The wolves were howling off to the north again. It was late February, 1991, and 69-year-old Oliver Cameron could hear them through the log walls of his dwelling, a 10 X 12-foot structure dug about four feet into the ground, the walls built up another three feet with stacked logs. It was a snug, warm shelter, with just room enough for his bed, a workbench and the stove. The walls were hung with tools, handmade by Oliver. The floor was covered with wood chips and sawdust.

A pilot friend, Jack Hadden, had flown over that morning to check on the two isolated home sites— Oliver’s plus Dennis and Jill Hannan’s a half mile distant— and reported via radio an old wolf had been hanging around the nearest town, Minchumina, killing puppies. No one had an opportunity to shoot it yet. While Oliver duly reported these wolf activities in a letter to his daughter, Dorene, they did not alarm him. Just now evening chores were his main focus: he needed to get in more snow to melt for water, cut up the firewood he and his dog, Pack, had gotten in the day before, and to bring in another piece of frozen moose meat to cut up for kauk and to dry behind the stove he had fashioned from a five-gallon metal can. The weather was warming up – it might reach 30° in a day or two – so the meat would be soft enough to work without warming in the house first.

His foot was better. The previous fall, while hunting, he had injured his foot and had to hobble about with a cane. He was starting to recover when his feet got tangled with the cane and he fell, severely straining his leg muscle and fracturing a rib. Regular soaking of his foot, which tended to swell if he did too much, and taking it easy over the winter had improved things, but he still was not walking far. A bit later in the afternoon he planned to take a little stroll—not more than a mile, yet—and probably end his jaunt at his neighbor’s house. While Jill’s husband Dennis was away working to earn some cash to tide them over the year, Oliver kept a protective watch over her and their two young boys. He had spent some time babysitting just that morning so she could get a much needed run with her dogs and sled. She too, was recovering from back and hip problems caused by an old ankle injury and exacerbated by too much lifting.

He and the boys were working on a mountain banjo, fashioned from pieces Oliver had cut from spare bits of wood he had. Now that the banjo was starting to take shape, the boys were getting excited, and all of them were curious to see how it sounded when finished.

At 2:00 Oliver set aside his letter writing and turned on the radio to listen to news of “Desert Storm,” just days from a cease-fire. Oliver might be isolated, 30 miles from the nearest airstrip and 150 miles from the nearest city, Fairbanks, but he kept as informed and up-to-date as possible. Mail was flown in on a frequent if somewhat erratic schedule. He had radio contact with the handful of neighbors in the vicinity, and listened to the news. Even so, it was a very isolated existence.

How—and more importantly, why—did a nearly 70-year-old man in mediocre health come to be living alone in the unpopulated interior of Alaska? Oliver’s own words sum up his mindset:

I am not much a part of our culture and don’t practice the careless ways they have adopted to any great extent. I have to do what is necessary to survive with the means of the energy, perspective, and materials available. – Oliver Cameron

This is his conviction in his later years, but how did he arrive at this place, both geographically and spiritually? What is Oliver’s story?

Since we must begin Oliver’s story somewhere, let us begin with a young couple born in the British Isles. James Cameron was born in the parish of Ardnamurchan, Argyll, Scotland in 1815. Ardnamurchan is a 50-square-mile peninsula in the Scottish highlands, noted for its beautiful, wild, undisturbed nature. Even now the population is sparse, consisting mostly of fishing villages and sheep crofts. James left this rural highland area to travel to the United States in1852, sailing from Glasgow, Scotland, to New York.

Annie Bennett was born in Newcastle Upon Tyne, England in July of 1830. She came to the United States as a teenage girl and married James Cameron in Oshkosh, Wisconsin around 1860.

Another tributary to Oliver’s life involves an area that later became the State of Montana. The year 1862 was a pivotal year both for the land that the United States had acquired in the Louisiana Purchase and for the Cameron family. In that year, while Montana was still part of an area known as the Idaho Territory, President Lincoln signed the Free Homestead Act, opening much of the Midwest and West for settlement. The Act encouraged westward migration and the settlement and farming of vast tracts of land in the United States. It allowed those with grit and determination an opportunity to acquire their own homes, farms and ranches, and would be a major influence in the Cameron family for three generations.

Signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln on May 20th of that year, the Act provided settlers 160 acres of public land. In exchange, homesteaders paid a small filing fee and were required to complete five years of continuous residence before receiving ownership of the land. After six months of residency, homesteaders also had the option of purchasing the land from the government for $1.25 per acre. By 1900, 80 million acres of public land had been distributed. 1

As significant as it was, however, the Homestead Act was not the top news in 1862. The overriding issue for President Abraham Lincoln and the rest of the country was the progress of the Civil War, then in its early days. President Lincoln had been elected in November of 1860; Fort Sumter fired upon in April of 1861. By 1862, the country had already experienced the first Battle of Bull Run, and the Union was not doing well. The few Union victories of 1862 were concentrated in the west and orchestrated by General Ulysses S. Grant, in contrast to the eastern campaign under General George B. McClellan.

During these early days, President Lincoln called for volunteers to fight for the Union. While the vast majority of enlisted volunteers were young men, many teenage boys and older men also signed up. James Cameron, the middle-aged Scottish immigrant who had arrived in the United States just ten years earlier, was one of them. He marched off to war, leaving his pregnant wife Annie in Oshkosh, Wisconsin.

It is difficult to trace James Cameron’s military career in the Union army. However, with a pregnant wife in Wisconsin, it is reasonable to speculate that he joined an infantry regiment either in Wisconsin or in one of the neighboring states. Illinois, Iowa and Indiana were heavily represented in the western campaign, eventually forming the bulk of the Army of the Tennessee under General Grant.

In 1862, Grant was the only general actually moving forward and winning battles, beginning with forts Henry and Donelson in February of 1862. If we assume James was with this portion of the army, he might well have participated in the Battle of Shiloh in April, then continued with other Midwestern regiments through the siege of Corinth, Mississippi under General Henry W. Halleck, who led the army before Grant was given total command.

By July of 1862, this portion of the army had fought their way through to Memphis, Tennessee. It was about this time that James was killed, leaving Annie alone to raise their infant son, John James Cameron.

Oliver Cameron was uncertain how they managed in those early days:

I think that his mother had some kind of a stipend, some income from some property which they owned in Scotland, but that’s all I know about it.

However, according to other family sources, Annie Cameron refused aid from her husband’s family in Scotland, and returned their letters unopened. An account by Oliver’s cousin, Barbara Silver, gives additional details:

My Great Grandmother, Annie, was born blind but at age 6 gained her sight. She never attended school, but her brother taught her to read the papers. She and her siblings came to America when she was 18 years old.

When my Great Grandfather, her husband, James Cameron, was killed in the Civil War, she refused help from his family in Scotland and made her way as a washer woman. In the 1870 Census, it indicated that her mother Mary may have had a disability, as well.

Annie’s husband James had been married before and had three children from that union. Annie never was asked to care for the step children, but raised the son born to her shortly after her husband, James Cameron, was killed and buried in a trench reportedly in Memphis, Tennessee. 2

John James grew up in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, where he enjoyed skating and iceboating on Lake Winnebago in winter, and sailing in summer. In his home town he also encountered a young woman of French descent, Rose Alexia Bryse, whom he bragged was the prettiest girl in a town of pretty girls. They married in 1883 and resided briefly in Eau Claire, Wisconsin, where they started their family. Sadly, their first child, Chester, died in infancy. The next child, daughter Rose, was born in 1885.

The provisions of the Homestead Act made Montana an appealing destination for many young people who were just starting out, and for older folks as well. The Territory of Montana had been carved out of Idaho Territory in 1884, and was growing. By 1889 it would become a state.

When Rose was five months old the family, including Grandmother Annie, pulled up stakes in Wisconsin and moved to Big Timber, Montana. According to Rose, they endured a “terrible hard winter” that year. Local ranchers lost many cattle, and John James found work skinning cattle that had died in the cold.

A short time later they acquired land on the Sweetgrass River near Big Timber. They lived in a big log house for several years. Most of their 12 children were born there, including Ed, their fourth, born on March 2, 1891.

