CHALLENGES

Bears are one of the hazards of living as Oliver did. Image by Heidi Dammann

Living the subsistence lifestyle presents physical and psychological challenges. Oliver discusses these in the next four essays.

DANGERS

Animals

A gun is vital for protection from animal dangers. I used to carry a .44 Magnum revolver with a 10-inch barrel. I could protect myself pretty well with that, but I got rid of it because I was going to damage my hearing if I ever had to shoot it without ear protection.

Now I have a rifle. I took a .65 Carcano Italian military carbine and cut the stock down to a skeleton. I filed it down toward the barrel where it tapers—not next to the cartridge chamber.

That gun, with six rounds of ammo in it, now weighs less than five pounds. I carry it for self-protection, mainly against bears. I once shot a large, mature black bear with that little gun. The animal only went about 40 feet before it died.

Rabid animals are another danger. There’s no guarantee you won’t be up against one when you’re out in the wilds. I’ve had to kill rabid foxes.

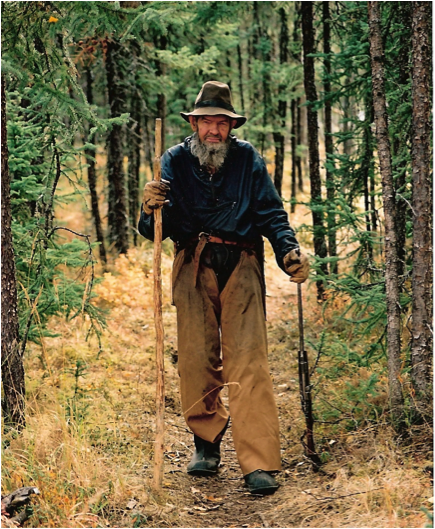

Oliver with walking stick and rifle.

Image by Devta Khalsa

I’ve also had a couple of run-ins with moose. When a moose has its ears pointed toward you and its hairs up, you need to give it plenty of room. I’d just back off and go another way. I’ve never had to shoot an aggressive one.

Snow blindness

Snow blindness or photokeratitis is when the eyes themselves get exposed to ultraviolet light and get a kind of sunburn. The symptoms come on a few hours after exposure. I have experienced this on a few painful occasions. It feels like you have some kind of grit in your eyes. They burn, and you can’t keep them open. I’ve had flash burns from arc welding, too, and it’s a similar thing, where the eyes themselves are exposed to too much ultraviolet light. Protective eyewear is the way to prevent both kinds of eye damage.

One time I was out and didn’t have dark glasses or snow goggles with me. I was on a trail behind my place, in the trees, so I didn’t think I needed them. But when I came close to the lake, I was out in the open. I noticed some tearing in my eyes. I doubled over my neckerchief made of thin cotton and draped it over my head, under my hat. I could see through it, and that was enough to keep my eyes from getting any worse. Even with that, it was several days before my eyes were comfortable again, even in ordinary light. When I went out for the next several days, I wore sunglasses that were so dark I could hardly see through them.

Breaking through the ice

Breaking through the ice is a real danger. Don’t do it!

I never broke through seriously, but I once broke through overflow, sinking down above my high mukluks. They were fastened snugly, so the only thing that got wet was my pants above the knees. [Overflow is waterlogged snow on top of ice, concealed by a layer of dry, insulating snow. It often occurs where groundwater emerges from a side slough. It’s a real bummer when the crust breaks up and your dogsled settles into the slush. You may have to carry your load to firmer snow before you can get your team and sled to safety. It can be worse if you’re driving a snowmobile.]

My breaking through the overflow could have been serious, because it was about ten below zero, but I was only a mile from a tent and a stove. I moved fast and got warm pretty quick.

You can usually tell where there might be overflow if you carry a stick and thump it on snow ahead of you. The stick should be long enough so that if you fall through a hole in the ice, it will span the hole to support you as you get out. The main trouble then would be if you had no way to make a fire after, to get warm enough again.

Cold

One time I was hauling some caribou that I’d cached on high ground in the low mountains north of Shungnak. The days were short and cold.

