

When more B-24’s arrived, and the weather cleared, they flew on to Africa. The trip was not uneventful. Once, Oliver was sitting at his radio operator’s position when the plane hit a vacuum pocket and suddenly dropped 1,000 feet straight down. He could see lightning skittering over the outside of the plane, and the noise forced him to remove his radio headset.

There was only a dirt runway in Dakar, Senegal, but the group managed to land safely, although Oliver witnessed planes sliding off the runway and having to be towed back on.

From Senegal, they flew on across the Sahara Desert where Oliver—born and raised in the wet Pacific Northwest— saw nothing but sand and sand dunes as far as he could see. They landed at Algiers, in northern Africa, and waited for the whole group to assemble, and then flew on across the Mediterranean Sea to southern Italy and the town of Grottaglie.

During the first part of World War II, Grottaglie, Italy, and the nearby airport remained under the control of the Italians. Later in the War, the German Luftwaffe took it over; as a result, the British Royal Air Force bombed it heavily. After the Allies invaded southern Italy in 1943, they rehabilitated the bombed-out airfield and used it as a base for heavy bombers. The 449th with their B-24 Liberators was one of the groups that made use of the airfield beginning in January of 1944.

Image from the website of the 449th Bomb Group Association3

Oliver was among those first to land and set up camp on the bombed-out airfield outside Grottaglie, which lies in the heel of the Italian “boot”:

The air strip was patched up, but the hangar was bombed up, lots of tin hanging on it. We got there ahead of our supply ship – no tents, short on grub. We were sleeping in the hangar. Some of the fellows got a bushel of tangerines. Everybody ate too many of them, except me. I knew what would happen. All night long you would hear the tin rattling, somebody going out to relieve himself. Finally we had tents. We set up the tent for each crew. It was chilly weather, not really comfortable. Chappy and Swede, the engineer and assistant flight engineer, made a stove to burn flight fuel. Other guys copied, but didn’t really know what they were doing. Some of them burned down their tents.

Oliver and his fellow airmen made trips into town for food, drink, and recreation. There he befriended a shoemaker, his wife, their daughter (whose husband was in the Italian army), and her small child.

Each squadron in the 449th consisted of six planes. Oliver had originally been assigned to the 717th squadron, but he and some other men were transferred to the 719th, which had suffered heavy losses. There he remained until he finished his time.

Oliver’s plane was called Dragon Lady #2. The original Dragon Lady was salvaged as scrap after hitting a brick wall while landing. (Fortunately, nobody on the crew had been injured.)

In 475 days of combat the 449th lost 103 bombers, 383 airmen were killed, 363 were taken prisoner, and 159 were shot down behind enemy lines and evaded capture.4

On April 4, 1944 the 719th was ordered on a bombing mission to Bucharest, Romania. The squadron consisted of Dragon Lady, Consolidated Mess, Dixie Bell, Paper Doll, Born to Lose, and one unnamed plane. It was a whole wing mission, so other groups were to rendezvous with them. The mission was called off when it was discovered that vital information about the mission had been leaked, but somehow Oliver’s group, with his six-plane squadron bringing up the rear, was not notified and went on alone. They were met by German fighters with belly tanks. When the Germans spotted the Allied planes, they dropped their belly tanks and attacked. Oliver, acting as gunner, started firing as soon as they were within range. His pilot could see the tracers were falling short and called Oliver on the radio to tell him to raise his sights. Oliver complied, and downed the enemy plane. When it was over, their plane had quite a few holes, Oliver had used up all of his ammunition, and he had held the trigger down too long and burned out one of his barrels. Of their squadron, only Dragon Lady returned from the mission. The other five were shot down, their crews killed in action or taken prisoner.

Dragon Lady flew a couple more bombing missions once new crews and aircraft had replaced those lost over Bucharest.

Then, on April 12, 1944, the 449th, part of the Heavy Bombardment Group’s 47th Wing, was ordered on a mission over Austria.

They were to attack an aircraft factory at Winer Neustadt. They were successful in dropping the bombs, but then came the counterattack. The Allies used a variety of techniques during their bomb run to confuse the enemy fighter planes and the heavy artillery on the ground. One of these tactics was the use of “window” or “chaff,” shredded foil that interfered with the enemy radar. This worked a few times, Oliver recalled, but eventually someone down there “smartened up.”

