The decade of the seventies was a time of transition and change for Oliver, now in his fifties. When Rene left, Oliver liquidated their major assets, except for the land and improvements, and gave Rene the cash to help her establish a new home. Dorene and Oliver continued to live for some months in the original house built in 1963 even though high water and spring ice melts were eroding the nearby river bank, endangering the house. (In later years it would crumble over the edge and into the river.) This was the threat that had inspired the building of the new, larger house further from the river bank.

Dorene remembers the year 1969 -1970 saw an influx of “white people from outside,” as newcomers came to live in Ambler and the surrounding area. One new couple was Bob Schiro and his girlfriend Judy Galblum. Richard was away at college and Rene had taken Gary with her to Idaho, but this void in Oliver and Dorene’s lives was partially filled by the new arrivals. Oliver welcomed these newcomers to the area and helped them in whatever way he could to adjust to a strange place.

Dorene recalls:

Dad and I had a house full of company for at least half of the nights that year. It was great fun for both of us to hear the tales of these many newcomers. Most of them were there because they knew someone who came before them…Each built some kind of a home to live in quickly before winter came in early October. Dad had long conversations about building methods and survival techniques in this remote area of the earth. He lent tools, boats, nets and whatever else we could spare to help them get started, as well as his knowledge.

In 1977 a study was published about the native lifestyle along the upper Kobuk River. Headed by Dr. Richard Nelson under contract with the National Park Service and Brown University, the study, titled Kuuvanmiit Subsistence: Traditional Eskimo Life in the Latter Twentieth Century, includes information on this influx of settlers:

All of the Kobuk River villages have small numbers of non-Native residents. These are primarily schoolteachers and church leaders, who remain in the area for only a few years…Over the past two decades, however, a permanent subcommunity of non-Natives has established itself in the upper Kobuk River Valley, particularly in the village of Ambler….In 1975 there were twenty-nine permanent non-Native residents in the upper Kobuk region. Of these, sixteen were living in Ambler….All of the settlers obtain most of their staple foods by subsistence hunting, fishing, and gathering….The non-Native settlers in the Kobuk River Valley represent a unique and interesting phenomenon. Like modern pioneers elsewhere in Alaska, they have adopted a subsistence lifeway in a remote area of the state. But they are much different in having partially assimilated the indigenous Native culture. In this sense they are most akin to the early American pioneers, who lived among the Indians and became very much like them. Opportunities for this kind of cultural hybridization in North America have been pushed to the northern fringe of the continent, where the last living indigenous cultures are to be found. The Kobuk settlers thus represent a final remnant of the American pioneer tradition.1

While Oliver was among the early settlers noted in the study, and a great resource for the newcomers of the early seventies, his own position in Ambler was shifting. Not only had his household changed so that he was no longer the head of a household in the village, but the community had started to change as well. When the Camerons first arrived in Ambler they were welcomed in the old traditional Inuit manner: newcomers were celebrated, honored and welcomed. Even during the years Oliver and Rene were raising their children, however, local culture began interacting more with the world at large, and racial tensions and conflict began to escalate. Oliver, by the time he was on his own at the homestead, had begun to reassess his role in the community and his place in the world.

When the opportunity arose in early 1970, he sold the buildings and the best three acres of the land, dividing the proceeds between Rene, Richard, and Gary. The new house the Cameron family had built that Oliver dreamed of turning into a Bible school, went to new owners. While the Cameron family never lived in their new structure, it was inhabited until early in the new millennium and may have been one of the longest-used sod houses in the area.