I went by myself on a trail that wound up a creek on the back side of the mountain; it took longer but wasn’t as steep as going up the face.

My meat pile was close to where the slope of the mountain dropped off on the face. It was getting late and I wanted to get home quickly, so I tied a carcass on each side of the sled and one behind before starting directly down the steep face.

We came off that hill like an avalanche. I was riding the brake to keep the sled from overrunning the dogs, but in the deep loose snow, that didn’t help much. I worried what would happen when we got to the deep, soft snow at the bottom of the mountain, but I managed to get the sled stopped where the slope abruptly flattened. I untangled the dogs and put on my snowshoes to pack down the snow to reach the main trail.

At first there was a gradual slope toward the river, but when we got onto the flat, the terrain was up and down. The sled didn’t slide easily in that cold, and the upslopes were steep. The dogs couldn’t pull the sled and me, too, so I had to run behind and push the sled to help them and then jump back on and ride until the next rise.

With this exertion, I got overheated and worked up a sweat, so I didn’t realize that it was 65-below on the river. I had a good ruff that held a little pocket of warm air in front of my face, but I had pushed the hood back on my head to lift my parka for ventilation. When I got home, my lungs were haywire. I had frosted my trachea. That was almost fifty years ago, and I still have problems when I’m outside breathing deeply in the cold.

Your breath hisses when the temperature gets down to 45 below 0. If you purse your lips and blow out, it sounds like a little jet engine. It’s an interesting self-thermometer.

Hearing loss from firearms

Part of my hearing loss was due to a greenhorn [a novice] who went out hunting with me. He had a 7 mm Remington Magnum. I was using a smaller gun. I’d shot a big caribou. It was staggering, and I was waiting for it to go down. I didn’t want to use another bullet and ruin more meat for just a minute or two of difference. The greenhorn got impatient. He was standing behind me, to one side, and he shot that cannon of his. That’s why I have bum hearing in one ear. I’m still angry about that.

* * *

The truth is, in rural Alaska there’s danger in the air. If you’re careless, you’re going to be in trouble. Sometimes you can get away with it, but it’s better not to test nature.

When you’re out here, you need to be thinking about security all the time, in everything you do. After you’ve been at this homesteading thing for a few years, it’s just second nature to be alert to danger, even when you’re exhausted.

LONELINESS

During my life up here in Alaska, there were several stretches when I didn’t see anyone for months, especially during breakup or freeze-up. More often I was alone for days. I had these long periods of no contact with people until I started using CB radios.

I have lived alone for much of my later life, but ultimately we are social beings. There is always a certain need for human companionship, but if you don’t have it, you don’t have it.

There are lots of people in that kind of fix. Even with people around, they’re still very lonesome. I myself don’t notice it any worse when I’m by myself than I do when I’m talking with somebody.

Actually, loneliness is more of a problem for me when I’m in town and there are people around, but I don’t know them. That kind of situation makes me aware of my isolation more than being on my own.

Dogs provide both labor and companionship. Here Jan Cabanis enjoys her canine friends. Image by Bob or Dorene Schiro

When I’m alone, I talk with the dog. It’s amazing how sensitive some dogs are to feelings, and to speech.

I usually am not talkative in general. Most people want somebody to talk to, but I’d rather just listen. Quite often I don’t have too much in common with most of the people I’m around, even those people out in the Bush.

Cabin fever

I have never had cabin fever, but it can be a problem for some people. There are times that I get pretty restless if I can’t get out and spend time outside, but I never get any kind of desperate feeling. I always have too much going on inside, as well as chores and work that need to be done.

That said, cabin fever can be more subtle than most people realize. It’s not a specific thing with specific symptoms to go with it—it can be different things with different people.

Quite often it’s a matter of personalities. Some people can handle being cooped up a lot more than others. Others want more elbow room, or they get to feeling frustrated or claustrophobic.

Up here, we live in smaller spaces. If you are living as a family, I feel it’s very important that each individual have a location that’s his, where he can feel secure that anything he leaves there will be there when he comes back.