Grandmother Annie, meanwhile, staked out her own homestead adjoining her son’s ranch and lived there alone. Around 1894 John James sold his ranch and moved onto her property. A couple of years later the whole family moved into town and bought a store.

In 1900 John James moved the family and again tried his hand at ranching, on a ranch along Cottonwood Creek, twelve miles west of Lewistown. Later they moved to another ranch along the same creek. The last of their children, Helen, was born in 1904, and Grandmother Annie died that same year.

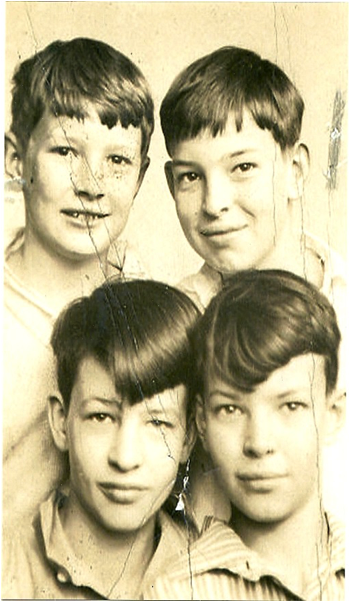

Photo from the Cameron Family Collection.

Ed didn’t share a lot of information about family history or his own youth, but Oliver managed to learn that his grandfather, John James, apparently was not easy to live with—at least, not for young Ed. Oliver speculated that John James, as a boy and as the only child of a slain Civil War soldier and a widowed mother, may have grown up “spoiled.”

Whatever the truth of the matter, Ed quarreled with John James, borrowed thirty dollars, and left home. He was just fourteen years old. Since he’d been raised in rural Montana, he was well equipped to work as a ranch hand, even at such a young age. According to Oliver, it was not uncommon for teenage boys to be on their own and doing a man’s work in that time and place.

After the Civil War, a man named T. C. Power began a number of entrepreneurial enterprises in Montana, later becoming the first senator from the state. One of his investments was a large cattle ranch near the Judith River. To manage the enterprise, he contracted with a ranch manager named John Norris. They named the ranch the P-N Ranch, for Power-Norris.

The P-N Ranch is about a hundred miles due north of Lewistown, Montana. One of the oldest of Montana’s ranches, it continues as a working ranch of historical importance into the present day. Ed eventually made his way to this large corporate ranch to work as a cowboy. By 1916, when he was in his mid-twenties, he was riding line and cooking for roundups.

According to his daughter-in-law, Eula Mae Cameron:

[Ed] told tales of the big Montana round-ups where his contributing art was cooking over campfires and preparing food in a cook tent or from the back of a supply wagon. “Cookie” was a very important part of the operation, and it behooved the Boss to provide a cook that was good. Dad’s pancakes and “mush” were still top-notch when we were sampling them.

In an interview with his daughter, Dorene, Oliver related a bit about life on a big ranch.

Back then there were no fences. The cattle were free to roam in a specified area and were contained by men on horseback riding around the cattle to drive the strays back into their grazing area.

It seems Ed was the quintessential cowboy, and not one to back away from a confrontation, as Oliver revealed in this story:

This is of a time when the neighboring homesteader saw an opportunity to take advantage of the well-traveled dirt road across his ranch. Ranchers had been using the road many years to move cattle. The only other way to get across was to go a long distance around the ranch. The rancher let it be known that they could no longer take cattle across his property unless they paid for use of the trail. But the trail had been used for so long that the other ranchers believed that it had become a public right of way, which he could not close off.

Dad and his brother-in-law Johnnie Sanford were driving a herd of cattle down this road one day. Johnnie traveled ahead on his horse to make sure that the gates along the side of the road were all closed so that the cattle wouldn’t stray. Dad, coming up behind, encountered the hostile rancher and one of his ranch hands, both carrying pitchforks. The ranch hand walked out in front of Dad’s horse, the rancher approached from the side.

He told Dad, “You will need to take your cattle around. This is my property and is not open for travel.”