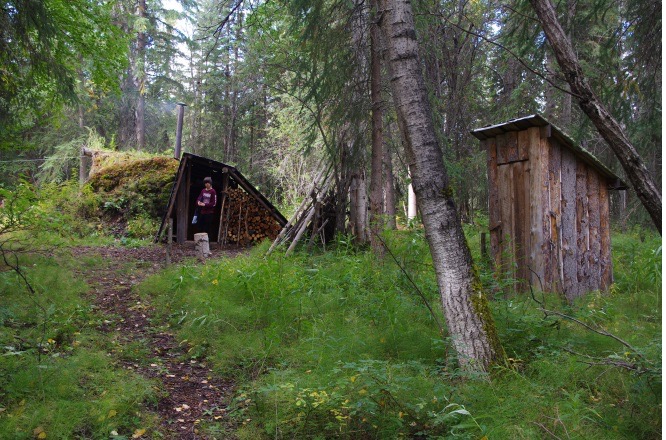

Dorene and Oliver moved into a tent on the remaining two acres. They spent that spring and summer cutting poles to build a new sod house. Their neighbors, Bob and Judy, helped with hauling and peeling the poles. Oliver, however, had a father’s heart. While Dorene’s presence must have been a comfort, she had experienced little of the wider world. That summer he recommended she leave Ambler to broaden her education. She had saved money from her summers of working for the owners of the Hansen Store in Kotzebue, so could afford a ticket to Idaho. She lived a short time with her mother in Nampa, then rented a nearby apartment with her brother Richard and took classes in nursing while he finished his degree at Northwest Nazarene College (Rene’s alma mater). Richard then began his working life, eventually establishing his own construction business.

Oliver, meanwhile, finished the small sod house they had begun and lived in it that winter and the next. While Oliver had neither sought nor welcomed any of these developments, his new freedom from family obligations now gave him time to pursue and refine what was the core of his identity and sense of self-worth: religion and his philosophy of life.

During his years as a husband and father he had broken further from Rene’s and his parents’ concepts of Christianity. All during the children’s growing up years he spent time talking with his children and his friends, explaining his views. Religion was his favorite topic, one his children perhaps—occasionally—grew weary of hearing. The traditional religious points of view did not make sense to him and he put great time and effort into developing a belief system that did. He also, from the time the children were small, put his thoughts on paper, usually in letters to family and friends. Eventually these morphed into a booklet. Dorene assisted in getting each new version of the booklet printed, and these writings became a catalyst for conversations with new acquaintances, leading to deeper friendships and ongoing talks and visits. Living alone he began writing in earnest, putting together a manuscript that would become the full-length book, Thoughts Born of Turmoil.

All the while he continued to develop his skills in living a sustainable, handcrafted lifestyle based on local materials and resources.

When Gary turned eighteen and moved back to Ambler with a girlfriend for a brief time in the seventies, Oliver deeded him a parcel of the reduced homestead. When Gary moved onto that property, Oliver built himself a small log cabin and, over time, added several caches. He lived in that cabin the remaining years of his stay in Ambler. Gary’s friend did not adjust well to the pioneer lifestyle and they parted ways. Gary, after returning to Idaho, eventually met Leona Ireland. They married in the mid-seventies and had three children, Melinda, Benjamin and Luke.

Oliver was active and single, so it was only natural that he made new friends, including women. One of these was Thelma Clark, whom he had initially known while living in Meadows and New Meadows, Idaho in the early sixties, when the Camerons lived and worked there. She was now a widow in poor health, and they renewed their acquaintance. Oliver went to visit her in Idaho in early 1973 and both believed he helped restore her health, possibly saving her life. As Oliver was flying out to see Thelma, Dorene was flying in to return to Alaska from her time in Idaho, their paths crossing briefly in Fairbanks. Thelma returned with Oliver to Ambler in the spring of 1973. She was a welcome addition to the community, a spunky woman who adjusted easily to the homestead lifestyle. However, she would lose income from her late husband if she remarried, something she could not afford. Neither was she comfortable staying with Oliver unmarried, so she returned to Idaho within a few months. Dorene had lived next door in Gary’s former house while Thelma was there, but moved in with Oliver after she left to save heating both houses.

Neighbors Bob and Judy had left for a time, and he came back alone in 1974. He and Dorene became a couple. Bob and Dorene lived about a half-mile from Oliver, and continued a close relationship, socializing with friends or working to gather fish or butcher caribou meat.

While Oliver struggled with serious health issues during the late seventies and early eighties, he stayed very active in the community, creating bonds with neighbors in Ambler that lasted his lifetime. When Bob and Dorene moved to Homer, Alaska in 1979, Oliver missed them, but continued to maintain old friendships and build new ones with his neighbors.

Introduced through a friend, Oliver began writing to a young divorced woman in New York, Carol Schlentner, who longed to return to Alaska. In June of 1980 he wrote to Dorene from the tiny Alaskan community of Manley Hot Springs, about 150 miles by road west of Fairbanks:

She has a girl 8 and one 2 years old and has been living in N.Y. with her folks. She wrote… wanting to correspond with someone from up here, so I wrote to her. She is really unhappy where she is and wants to get back out in the bush again up here somewhere. To make a long story short, she and the girls are coming to Fairbanks while I’m over there.