I read a humor piece in the Anchorage newspaper about two men who got dropped off for a week to hunt caribou in the Lake Clark area. They got their animals right away, but their plane wasn’t scheduled to pick them up until the end of the week. The weather turned bad, and they were confined in a small tent for several days.

The humor was about how they got on each other’s nerves. At one point, one of them got irritated when he caught the other reading the label on his tube of foot cream!

Once I got so desperate for reading material that I walked up to my neighbor’s and asked him for something I could read. He gave me the little Kreps book on woodcraft [E.H. Kreps. Woodcraft (Columbus: A.R. Harding, 1978), 47-50]. I nearly wore it out and could quote just about any page. I bought Pete a new copy.

I think the remote lifestyle is probably easier on men than it is on women. It takes more planning and deliberate effort to make sure that women get outside. Men get out naturally with hunting and getting firewood, but it’s hard for women to get out, especially if they are looking after small children.

I remember one couple. The woman had no way to take the kids and get out. They only had one dog, and it wasn’t trained. They didn’t have a sled, so she could hardly get out of the yard.

When I met them, I made a sled and harness for their dog. It made all the difference in the world. Even if there was no snow on the ground, she could go down to the lake or go out picking berries. With the addition of a couple of dogs, she soon had the beginnings of a team. Those dogs could pull that sled most anyplace, loaded up with the kids and their gear.

A man named Dick Griffith was well known for taking epic solo walking trips in northern Alaska—from Barrow to Anaktuvuk, from Anaktuvuk to Ambler, and so on.

He told me about a time when he unexpectedly came upon a trail somewhere in the Brooks Range. He followed it to a cabin, where he found a lady who was living by herself while her husband was away for a stretch of wage employment. He said that she talked non-stop.

When you’re with somebody who is the primary sharer of your life, you get to the place where there’s not a whole lot to discuss. Then, when somebody new comes along with a good ear, you’re hungry to talk.

I think that’s a very human thing. Alaska provides a situation where the loneliness is made worse—people can get almost starving to talk.

For some reason I’m not afflicted that way. That’s a good thing, because I’m out there by myself so much.

Families

When children grow up in an environment that both expects and allows them to be self-sufficient, they become adults early. They can be trusted to be out and taking care of themselves. Children who grow up in different setting don’t have that advantage.

I’ve noticed that difference between the Inupiaq children and my children. My kids were raised to be very independent, early on. The Inupiaqs have a tradition of interdependence in their close-knit communities. When the Inupiaq kids would come over to play with my kids, mine would seem to have a lot more initiative or ability to forge out on their own. It may have just been bias on my part, but I consciously tried to encourage my children to be individuals. There’s a balance you have to find with that. As far as the Inupiaq culture goes, the interdependence and closeness that they have fills a definite purpose—though probably more so in the past than it does now. Under the circumstances of their traditional lifestyle, that tendency to be a close part of the family or the extended family was something that helped them to learn more than if they were more independent. But I think for my own children, being independent was vital for them to live up here.

Oliver’s family. From left: daughter Dorene, son Ricky, son Gary, Oliver, and wife Lorene. Image from the Cameron family collection

PRIORITIES

My advice for people who are new to making a remote life in the woods is this: it’s important to stay connected. Don’t cut your lifeline. Give this lifestyle a try. You’ll learn a lot, but you’d better keep something to return to if you don’t enjoy it.

There were a lot of people who tried to make it out near my homesite at the lake but had to give up. One young couple would have failed if I hadn’t been there to guide them. Duane and Rena Ose and I were the only ones who really made it out there by the lake.

Aperson who’s had a little experience in subsistence living can live all winter in a tent, but that’s not for somebody who’s never done anything like that before. One couple in Ambler—let’s call them Bernard and Lea [not their real names]—were real greenhorns.

In Ambler, Bernard and Lea were using a house pit between Dan and Joyce Denslow’s, toward the village. [There were several shallow, moss-covered pits with raised rims in the Ambler area, the remains of centuries-old Inupiaq semi-subterranean dwellings.] My wife, Lorene, and my younger son, Gary, were leaving the area, and I asked Gary if he wanted me to sell Bernard and Lea his tools if I got a chance. He did, so I sold them his axe and his bow saw.