Dad was strong, quick and agile. He also was very good at managing horses. He had his horse trained so that he could dismount from either side. Most horsemen dismount only from the left. Dad quickly slipped off the horse on the far side, which was not expected. He slipped under the horse’s neck and knocked the ranch hand to the ground. In the next instant, he knocked out the rancher.

When Johnnie returned over the rise shortly thereafter, he saw a commotion and spurred his horse ahead. As he approached, he saw both men sprawled unconscious on the ground along with their pitchforks.

Johnnie asked, “Are you having problems?”

Dad answered, “No, there is no problem.”

The novelist Zane Grey, who wrote epic western fiction, traveled extensively to research his books. It is not surprising that he might stop by the P-N Ranch:

One of the highlights of those days to Dad was the time Zane Grey came by the ranch to soak up authentic flavor for his novels. I can’t remember which of his novels he was writing then but forever after, Dad was a Zane Grey reader. –Eula Mae Cameron

Ed took note when a young woman named Pansy Viola Wood came to work at the P-N as a domestic. Her family had relocated to Montana from Minnesota when she was a young teenager. By the time she met Ed, she was in her late teens or early twenties.

While Ed had received a third grade education before striking out on his own, Pansy had spent more time in school and with an aunt “back east,” and been educated in some of the finer things of life, such as how to keep house properly and set a table.

Needless to say, the smart, self-made cowboy and the refined young woman gravitated toward one another. We know little of Ed and Pansy’s courtship, except that Ed made her a leather braided bridle and quirt during his spare time while riding line in the winter. According to Eula Mae Cameron, both Ed and Pansy were horse lovers. Much of their courtship took place on horseback, so this was certainly an appropriate gift. In 1917 they married in Hilger, Montana, where John James and some of the children were running the post office.

That was another pivotal year for Montana as well. There had been a huge influx of settlers and homesteaders into the state during the years when John James and Rose were working their ranch, but 1917 saw the beginning of a drought that convinced many of the state’s farmers to move on in search of better farming and living conditions. Records suggest that 65,000 of the nearly 100,000 homesteaders left the state between 1918 and 1925. This pushed Montana’s economy into a depression well before the Great Depression began in 1929.

Many relocated to Washington, Oregon and California. John James, Rose and their younger children moved from Hilger, Montana to Blaine, Washington.

Blaine is a small town in the extreme northwestern corner of Washington State. The northern edge of the city limits lies along the Canadian border. The town, established during a short-lived gold rush on the Fraser River in British Columbia in 1858, was incorporated about 1890. By the early 20th century, the town had five fish canneries, including the large, well-known Alaska Packers Association facility. Employment was also available in timber and agriculture. John James found a job in the lumber industry, and worked and prospered in Blaine for several years.

Meanwhile, Ed was finding that work as a lineman and cook for the P-N did not pay enough to fulfill the dream of owning his own ranch. The newlyweds shortly joined the rest of the family in Blaine. Ed found work on a ranch, and still hoped to buy land of his own. However, finances were still an issue for the growing young family, so he later went to work for a small sawmill near Bellingham.

As was common for the times, Ed and Pansy had begun their family shortly after their 1917 marriage. Tragically, their first child, a son, did not survive. Their second child, Oliver E. Cameron, was born July 15, 1921 in Blaine.

Photo from the Cameron Family Collection.

Oliver related that he had health problems as a baby:

I almost died when very young, perhaps less than a year. I had dysentery along with many other babies at that time. I don’t know what disease it was and there was no cure known. Because antibiotics and sulfa drugs weren’t developed yet at that time, the doctor told my folks that the only hope for saving me was to not feed me for a week or so, to only give me water. My impression is that I was a nursing infant at the time.

After about a week, Mom couldn’t stand doing this to her baby and nursed me just a little bit. The dysentery started again, which prolonged the time for which I couldn’t be fed. Amazingly, I survived and recovered on my own. There were a lot of infants dying from this. After that, I was put on a bottle.

To the east, near the little town of Snoqualmie, Washington, the Snoqualmie Falls Lumber Company began operations around 1917, and was soon acquired by the lumber baron Frederick Weyerhaeuser. It was the second all-electric sawmill in the nation, and would continue to be a major employer and provider of lumber products for nearly a century.