Unfortunately, the enemy got wise to their “chaff” while Dragon Lady’s bomb bay doors were open, since they had just dropped their bombs on the target. They took a burst of flak just under the open bomb bay doors. This damaged the hydraulic system so the doors would not close, nor could they lower the flaps or landing gear. Dragon Lady fell out of formation.

They flew out of the flak area, but two ME-109 planes attacked them, one of which was shot down by one of Dragon Lady’s waist gunners. However, the enemy gun range was longer than that of their 50 caliber machine guns, and the remaining enemy fighter took out Dragon Lady’s other engine. At 16,000 feet their pilot, Jack, banked the plane steeply and aimed for some hills while trailing smoke from two engines.

They flew into some clouds.

In his book, Of Men and Wings, D. William Shepherd describes what the other squadron members witnessed:

Three 449th B-24s fell victim to the aggressive enemy fighter attacks. Ship #10 [Dragon Lady], manned by Olson’s crew flying in position ‘A-1-5’, “started losing altitude”—probably due to flak damage—as the formation made the rally. The enemy fighters immediately pounced upon the stricken aircraft which had the #4 engine feathered and one wing covered with oil. Ship #10 was “last seen making for clouds just beyond target, time 1207 hours.” 6

The sight of Dragon Lady flying into the clouds and trailing smoke was the last the crews in the flight group would hear or know of Oliver’s crew for several weeks.

Once in the cloud cover, the pilot pulled the plane up so abruptly the crew was pushed back hard in their seats. It was a rough, but cautionary maneuver. He didn’t know how high those hills hidden by the clouds were.

Their goal was to get across the river on the north side of Croatia and crash land in Yugoslavia. If they could escape capture by the Germans, there were partisan groups in Yugoslavia who might help them.

Dragon Lady and crew did make it to Yugoslavian territory, but just barely. Oliver described details of the crash landing:

We had one inboard engine wind-milling, which sets up a lot of drag. With the bomb bay door open creating more drag, we were going down. We clipped the trees on the north side of the river, crossed the river and set it down in a pasture. That open bomb bay plowed up a lot of sod and rolled it up into the bomb bay. That probably saved us. We hit a little something or other and the plane nosed up.

At the moment of impact, Oliver was busily destroying codes and other sensitive material. A large black box came down on him, knocking him out. Deren (the bombardier) and another crewman had taken his place at the radioman’s table, and were trapped as it got crushed in the crash.

Oliver had fallen over onto one of the men at the table as he lost consciousness. When he came to, Deren was struggling to get him off his lap. Oliver used his unauthorized pocket knife to free Deren’s foot from the splintered remains of the table, but the navigator remained trapped. Meanwhile, the pilot and copilot had simply unbuckled their seatbelts and climbed out through a nearby crack that had opened up as the plane rolled up onto the nose turret.

I went to check on another man. He was an older man who kept fighting me and hollering that both of his legs were broke, but the way he was kicking, I knew they weren’t broken. I felt under the table to see how tight he was caught, and it wasn’t real tight. The co-pilot came around and I turned it over to him. He went around to all the first aid kits to find morphine that was supposed to be in each one, but they had all been emptied. He still gave him a shot from one of the empty vials and the navigator, named Bush, calmed right down.

Oliver had been on the verge of knocking Bush out to get him out of the plane and save both their lives. The shock of the crash had affected his mind, and he continued to insist he was in great pain.

The pilots and crew rushed to get their injured comrades out of the plane, assess their injuries, and administer what first aid they could. They worked as quickly as possible because one of the engines was on fire and the remaining fuel in the wing tanks could have exploded at any moment.

The greatest fear of downed airmen was that they would fall into the hands of the Germans, who would either take them as prisoners of war or execute them on the spot. Instead, three local men appeared. After speaking with the crewmen, they went to a nearby house and returned with two jacks to help free the second man at the radio table.

At that time, two groups of resistance fighters were rescuing downed American fliers—at grave risk to themselves. The Germans had instituted a policy of killing 100 Yugoslavs for every German soldier killed, and had been known to wipe out entire villages for hiding Allied airmen, or even on suspicion of doing so.