I also gave them a few things—an old tent and a fish net—but they didn’t know how to make good use of them. They lost a lot of fish because they didn’t know how to work with the net.

They improved the house so they could live in it, and they built a cache, but was not set firmly in the ground. It leaned too much. They tied a rope to it to brace it, but mice and squirrels kept running up the rope and getting inside, ruining their stores.

I went over there one day, and Bernard wanted to make tea for me, but there was no wood cut for the fire, and it had been raining. They had some wood in the yard and it needed to be cut. He went out and started whacking away.

Watching him, I realized his axe had become more of a hammer, so I asked if he wanted to borrow a file.

“What for?” he asked.

“To touch up the blade and sharpen it,” I replied.

“Oh. I thought I had to buy a new one,” he said.

Bernard and Lea were intelligent people, but they came from a culture where instead of repairing something, they were always buying a new one. This situation they were in out here was too different from that—there weren’t any axe bits to buy. So where to start with somebody like that when you want to talk about how to live out here? Whatever you say, they probably won’t understand.

I’m thankful I grew up the way I did, in the era I did. I learned skills that other people nowadays don’t get a chance to learn. But those skills—blacksmithing, handcrafts, building—allowed me to succeed later on in life.

One of the biggest problems people must overcome out here is prioritizing their time. It can seem that you’ve got plenty of time on the clock, but it takes a long while to get your wood in and everything set for winter. If you put off tough chores, they’re going to take more time when you finally get around to them.

Starting at a new place in summertime, people usually take time to explore before deciding what and where they want to build. Meanwhile they get wrapped up in fun activities—going swimming or exploring or visiting. The days are long, but amazingly soon they turn short again. If you are going to make it at a new homesite, it’s important to get your house finished, get some wood cut ahead of winter, get supplies cached, and so forth.

People who know about subsistence living in your area are a valuable resource. One of the best things about having experienced neighbors is that they’ll have an idea of what you need to do—and don’t need to do— in the summertime to prepare for winter.

One year, a fellow who had a run-down place in Ambler was trying to fix that place up. I had let him stay in my son Gary’s house, the original house I’d built, behind Pete MacManus’s place, just upriver from Ambler, while he was working on his home.

Instead of preparing for winter, he kept busy writing love letters to his girlfriend and fixing up an old net I’d salvaged from the river and given to him. It was usable, but he was very particular about mending it until it was just like new. He didn’t pay attention to how summer was passing, nor that the net really didn’t need any more mending. I told him that even if the net did have a few holes, it would still catch all the fish he’d need for winter. But he wasn’t satisfied. I don’t remember how he was getting the fish he was eating. Sometimes I gave him fish.

One day I went over there, and he showed me the neat job he’d done on that net. I got disgusted and blew my top a bit. I told him, “You’d better get your act together. The time is almost past for using the net. The caribou are going to come pretty soon, and you’ll still be fiddling around here. You haven’t got your place ready, and you’ve used the wood I’ve gotten for you and stacked here.”

That was something of a shock, I guess. But he must have understood it, because he finally got going. He got the net into the water, and started picking up wood along the river. I don’t know what he used for a boat—maybe he borrowed mine.

Shortly after that the caribou came. He didn’t know what to do, so I took him out to get some. I already had all the meat I wanted, so we got two or three for him.

All in all, he didn’t manage his priorities. I think that’s an important thing to mention, because in our culture there are a lot of people who don’t set priorities for themselves. It’s done for them by their job or their school.

Without priorities, people waste time and energy, especially in a money economy where it is easy to buy everything you need to survive. Living like that is a good way to fail when you go out into the woods.

What I’m trying to say is this: You need to make your plans to give you the best break you can get. Don’t expect too much when you get out in the woods.

