The village of Ambler is situated at the confluence of the Ambler and Kobuk Rivers about 130 air miles east of Kotzebue. When the Cameron family stopped there for the night in the fall of 1958, the first settlers in the brand new community had just moved down from the upriver villages of Shungnak and Kobuk. That very night the Camerons first encountered the founder and leader of Ambler, Tommy Douglas. The Douglas and Cameron families became close friends in the years following.

Tommy Douglas, a local Inupaiq, was a smart man who learned quickly, a visionary, who had seen firsthand the changes taking place in the native culture over the past decades. The Inupiaqs who lived in the region were gradually shifting from migratory hunting and moving seasonally from location to location, to a more settled lifestyle with the coming of white people in the 1900s. They had a school and village at Shungnak, but Tommy could see there were not enough resources for a growing population. The area where the Ambler settlement arose was a place lush with wildlife, fish, and spruce trees. Like Oliver, Tommy sought an area where he and others could live sustainably with as little dependence as possible on imported supplies. Also like Oliver, he was a deeply spiritual man who believed in divine direction and purpose.

Tommy, who was illiterate as were many natives of his generation, gave his account of the founding of Ambler to the school teacher, James Davis, who then composed the following letter to his own wife in Tommy’s name:

Dear Mrs. Davis,

I know you will be surprised and perhaps a little shocked to receive a letter from a stranger whom you have never yet seen, but your husband persuaded me to believe that you would enjoy reading a few thoughts which I have expressed to him just today. You may blame him for any ill effects, and this unexpected letter from an Eskimo Indian Chief (sic).

I met your husband last fall but our association has been definitely interrupted by my being away from Ambler most of the winter. I recently returned from attending Bible School at Noorvik, an Eskimo village toward Kotzebue from here.

I would like you to know that I appreciate the fact that Mr. Davis has come to us. I know it is the Lord’s doings. He it is that has sent him this way.

About five years ago I was in a religious meeting and the missionary entreated me to become a Christian. Two years he tried in vain to win my heart for Christ. In the spring of ’57 I decided to go to an altar of prayer and yield my heart and life to God, but on the way down I slipped out an exit door instead.

I cannot say how much the missionary suffered in disappointment, but my heart certainly remained heavy, my conscience made itself miserably felt and, in spite of my stubborn refusal to take Christ as my Savior and let Him come into my heart, my soul continued weeping and yearning for God.

The twenty-second of June of ’57, I met a prospector from Fairbanks. He needed a guide to conduct him through the country around Noatak. I was happy to accept the position. He chartered one of the Wien Alaska Airline planes, and, along with his nineteen-year-old son, we took off on the twenty-third of June.

About thirty-five minutes we were in the air prior to an impact by very rough winds which persisted in blowing us downward. Wien’s pilot tried in vain to gain altitude and explained that he could not turn back because of proximity of mountains on either side.

For the next fifteen minutes we three wondered if this was truly to be the end for us. It was journey’s end for the pilot and he burned with his plane, but the son, sitting in back with the luggage, was not hurt. He carried his father, and responding to my calls, came back to help me. I had lacerations on my head and face. My right arm was broken. My pelvic bones were broken in three places. My lower body was crushed and my left leg was torn from its socket joint. There seemingly was nothing to hold my hips together and I was temporarily paralyzed from my waist down.

My rubber overshoes having burned, flames were now consuming my feet. I saw them eat the flesh from the bones of my right foot while the twisted wreckage held it in such a vise-like grip that I simply could not free myself. I can never forget the protrusion of my blackened toe bones.

Finally, in desperation, and with the added impetus afforded by the surging heat and flames, I told him to pull me from my foot which was so inextricably caught.

He got a rope around my leg, and wrenching my body with rough determination, complete abandon, and an all-exacting tug, pulled me free. My foot came too, but by that time it was so charred that amputation had no alternative.