The anti-communist, anti-fascist Serbian Chetniks hid and aided several hundred fliers, but the pro-Communist Partisans, mostly Croats, rescued the majority of them. They moved the men by way of an “underground railway” to various pick-up points in Yugoslavia, to be transported back to their bases in Italy.

Either way, the experiences of fliers rescued in Yugoslavia were much the same: They were welcomed and aided by strong, sturdy rural village people who hid them in their own homes, haylofts and forests, and fed them from their own meager food supplies. It was fortunate that Dragon Lady had made it across the border and that the crew had fallen into friendly hands. Had they crash-landed in Austria, there would have been little hope that they would have evaded capture.

That night, at the farmhouse where the crew had taken refuge, someone with medical experience examined them. Oliver, with a head injury and with one leg bruised from hip to knee, was in the worst shape.

In the morning, two Yugoslavian political leaders appeared, along with nearly thirty Partisans. The ten crewmen joined the group and began a long journey deep into enemy-held Yugoslavia, all the while avoiding encounters with the Germans. Moving from hiding place to hiding place, the Partisans ferried the crew 380 miles south toward safety at a British mission in the central part of the country.

“Before we got there we had a few interesting experiences,” Oliver recalled. At about one o’clock the next morning, after a few hours of sleep, the crewmen began walking with the group of Partisans down a little valley toward the railroad and a major river.

Oliver, following instructions, squatted in the brush near a German pill box (a hexagonal concrete guard post with small openings through which to shoot). These structures were arranged facing each other, but not close enough to hit each other when guards were shooting. A trip wire was strung through the brush that would alert the men in the pill box to unauthorized intruders, such as Oliver’s group.

A Partisan touched Oliver’s shoulder, and they crept to the trip wire. Partisans on either side of the wire carefully lifted Oliver’s feet one at a time, setting them over the wire.

There were about fifty in the group, including downed airmen and the thirty Partisans. Negotiating trip wires on each side of a railway line, then being shuttled across the wide river in a little boat ten men at a time, took hours, and they were eager to get out of the exposed valley and into the comparative safety of the forest before it got light.

They reached the forest, exhausted, and made themselves as comfortable as possible, finding what shelter they could from the winter wind. Oliver rested fitfully, sleeping a little, moving around a bit, and then taking another nap. His strongest wish was for a handkerchief to keep his neck warm in the bitter wind. After his return to safety he was never again without one. At full daylight they resumed their journey, heading deeper into the mountains.

On the second day they took the navigator, Bush, to an underground hospital because he was still in shock and unable to keep up. Meanwhile, another downed flyer joined the group. The new man had been a tail gunner on a B-17. He told Oliver that the plane had come down “windmilling like a maple leaf,” and had landed softly enough that he simply walked away from it. A few days later, Oliver’s remaining crew plus the new man separated from the larger group, guided by an English-speaking Partisan who had spent time logging in Oregon.

Oliver’s skill and hardiness as a “country boy” served him well as they trekked across rugged terrain. Along the way he witnessed the suffering of the local populace, and also the enduring hostility between the Croatian Partisans and the Serbian Chetniks:

We were headed up into those mountains. There was a river coming down from those mountains…the river was in a pretty deep chasm there. There was another trail following along up the river, but there was another group of Yugoslavs. They had always been fighting each other….The other group was on the other side of the river.

These fellows were really hard up. There weren’t enough shoes, coats, guns to go around. These fellows would run up to the front lines barefoot. There was snow on the ground. There was a partner up there about the same size, and they would take his shoes and gun and then he would run back, leaving blood in the snow.

The trail where they had encountered the Chetniks went down a steep hill and then across a cable bridge. At this point Oliver’s crew caught up to a pack train. One of the horses, in poor condition and carrying a forty-pound load, could not go down the trail onto the bridge—its legs would not hold. They unloaded the horse, and Oliver picked up one of the sacks, carrying it to the bridge, and then going back for the other sack. While he was doing that, the others coaxed the horse onto the bridge.

When Oliver returned with the second sack, they were trying to get the horse across the swaying cable bridge, but it would only go a few steps. They urged the horse forward, but the handler was unable to hold him when, part-way across, the animal reared up, and fell over the cable onto rocks forty feet below. The handler had to shoot the horse.