If you can arrange it, get out to a new homesite shortly after the snow is off the ground and the lakes have opened. That way, you’ll have all summer to work. A person with some experience could go out there earlier in the spring and get by even if the lakes are still frozen and there’s snow on the ground. But newcomers without experience will fail.

One year I had hoped to go to the lake early, but shortly before I was ready to move I had to go to the hospital. That took some time, and I figured I wouldn’t have long enough if I didn’t arrive at the lake by the middle of August. It was a little later than that when I finally got to the lake. I still wasn’t in the best of health, and I wasn’t at all sure I could make it. But I did. I’ve had plenty of experience, and I was also lucky that others were there and I could hire a little help.

Obviously it’s important to know how to set priorities, especially if you’re limited on time.

Dan Denslow, a neighbor, once asked me how I seemed to know whenever he and his wife Joyce might need help. I explained that it was because they hadn’t been up there long enough to know what was coming, nor how soon. I could see that they weren’t getting everything done, that they weren’t going to finish everything they needed to do before winter, and so I’d go over and help them.

Dan was exaggerating to some extent; I didn’t always know when they needed help. But often I did because I’d been in the area long enough to see they weren’t using their time wisely. I knew what it took to succeed.

It takes a while to learn priorities.

SURVIVAL

Survival kits

I am seldom far from home without a day pack. One of the things I carry in that day pack is some birch bark for starting fires. I also have some light rope, some pemmican, a couple of tea bags, and a small cook kit—or at least a can with a handle on it in which I can boil water to make tea.

Depending on what I’m doing and my reasons for going out, there is usually an assortment of knives in my kit, each in its holster. When I’m butchering caribou, I don’t want to have to stop to clean and sharpen my knife, so I keep several knives sharp and ready.

When I do sharpen while I’m out, I can strop the knife on the back of another knife or the edge of an axe or a kettle. I can only do that a few times before I have to bring its edge back with a whetstone, so I carry a diamond stone to use as a sharpening steel when needed.

Crockery of any kind also makes a good hone in a pinch. The bottom of a bowl or mush dish often has a place where there is no glaze on the bottom. That’s a good place to touch up your knife. Even a broken plate edge works— on the edge the abrasive clay is exposed.

One thing I always have in my day pack is a pair of dry gloves. Those can come in real handy.

I have another little survival kit that I carry in my hip pocket. It has a Marble’s screw-together match safe and also a plastic match safe with a compass built into the top. [“Marbles” is a company that makes knives and hatchets and other items for campers.]

One of Oliver’s many easy-to-carry tool kits. Image from the Dammann collection

In that hip kit, I usually also carry my sewing kit with extra nylon thread wound on a small net needle. It’s hard to do anything with fine thread if you don’t have it on a net needle or something similar. Winding the thread around the net needle let’s me carry a lot of line without it taking up much space.

Thread is really useful in a variety of situations. If you have to build a shelter, you can use it to tie a tarp or hold some sticks together.

Oliver sets out with his various kits and tools strapped to his belt. Image by Heidi Dammann

Water

Very seldom do I carry water. It’s heavy. Around home I know where I can find water, but I usually do carry a strainer.

One time I was out with my dog. I was in a swampy area, and the ground was soft and the moss deep. I stopped to have a bite to eat. Pretty soon the dog started sniffing around some moose prints, stuck his nose down in, and started drinking.

In a place like that, a fellow can soon have a hole with some water in it. It will taste like tundra tea [water that contains and is stained by natural compounds called tannins], but won’t have any Giardia in it. I would drink some of that rather than lake water where I knew there were beavers and other animals [Giardia contaminates water from the feces of various animals].

Plant tissues contain compounds called tannins that are released into water as their leaves, stems and other tissues decay, imparting a reddish tea color as shown in this stream in Pennsylvania. (Image credit 46)

I usually carry a metal cup. If there’s a little drip or trickle of water anywhere, I can dip it with the cup and put it in my kettle. Boiling water after filtering or straining it kills most problematic pathogens.

I carry paper towels for wiping my hands when I’m out. I have used grass, but grass, especially when it’s dry, is pretty scratchy. If you’ve been working with game and your hands are bloody, when you wipe them with grass you can scratch the skin and cause a serious infection.