Responding to a company advertisement, Ed wrote and applied for the position of sawyer—a highly skilled job that paid well—and got the job. He moved his family, which now included Oliver’s younger brother Keith, to Snoqualmie Falls.

A company town for mill workers had been built across the river from the town of Snoqualmie. It included such amenities as a hotel, a community center, a 50-bed hospital, a barber shop, and rental housing of various sizes. The Cameron family began their life there in a four-room house, graduated to a five and then a six room house as the family grew, and eventually moved into the largest of them all, the original farmhouse in a location known as “The Orchard.” The location had once been an actual orchard, and fruit trees still adorned some of the back yards.

According to the Snoqualmie Valley Historical Society, there were two mills. The main band saw at Mill #1 could handle logs up to eleven feet in diameter. Mill workers routinely processed the large-diameter old growth timber of the Northwest forests, a difficult and often dangerous activity.

Ed had one of the most demanding and intricate jobs in the mill, that of the gang rip saw operator. The gang rip saw consisted of several blades moving in various directions to cut the big logs into lumber. According to Oliver,

He had a bunch of levers there that would move each saw in relation to the others. He had to be watching all the time for things like barbed wire that had grown into the tree, or stones that the spraying hadn’t gotten rid of. He could tell by the sound of things if he was just cutting wood, or if he could hear it cutting something else, he would back off and look to see. That was a job that required a lot of constant concentration. He worked eight hour days. The mill worked three shifts.

Ed remained a man of toughness and action. With his extensive background as a Montana cowboy, he was not afraid to deal with a threatening situation as needed. Oliver obviously admired these traits in his father:

A relatively new employee was running the machine after Dad, and one day felt like Dad was pushing him. He couldn’t keep up with Dad. That whole mill was designed to operate at a certain pace. That fellow wasn’t up to the job yet or wasn’t able to do the job, and this slowed down the whole mill. This fellow one day got angry and picked up a two-by-four to hit him. Dad saw him coming, jumped him, knocked him down and took the board away from him.

There was a rule at the mill that whenever there was a fight, both men would be immediately fired. Dad, knowing this, gathered up his things and turned off his saw, shutting the entire mill down. He walked up to the mill office, which was quite a ways, and asked for his paycheck. The foreman immediately started looking to see why the mill was shut down.

After hearing the story, he said, “Why don’t you just go back to work?”

While Ed was getting established in Snoqualmie Falls, his parents moved to Bellingham, Washington, about 110 miles to the west. Ed’s father was now in his sixties, but the two men were still estranged.

Oliver relates that the only time Ed went to visit his parents was at his mother’s request. She was ill and wanted to see her son, “Eddy,” and his family:

Dad loaded up the family and took some extra gas cans and tied them on the running board. He took off after work and drove all night until he used up all of the gas. Then we had to wait by a service station until it opened to buy more gas.

After we got there we stayed with Dad’s brother-in-law and sister. They had two kids that were older than us….Grandpa didn’t want to be around Dad. He wanted to see us kids.

Those cousins took a couple of us to the cigar store that Grandpa owned. He was a big man, rather portly. There was a cigar store Indian [carved wooden statue] out in front of the place. He [Grandpa] gave us a couple pieces of candy.

Rose Alexia Cameron died in Bellingham in 1932. John James went to live with Ed’s sister, Esther, in San Diego, California. He died in 1933.

Photo from the Cameron Family Collection.

Health problems seemed to plague Ed’s family. Pansy developed tuberculosis when her children were still very young. She did recover, after spending some time away from the family to rest, but by Oliver’s account she was never again in good health. Her frequent pregnancies may have contributed to her frailty. Oliver himself had a bout with polio when he was about six, leaving him with one leg shorter than the other.

He was eight years old when the Depression began in 1929. Fortunately, the mill continued to operate, but with the economic hard times and his growing family, Ed was never able to save much money. There would eventually be six children: Oliver, Keith, Phillip, Adrian “Carol,” Jessie Mae, and Dean “Del.”