One night they stayed in a barn, and on another they crowded into a house with several other men. Oliver noted the industry and strength of the local people, as well as certain cultural differences.

One evening, before dark, the group came to a two-story farmhouse with a huge masonry chimney. Their hosts were two middle-aged women and an older man. Oliver, stepping inside, spotted the nearly empty wood box and began cutting firewood, but when the old man started for the barn, Oliver followed him.

A horse stood in a stall with an empty manger. The old man motioned for Oliver to give the horse some hay, but the horse was so close to the side of the stall he couldn’t reach the manger. Seeing this, the old man smacked the horse on the rump and it shifted enough that Oliver could feed it. Oliver noted that the man had asthma and apparently appreciated not having to load the hay.

The next morning, up before everyone else, Oliver heard a noise in the kitchen. It was one of the women fixing breakfast, but the old man was getting ready to wash his face. Oliver watched, amused, as he took a mouthful of water from a dipper, squirted water into his hands, then wiped it on his face, around his head and ears, did it a second time and was done, a real spit bath.

Oliver had resumed his firewood task when he saw one of the other women going into the barn. Preparing to haul manure, she hitched the horse—the one Oliver had fed the night before—to a little low sled called a stonebolt. Oliver grabbed a fork and helped her load manure, but was once again impressed with Yugoslavian strength, as he was barely able to keep up. When that chore was finished, Oliver went in and ate breakfast with the crew.

Another incident where Oliver’s farm-boy stamina proved useful occurred as his group was following a trail that came out of a patch of timber into a meadow. They spotted a man walking in the timber on the far side. Apparently the guide needed to connect with him and receive instructions before they could continue. The guide called to the other man, who was about fifty yards away, but he didn’t hear. Oliver sprinted across the meadow, running wide so as not to startle the man, and got his attention for their guide.

The fliers wore flight boots which included inserts that had electric wires for heat. These boots were designed for sitting for hours in cold airplanes at high altitude, not for hiking across rugged mountain terrain. Oliver was the only member of the crew who had brought his ordinary GI shoes on the flight.

With the best of intentions, the Partisans checked the men’s feet and brought them shoes made of half-tanned leather. Unfortunately, most of them were too small. Deren, in particular, had big feet, so Oliver gave him his shoes and put on a pair of the rough, ill-fitting shoes provided by the Partisans. He modified them to be wearable, but that still meant blisters.

The group continued on for twenty-eight days. By the time they reached the British mission, they were half-starved. Their hosts along the way had heroically and generously shared their own meagre rations, but the men sometimes resorted to eating grass to stretch the food. This poor diet affected Oliver’s digestion for the rest of his life. The men at the mission were also short on supplies, except for hot tea.

After a few days, the crewmen were taken to an airfield after dark. They waited for a plane, but the one that came was not allowed to land. Apparently it was not safe.

The next night they did board a cargo plane, possibly a C-47, for a flight to Bari, Italy. Bari was the headquarters of the British Secret Intelligence Service and the American Office of Strategic Services. Both groups were orchestrating espionage and information gathering from that corner of Europe.

“Going Home” Photo of downed US Airmen being flown from Yugoslavia to Bari, Italy on a C-47.

Before they took off, the men were asked to leave their outer clothes. They flew out stripped to their shorts and wrapped in blankets. Clothing was also in short supply and those remaining behind needed it.

In Bari, back in uniform, they attended a ceremony in which medals were handed out. Oliver was not much impressed:

Deren, when they gave the medals out, said I was the only one who deserved the Distinguished Flying Cross. They said it was just because I had let Deren have my shoes. They didn’t know I had stayed in a burning airplane to get a couple of other fellows loose.

We didn’t take those medals very seriously. When you are saving your own hide, you don’t need a medal for that!

______________________________________________________________________________

1Tom Brokaw, The Greatest Generation (Random House, NY, 1998), xi

2National Museum of the U.S. Air Force. Public Domain

3449th Bomb Group Association: http://449th.org/grottagliefield.ph.

4The Planes of the 449th Bomb Group In World War II (449th Bomb Group Association, 2001). Excerpt via personal communication, 11/2012.