Getting Oriented

One of the first things I do before going into an area is to fix in my mind the lakes and the mountains that I can see. Then I always have that visual compass with me, in addition to an actual compass that can show me the directions.

When you’re out among repetitive little knolls all covered with poplar, and the sky is overcast and it’s getting dark, you’d better have a good idea where you are so that you know where to go.

One time I was out hunting small game—rabbits or birds. It was among a lot of poplars in a wooded area. I had a big picture sense of where I was, but in the smaller scale among the poplars, I wasn’t so sure. I started to walk out of the trees, and pretty quickly, I came across somebody’s tracks—you can guess whose they were: mine! I have a tendency to walk in circles. One leg is shorter than the other.

If you’re out—especially alone—when the wind is howling and the air is full of snow, it’s hard to keep yourself oriented or even see across the river. It can be a big problem.

There have been a few times when I’ve had experiences like that, when I’ve overextended myself and wasn’t really prepared to stay out overnight. It’s a good idea to have some idea what to do in those situations, an emergency plan.

If you can find shelter and you’ve got a sled, a sled cover, and a caribou skin, you’ve got it made. You can use these for shelter. But if you’re walking and it gets late and you’re just carrying a rifle, it’s tough. It can be easy to get disoriented—especially if you’re following up on some crippled animals.

As long as you’re close to the river or you can hear the village dogs, or the weather allows you to see the stars or the mountains, you’re OK. But there are times when you don’t have any of those things to go by. That’s when a compass is important.

There is a common bit of advice given to greenhorns without much experience: if you’re lost, stay put until somebody comes for you. If you’ve got ammunition, after a reasonable amount of time, fire three shots. That’s the usual call for help. Wait a little while and fire three more shots, hoping that you’ll hear a couple of shots in response.

If you stop and build a fire and eat some lunch, that refreshment sometimes makes a lot of difference in your perspective. You can then figure out a reasonable course to take. But if it happens to be late in the day, you’re going to have to do whatever you can to make yourself comfortable and secure for the night.

I’ve only had to do that once or twice. I was never without a piece of canvas or some of those flimsy space blankets that fold into a bundle the size of a pack of cigarettes. They were part of my emergency kit. [A space blanket is a low-weight, low-bulk blanket made of heat-reflective plastic sheeting. It is designed to reduce the heat loss in a person’s body due to thermal radiation, water evaporation, or convection.]

The reflective foil in a space blanket can direct heat back to a person’s body or deflect incoming sunlight. It packs down to a very small size. (Image credit 47)

One night it was cold and I didn’t have enough stuff with me to keep warm. Before it got too dark, I cut a pile of firewood so I could build a fire. During the night, I would doze off, and when I’d get chilly, I’d fix up the fire. I made it through, but that was because I had the skills I needed to do so.

You can build a long fire, the length of your body, to heat the ground. Once the fire dies down, rake the ashes off to one side, put some branches on that hot ground, and lie down to get yourself warm. They say you can be quite warm and comfortable that way.

I’ve never tried it, but I’ve talked to a couple of fellows who have done it. They said it worked out very well, but one of them had also heated some rocks that he placed in that bed. During the night, when he was twisting around and trying to get comfortable, he got too close to one of those rocks, and it was uncomfortably hot.

Once when I got caught out, it was late in the day. I was out looking for a pile of caribou meat down toward Hunt River. I hadn’t wanted to go out again late in the day, but some hunters from Kiana had left some animals there. I had gotten some meat of my own and taken it home, but I was going to go back to get their abandoned carcasses to use as dog food.

I didn’t find it right away. The weather was bad, so I went into the woods and found a big bushy spruce tree. I scraped away the snow, broke off a few branches, put them down, and put my sled on the branches. Of course the sled was pretty narrow to sleep in, but I had my sleeping bag and I pulled the sled cover over me. Being sheltered from the wind, I was comfortable.

I think those kind of experiences give you a lot of humility as far as dealing with the outdoors. Don’t get cocky with Nature.