Although Ed was never able to buy his dream ranch, he was able to acquire about six acres of “stump land” when Weyerhaeuser made logged-off land available to their employees at prices they could afford. Oliver recalls Ed paying something like twenty dollars down and one dollar per month to purchase his home site. This was bare ground, or rather ground with large stumps still dotting it.

In those days, loggers would use springboards to enable them to cut a tree well above ground level, leaving behind a stump as high as ten feet. The owners of such “stump farms” would salvage the wood for building material, such as hand-split cedar shakes, and for firewood.

Oliver began what was in effect a long apprenticeship in how to convert raw land into a functioning homesite:

I spent many hours of my youth working with Dad to build up our place on this land. Dad would give a task and, being a quiet, calm man, would leave me on my own to figure out how to do it. If more explanation were needed, Dad would give it. I learned to dynamite out the stumps for farmland; I built a belt saw to cut firewood from an old car engine. The flywheel was crafted from the wheel rims. I loved the intrigue of this type of work.

He worked closely with his father, learning the details of engine repair and craftsmanship simply by being with his father as the family worked to build and maintain their home:

I remember helping Dad build a chicken coop. across that alley behind the houses, he built that chicken coop back there. Of course, that was still during hard times. There was a row of garages that went with each set of houses…I remember going there and helping Dad or watching him work on the car. The engines didn’t last long like now. If it lasted 20,000 miles you were doing good. Anyway, Dad was something of a mechanic too. I remember when I was little, him being under there, and [me] handing him the tools.

Even when Oliver was not shadowing his father, he was alert, observing and learning from the activities going on around him:

When I started school at six years old, before I had polio, there were a couple of carpenters building houses at the end of the row of houses that I had to go by. I saw what they did on my way to school and then when I came home again. I watched them laying joists, subfloors, putting up the walls. And that’s when I learned to build houses. When they went home, I would go over there and pick up the nails laying around on the ground so I would have nails.

In addition to acquiring his “real” education by observing the work of the men around him, Oliver began collecting tools and working with them while still a young boy. This fascination with tools, their design and manufacture, would become a major focus of Oliver’s life. Even at this early age he was exhibiting the innate engineering and design talents that would mark his life:

When we were at the 5-room house, I was wandering out in the trees out back. I came across a broken crosscut saw. I brought the longer piece home. The loggers would leave files sticking in a stump. So, I had a collection of files. I just about wore the teeth down on that saw learning to sharpen it.

A nearby commercial dairy farm, Meadowbrook, had a well-equipped blacksmith shop. The blacksmith took time to contribute to young Oliver’s education. Oliver tells of making his own knife blade from a bit of soft iron from an abandoned car top:

Of course it was just very mild steel, maybe not even steel. So, naturally it wouldn’t hold an edge, so I asked my dad about it.

He said, “Take it over to the blacksmith at Meadowbrook,” so I took that knife and was standing inside the door watching the blacksmith working, with the forge going, and he asked me if I wanted something. I showed him my knife and told him the problem, and he asked what I had made it out of, and I told him.

He wasn’t encouraging, but said, “Let’s give it a try, maybe we’ll luck out.”

He heated and cut the blade. When he pulled it out…he touched it with a file, and then he took a little time and explained to me the difference in iron, in that steel is iron with a certain amount of carbon worked into it, and this piece had practically no carbon in it, so he said there was not a whole lot that could be done about it.

That was when I was six year old, I guess, and I remembered what he told me….

He did remember, and later applied his knowledge to a broken piece of saw:

Anyway, I started fooling with tempering it. In those days most men knew quite a bit about that sort of thing; they grew up on homesteads and so forth. My dad gave me a few pointers. He said get it red hot, but don’t let it start shooting sparks out of it, because that’s burning out the carbon. Then plunge it, and then you have to heat it up again, but not so hot this time; heat it until it’s maybe a dull cherry red and plunge it, and that will draw the hardness out of it. So I tried it again, and heated it just a little hotter and let it cool, and I did have a workable piece of equipment. And that’s pretty much the way I learned.

At this point, Oliver was in second or third grade. Unsupervised, he heated his saw project with a blowtorch propped in a stack of bricks to create a small furnace.