5 Grottaglie and Home, A History of the 449th Bomb Group (Book III) (449th Bomb Group Association, 1989), 115

6 D. William Shepherd, personal communication , November, 2012, from his book, Of Men and Wings, The First 100 Missions of the 449th Bomb Group, 2nd Edition. (Norfield Publishing, Panama City, FL, 1996)

Bibliography

Richard Osborne, World War II Sites in the United States: A Tour Guide and Directory (Indianapolis, IN, Reibel-Roque, 2002), 188

Stephen Ambrose, Citizen Soldiers: The U.S. Army from the Normandy beaches to the bulge to the Surrender of Germany (New York, NY, Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 1997), 294-295

Mark Arnold-Forester, The World at War (London, UK, Pimlico, 2001), 126

Appendix

April 12: Wiener Neustadt, Austria

The deep-penetration, strategic-bombing offensive continued unabated on April 12 as the 449th mounted the maximum effort that had been anticipated for the past several days—the attack on the aircraft factory at Wiener Neustadt. By the end of the day, three of the crews that were at the 0530 morning briefing would be listed on the Group records as MIAs.

The principle target of the day for the 47th Wing was the “WIENER-NEUSTADT AIRCRAFT ASSEMBLY PLANT WERK ONE.” The 5th Wing and the 304th Wing would strike similar aircraft-plant targets at Fishamend and Bad Voslau. While these three wings were concentrating on the aircraft production facilities in Austria, the 49th and 55th Wings would strike the enemy airdrome at Zagreb, Yugoslavia.

For its part in the day’s operations, the 47th Wing would send all four groups to Wiener-Neustadt in two waves. The lead wave of the 376th and 98th Groups was loaded with 500-pound, GP bombs. The second wave of the 450th and 449th was loaded with 100-pound, clustered, fragmentation bombs.

The Luftwaffe was estimated to be capable of sending as many as 300 fighters to oppose the attack on Wiener Neustadt. To help deal with this enemy fighter force, escort on the route to the target would be provided by one group of Lightnings. At the IP (Initial Point), [i.e. The starting point for a bombing run.] the 449th formation would be met by a group of Thunderbolts which would provide cover over the target and along the route back.

Photographic reconnaissance conducted on February 28 and March 8 showed that some eighty-three heavy guns were located around the target area. The lead aircraft in each attack unit loaded three cartons of “window”, a radar countermeasure also known as “chaff”, that was to be dispensed from the IP to the target in an effort to confuse any radar-directed anti-aircraft batteries. [“Window” often consisted of shredded tinfoil.]

Swan’s crew, in ship #55, led the 449th combat formation into the air at 0747 hours. By 0830, the Group had thirty-six B-24s airborne and headed for rendezvous with the other three groups. Shortly after making the rendezvous, ship #42 turned back because of “a very sick gunner.” The formation headed northward across the Adriatic. A malfunctioning supercharger forced ship #27 to drop out of the formation and make an early return before reaching the Yugoslavian coast.

From the coast of Yugoslavia, the planned route would have taken the 449th just west of Mostar. For some unexplained reason the 449th formation drifted well to the right of the briefed course. This variation in course almost resulted in disaster for Brown’s crew aboard ship #33 when the formation came within range of the flak defenses of Mostar. The “moderate to intense, accurate, and heavy” flak ruptured one of the gas cells in the left wing of ship #33, and severed the gas lines between the booster pumps. It took a good ten minutes for Lt. Brown and his crew to realize they had no choice but to drop out of formation and head back to Grottaglie.

The P-38 escorts joined the formation at 1105 hours to take the bombers to the IP. As the formation approached the IP, the P-38s handed the escort job over to the arriving P-47s. Flak bursts began to appear in the sky ahead. As bomb-bay doors opened, the waist gunners in the lead aircraft of each unit began to dispense window, the radar countermeasure. With “moderate to intense” flak bursting around them, the thirty-three aircraft flew over the target, and dropped 52.05 tons of 100-pound, GP bombs at1207 hours from 22,000 to 24,600 feet.

The landing ground and the airdrome were observed to be well covered by bomb bursts. Dense smoke covered the whole target area with “columns of it rising to 10,000 feet.” Flames and at least one large secondary explosion were observed as the hangars just to the right of the aiming point were squarely hit by the bomb pattern. Coming off the target, the formation rallied to the left. While one group of enemy fighters decoyed the escorts away from the bombers, another group succeeded in closing with the 449th formation. Three 449th B-24s fell victim to the aggressive enemy fighter attacks. Ship #10 [the Dragon Lady], manned by Olson’s crew flying in position ‘A-1-5’, “started losing altitude”—probably due to flak damage—as the formation made the rally. The enemy fighters immediately pounced upon the stricken aircraft which had the #4 engine feathered and one wing covered with oil. Ship #10 was “last seen making for clouds just beyond target, time 1207 hours.”