Sympathetic to her unhappiness, Oliver had arranged for her and the girls, Tonya and Paula, to fly to Alaska. Oliver moved with her onto property that Carol owned near Manley Hot Springs and helped her build a semi-subterranean sod house. They finished the project in about a month. They became good friends during this time, and Oliver and the little girls bonded.

Oliver returned home to Ambler later that year, but by now there was less and less to hold him there, with Rene gone and the children living their own lives. Then, in 1981, Gary wrote asking if he could sell the lot in Ambler that Oliver had deeded to him. He was hoping to cash it out in order to finance a new business venture, but withdrew his request when Oliver pointed out that the deed had been a gift.

That incident brought some things into focus for Oliver. In September 1981, he wrote Dorene:

In my own affairs, I seem to be at a crossroad again. A number of things cause me to feel and think that this place has accomplished its purpose in my life and it may be time to make a move.

This piece of ground has provided me with some valuable experience and relationships, but has never been something I’ve felt real satisfaction in. It was a compromise for Rene’s sake….It was probably the right thing to do at the time, but now I feel done with it.

Gary wanting to sell would indicate it isn’t so needed by him anymore, and the population explosion here and the influx of people I don’t relate to seems to me like it can only make the racial problems and tensions worse. And I’m tired, tired, tired of all this tension.

The tensions were created when the native population began to change due to exposure to outside forces: television was introduced; the Native Corporations were established. Land ownership—a new concept for the Inuit—became an issue. Dorene relates that they were told they could not cut firewood near the village any longer since the land now belonged to a Native Group. There were angry meetings held over that as well as fishing and hunting issues, with the local river watched to be sure some folks did not take too many fish. Hunting, which the natives and locals had done as needed and the opportunity arose, taking caribou, ducks, beavers, wolverines and other animals, now found themselves dealing with hunting seasons, laws and boundaries that were annoying and irritating to those used to a subsistence lifestyle. While the natives traditionally made good use of the animals they hunted for food, clothing and other needs, often using every part of the animal, they now were frustrated in their attempts to live a traditional, efficient lifestyle while simultaneously offended by such insults as a single hunter killing 100 caribou to sell their jawbones to the University of Alaska for a research project.

Oliver not only was stressed by tensions and angry community meetings, he worried about “worst case” scenarios as well. One concern was that a crisis or economic collapse in the outside world might cut Ambler off from air flights and outside food sources upon which most villagers were now dependent, leaving the possibility that outsiders, even long-term residents such as himself, might be treated badly. Ambler had ceased to feel like a secure haven to Oliver.

In his letter asking about the sale of the lot, Gary had included some information on land that the Bureau of Land Management was going to open to entry as homesites, headquarters sites, and trade and manufacturing sites in the area west of McKinley Park and south of Tanana. This caused Oliver to chuckle to Dorene:

It was almost as if he was selling me out here and telling me I could go somewhere else.

Oliver’s first impulse was to dismiss the idea, but then he began to consider the possibilities:

It seems foolish to consider starting over again somewhere else. But every move I’ve made since leaving Idaho has had some foolishness about it. It seems to me the course I’ve been following isn’t complete yet….I have a lot to do yet in applying what I’ve learned and learning more to live in relationship to the natural environment in such a way as to gain the most personal development and integrity out of it. Now I have no family ties to consider and no excuse for not doing as seems right even though I’m more aware of the problems than I was when I had less experience of such moves. Being aware of them also means I’ve had more experience with which to face them.

He systematically worked his way through other options. For example, living near Bob and Dorene at Homer was a possibility, and he would enjoy their company, but that area did not appeal to him. What did appeal to him was developing another homestead in one of the newly opened areas – the last land to be offered for homesteading in the United States. There were two tracts, but Oliver quickly centered his attention on the area west of McKinley Park.

He began to make his plans.

1Anderson; Bane; Nelson; Anderson; Sheldon. Kuuvanmiit Subsistence: Traditional Eskimo Life in the Latter Twentieth Century. National Park Service Department of the Interior. 1977. PP 582-586