Of course, Oliver participated in all aspects of life on a small farm. He helped with everything from washing dishes to chopping firewood and tending the farm animals. While he resented his mother’s insistence on formal table settings, and the extra dishwashing it created, he recalled milking cows in a slightly more favorable light:

As soon as I was old enough I would milk the cows because Dad was usually working nights. It took me twice as long as Dad to milk. We got beet pulp from the beet factory. That was part of the mash we fed the cows. One cow got into the barn and ate a bunch of that beet pulp and foundered itself. I went down in the morning to milk, and it was laying down all bloated.

I woke Dad up, and with a pocket knife he measured from the spine, and from the hip he measured with his hand. He jabbed the thin blade in and gas came out. Pretty soon, the cow got up and I milked it….

Overnight they would lay with their tail in the gutter, and wanted to slap it around, so we would tie the tail to the far side to control it. Down on the creek Dad built a milk house. We could set a can of milk in the creek or in the milk house shaded by the trees.

We put the milk in big pans and they went on shelves so the cream could rise. I would strain the milk into those pans and then skim the cream off the other pans. The milk would sour quicker than the cream. I would scoop the cream up and take it to the house, and Mom or whoever would make butter out of it, and then [with] the clabbered milk we would make cottage cheese. We always had more than we could use. The clabbered milk went to the chickens. Sometimes we would make cheese.

He also learned to garden and to harvest wild food from the Pacific Northwest forests. This included grass and clover for a bunch of angora rabbits the family owned for a time. Being the eldest child with parents who were overworked and in poor health, he took on many of the child-rearing duties, such as waking up his siblings, getting them ready for school, and preparing their breakfast and school lunches.

By his own account, Oliver himself only went to school out of obedience to his folks. He was aware that his education was important to them, and something for which they sacrificed. Nevertheless, he felt there was little benefit to formal education, and did not put his full effort into getting good grades:

I didn’t like school anyway. It didn’t make much sense to me. Dad didn’t have that kind of education and yet during the Depression the neighbors came and asked him how to do things. A lot of it was just stupidity as far as I was concerned. I learned what I wanted to learn from it.

Oliver remained true to his penchant for self-directed learning. Later in life he would confess:

Reading has been my whiskey. It’s not just any kind of reading; it’s been reading all kinds of things. That, and then the influence of my father, who was a very adaptable person, and growing up during the Depression when he had the initiative and the know-how to get hold of a piece of property, unimproved stump land, and turn it into a home….

In addition to doing chores and homework, Oliver held various part-time jobs before he graduated from high school. He worked at the traditional jobs that were open to teens in that time and place. He picked fruit; he worked at a garage pumping gas. The latter job enabled him to buy his first car, which he cut down and turned into a pickup. This in turn opened the way for additional entrepreneurial pursuits:

Then I cut shakes, shingles. I would go out where they had logged out and find a cedar long butt or big stump and cut it into shingle bolts or shake bolts and sell it to a shingle mill. I would cut firewood out like that too, and sell it by the cord.

His last summer in high school, Oliver got a job as a section hand with the Northern Pacific Railroad:

We had a gas car, a little spider-like thing that runs on the rails. It has a couple of ties so that you could pick it up and turn it around to get it off the tracks to let the train go by. If we were working in a place where we couldn’t see the train coming, we had something like a cap gun cap that we would sit on top of the track so that when the train hit it, it would make an explosion that would let us know the train was coming.

The wooden tracks would get rotten and have to get replaced. That was one of the biggest jobs. We’d dig out right under the tie and put the new one in, and then pry it up against the rail, and then shovel gravel under it so that it was tight against the rail. There was a little plate on top of each tie for the rails to sit on with holes in them for spikes. A spiking hammer has a small head and is double-ended, so you have to be pretty accurate with it. I was good at that. I got to drive the spikes. That was just because I was raised using tools.

There was a little gap left between the ends of the rails. In the summer they expand and when cold, they contract. There is nothing to hold them, nothing to keep the rail from moving forward or sliding down hill. There is a kind of a C clamp you put on one side and pull it up on the other, then clinch it down on the rail to keep it from moving downhill. The rails manage to creep downhill anyway, so you would have to cut a half a rail or so off so that the rails wouldn’t expand and buckle. That was another of our jobs.