D. William Shepherd, personal communication , November, 2012, from his book, Of Men and Wings, The First 100 Missions of the 449th Bomb Group, 2nd Edition. (Norfield Publishing, Panama City, FL, 1996)

Narrative Report No. 43 Date: 12 April 1944. 449th Bomb Group Mission Report.

The average estimate of enemy fighter planes seen was 25 to 30 ME-109s and FW-190s, the number of the latter varying from 2 to 6 planes. Most of our aircraft reported attacks by 6 to 10 fighters. Six of our aircraft, however, reported attacks by 15 to as many as 30 fighters.

All but one of the ships reporting the larger number of attackers stated the attacks were en mass towards the nose, one reporting two waves of 12 to 15 each. Several reported that decoys drew off the P-38 escorts and then mass attacks abreast were made out of the sun from 12 to 2 o’clock. Those reporting the smaller number of planes likewise reported many of the attacks towards the nose from 10 to 1 o’clock with the attackers coming in abreast. Most of the other of these smaller attacks were at the tail from 6 o’clock level. Practically all of the attacks were very aggressive and were pressed right thru the formation. The formation was under attack for about 15 to 30 minutes from the time our aircraft started their rally.

CHAPTER 3 – Transition

Oliver and the rest of the crew of Dragon Lady waited in Bari for a backhaul on an empty C-47 freight plane. They had not yet completed the required number of missions to finish their tour of duty, but the military reassigned them on account of their twenty-eight days in Yugoslavia.

After a couple of days they caught a flight to Casablanca. Then they continued on to bases in Newfoundland, New York City, and Salt Lake City, where they went their separate ways.

Meanwhile Ed and Pansy, Oliver’s parents, had moved to Nampa, Idaho, a town of about 12,000 some twenty miles west of Boise, after Ed had quit his sawmill job in Snoqualmie, Washington. Ed purchased a truck and established a trash-hauling route in Nampa, and also hauled and sold firewood from a sawmill in the nearby town of Emmett. They endured a very difficult and stressful April while Oliver was missing in action in April of 1944.

By around the first of June 1944 Oliver had been assigned to a base in Galveston, Texas. Initially he served as an instructor, most likely once again in radio operations, but soon the military sent him for a short course to learn how to operate the radio in a B-29. Meanwhile the defense plants continued to develop and turn out improved aircraft at a steady clip, and the B-32 soon superseded the B-29.

Oliver never flew a training flight in the B-29, but he did qualify for service aboard the B-32, a new low-altitude bomber that flew below radar. His time in Galveston was short, although he did find time to swim at the beach and get stung by a sting ray, an injury that was very painful and took “a long time” to heal.

While the war was stressful and difficult for everyone, the anxiety must have been enormous for a family with four sons of military age. Oliver had been called up first, in 1942. Keith had asthma and was exempt. The next brother, Phillip, enlisted in February, 1943, and was a co-pilot on B-17s flying out of England. He only made a few flights before the end of the war, and returned home safely.

Carol enlisted in March, 1944 at the age of 18, and was assigned to the 78th Infantry Division, 309th Infantry Regiment. The unit left for Europe in October and arrived in Germany in mid-December, just in time for the Battle of the Bulge—the last major Nazi offensive against the Allies in World War II.

The division breached the Siegfried Line1 near the Hürtgen Forest in late December and continued to fight their way into the heart of Germany, capturing the huge Schwammenauel Dam and then—famously— The Lundendorff railroad bridge at Remagen, allowing the Allies to cross the Rhine River, an unexpected advantage since the Germans were blowing up all the bridges across the Rhine. Books, and even a movie, have been written about this event, which was a great boost to the Allied effort to win the war. Thus, Oliver’s brother’s Division, the 78th, became the first infantry division to cross the Rhine—an achievement that signaled the final stage in the defeat of the Nazis. The Remagen Bridge was captured by the Americans on March 7, 1945. Carol was killed two days later, on March 9, when the Germans began a fierce but ultimately unsuccessful attempt to retake the bridge. He is buried in Belgium.2

By that time Oliver had been assigned to Mountain Home Air Force Base. Since the base was only sixty miles from Nampa, he was able to spend his weekends with his parents and his siblings Keith, Jessie and Dell. (Phillip was still in England.)

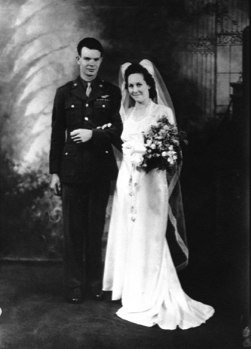

Keith introduced Oliver to his circle of friends, among them a young woman by the name of Lorene Flynn. She also had family in the area, and was studying elementary education at Northwest Nazarene College, a local private school.

Like many of his fellow returning soldiers, Oliver married right away. He and Lorene—all his life he would call her Rene (pronounced “REE-Nee”)—married on June 14, 1945, while he was still in the service. They bought a small trailer house, parked it on a big farm off-base, and began their married life.

Photo from the Cameron family collection.

The B-32, for which Oliver had trained, flew its first combat mission a couple of weeks later. However, the atomic attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki led to Japan’s unconditional surrender on August 15, 1945, before Oliver could again see combat. The war was winding down. Oliver spent his final days in the service as a flight radio instructor.

The military began releasing soldiers on a point system that favored those who had served overseas the longest. In spite of the fact that Oliver’s overseas tour had been very intense, he had only been abroad for six months. As a result, he had to wait longer than some others.

Never one to sit still, he quickly found work. One of his first off-base jobs during this time was on the South Fork of the Boise River, about 20 miles northeast of Mountain Home, where the Anderson Ranch Dam was under construction. On his days off, Oliver would drive out to the site and help clear sagebrush and rocks.

He finally received his discharge on October 18, 1945. After collecting $250 in separation pay, Oliver was free—finally—to return to civilian life.

He and millions of other newly released soldiers then began the process of adjusting to peacetime. Horrific wartime experiences fueled their drive and passion to put the nightmares behind them and move forward with building homes, families, and careers. As Tom Brokaw noted in The Greatest Generation, this group of young men and women would become one of the most innovative and productive in American history.

The United States made efforts to honor and assist returning veterans. Many of them took advantage of The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, commonly known as the GI Bill of Rights, to go to college—an opportunity undreamed of before the war. The government also offered GI Loans for business startups or home purchases.

Oliver, the independent self-starter who considered himself done with formal education when he graduated from high school, declined the educational benefits of the GI Bill. As a child of the Great Depression, he also avoided excessive debt. Even when it became the norm to borrow for a new house or car, he stayed true to his principles.

Although it was a great relief and a source of hope to get back to “real life” and to be among friends and family after the war, Oliver found that it was hard to find work in western Idaho. He and Rene moved from Mountain Home to Nampa, where he picked up whatever temporary jobs he could find, such as dismantling old railroad cars. While he had this job in the railroad yard, he and Rene lived in a rooming house on the north side of Nampa.

He did tap into his GI benefits in order to purchase a former military truck. He cut the chassis just ahead of the transfer case, lengthened the frame by 34 inches, and built wooden bunks—metal frames for holding a load—on the bed for hauling logs.

He started getting jobs, but not everything went as planned.

“That’s when I got caught in the avalanche and come pretty near getting squashed.”

It was spring; the snow on the ground was thawing, creating runoff and making the steep roads in the Idaho mountains nearly impassable. Oliver got a job hauling logs to a sawmill in the mountains outside of Idaho City. The trucks had to be pulled up high on the mountain to the loading site with a caterpillar tractor due to the poor condition of the switchback roads, and driven back down to the sawmill.

Oliver had just made new bunks and had cables attached to hold up the side stakes of the bunks. The first layer of logs—the deck load—needed to be tight, but the loader put in a log that didn’t fit, so they dropped another log onto it to force it in place, which broke the cable clamp loose from the bunk stake. To compensate for that, and to secure the load, Oliver ran a chain from the trailer hitch around the outside log, effectively tying the load to the truck, a big mistake.