I enjoyed that job! Hard work!

Graduation day came. Oliver wryly suspected he was given his diploma to get him out of the school system, in which he obviously had little interest. True or not, Oliver was now a high school graduate and quickly made his way to full-time work in the wider world. He had a little time to experience life as a young man in Washington State before events in that wider world spun his life in a different direction.

He worked a handful of odd jobs, then moved about seventy-five miles due west of his Snoqualmie home to Bremerton, Washington, where he took a job at the Bremerton Concrete Works:

My first job there was running a machine that made concrete blocks. You had a form and you filled it with green cement, and then it had to be tamped. That machine I was operating tamped the pasty cement. It wasn’t really runny.

And then they got an order for guard rail posts. They were about 14 inches in diameter and seven or eight feet long. They weighed about 55 pounds green. I would grab one, bend my knees, pull up towards my chest, flex my legs. I had good legs. Someone would kick the pallet out from underneath, and I would set it down.

While working another machine, Oliver experienced an industrial accident that gave him a bit of empathy for the blind. Although his injury fortunately resolved itself after a few days, he never forgot the experience:

I was operating a batch plant filling ready mix trucks. The cement came up a conveyor on sacks and spilled off the conveyor into a chute that brought them to a platform, right handy there. The hopper above that mixer was a scales. You pull a lever, and a certain amount of gravel would go in, and pull another and sand would go in, and pull another and water would quirt into that hopper, then you would reach around to your side, take your sharp trowel, and slash the cement sack. You grabbed both ends, picked it up, turned around, and tipped the thing over and pull the two ends together so that the cement dumped into the hopper.

Trucks are waiting, so you are in a hurry. I reached around and cut a bag open and stuck my trowel in my holster. Then leaned over to pick that thing up and here come another bag of cement down and hit the open end of my opened sack and made a geyser of cement, right in my face.

The cement is really finely ground. It felt smooth and didn’t hurt, but as soon as it started mixing with my tears, that was something else again.

I felt my way down and went into the office. They kept a first aid kit there with a little eye cup. I tried to wash my eyes out. Somebody took me to a doctor. They irrigated my eyes again. Then they bandaged my eyes so that the light couldn’t get in. I had to have that bandage for two or three days. Even after that, it took quite a long time before my eyes quit being sensitive to light. Of course, it was not hopeless for me. I knew that I would be able to see OK, but it sure gave me a feeling for what blind people have to do.

He quit soon after, feeling that the pace and pressure of the work were too much. He went from Bremerton to the Olympic Peninsula to be part of a firefighting crew on the Dosewallips River, where he was more in his element. Even his early childhood efforts to learn saw sharpening came in handy:

They had been fighting that fire for a couple of days before I got there. We were making a fire line around part of it. We were using a Pulaski, and they had a box of files in the cook tent. I put three or four of them in my pocket. There were some fallers falling snags. I was sharpening my Pulaski. Those fallers saw me sharpening that, and they wanted me to sharpen their axes, so I did.

Oliver and another young man were left to monitor the fire after the worst was over. They spent their days hiking mountain trails searching for and extinguishing “hot spots.”

During this time Oliver also worked for the Service Fuel Company, which sold firewood and coal. They used a large buzz saw to cut firewood. Oliver described the system:

The buzz saw had a 1-cylinder engine, a putt-putt…The way you started it was by giving those flywheels a good pull against the compression. I wasn’t very heavy, probably 155 pounds, but just heavy enough to pull the flywheel over to get the thing going. When the piston goes down, some gases go in. When it comes back up, it compresses that gas and then a spark explodes. When we pulled the flywheel it would start it running. Running that big buzz saw was one of the biggest jobs I had there.

He also shoveled coal to sell to homeowners by the sackful. This job ended when a relative of the owner wanted the position.

But by then the world was at war.

_______________

1Act of May 20, 1862 (Homestead Act), Public Law 37-64, 05/20/1862; Record Group 11; General Records of the United States Government; National Archives.

2Ancestry.com by TANDBSILVER, Barbara Silver re: Anne Bennett 1830-1904. Used by permission.