Bleeding and mutilated to the extent of human endurance, my clothes mostly torn and burned from my body with no way of getting word to anyone, all of whom were beyond the radius of an unknown number of miles of untraveled terrain, without even the comfort of God in my heart, you can well imagine the thought playing upon my mind as I lay pressed in the raw, upon the bosom of Mother Earth for eighteen solid hours awaiting a faintly possible rescue.

I knew this was also the bitter end for me. The pilot, an admirable and much loved young white man who had married a beautiful Eskimo girl, had met a comparably brief though violent death in the chaos of the wreckage and flames. Mine was to be more lengthily drawn out affair permeated with the excruciating pain of a depraved heart, physical distortion and fire.

But I knew I was receiving only what I deserved. I was getting what I had been asking for. No more justice was being measured out to me who was ignoring the sacrifice of God. The poet Robert Service said, “The Arctic trails have their secret tales that would make your blood run cold.” I think I got the idea.

I thought of my darling wife, Elsie. I own a saw mill and I wondered, what shall I do about that now? I thought of the missionary and the bitterness was intensified for having spurned God’s call to my heart. I came to tears and to prayer. As I prayed I looked up toward Heaven. I believe I was looking into the face of Jesus. I asked Him please to spare my life, return me to my parents, and I promised to become a Christian and always serve the Lord.

Somehow, the Lord relieved me from all sense of pain and a helicopter picked us up and took us to Kobuk. Wien Alaska Airlines flew us from there to Kotzebue from where we were flown to Fairbanks and the doctors.

The doctors said that I could not possibly live, but I encouraged them saying, “Oh yes, I am going to live.” It is still a mystery to the doctors that blood poisoning did not claim my life, but all I would say is that it is no mystery to God.

While recuperating in the hospital, the thought kept impressing itself upon me that I must move from Shungnak to Ambler.

Now, there was no Ambler then, no houses nor anything but a bleak, wild and desolate place in a wooded area where two rivers joined. I did not understand at first why the thought kept reoccurring to me, but I soon realized it was God talking to my heart.

I continued on at Shungnak until early summer of ’58, then I located at Ambler.

A hard winter ensued and I prayed for my Lord about it all. Immediately caribou, moose, ptarmigan and wild game in abundance began crowding upon Ambler. Fresh fish and food was supplied without measure.

When folks at Shungnak saw this phenomenon at Ambler, they too began moving down. I could not, at first, persuade them to come with me, but physical sustenance became a deciding factor.

Today, not counting the pastor or the teacher, there are eleven families permanently settled here, and we are expecting more to move down from Shungnak this summer.

We built the church house during the summer of ’59. That fall, school materials began coming in along with Mrs. Ross who was supposed to start the school. (I kept praying for my Lord, even while Mrs. Ross was here, “I need a Christian teacher for the children.”) Mrs. Ross never started the school. She went up to Kobuk and taught there instead.

This year there was more than one teacher who was supposed to start the school here. Some of them came, looked the prospect over, and presto, they were gone. In the interim my prayer for a Christian teacher did not cease. At last, in a most obvious answer to sincere prayer, we have Mr. Davis as our teacher. I believe God sent Mr. Davis this way to be a Christian influence upon our children. I know God is working out His will and our children will be more prone to believe and will better learn what it is to be a Christian.

I do hope and pray that this Godly set-up will affect more Christian families to make their home in our new village.

We hope to have a landing field; we hope to have a post office, and to have a Bible school here someday soon. Mrs. Davis, you have been reading a true story, but it did not come from the pages of a “True Story Magazine.” This is a story which helps to explain why Mr. Davis is in Ambler today. It can also help to explain our jubilation upon your arrival next fall.

I think you will like the river, the trees, and the clean lines of our village. It is especially lovely here in the summer time. We shall try to make your stay as pleasant as we know how.

Seeing what the Lord has done already, I anticipate with high hopes what He will do in the immediate future.

I shall keep on praying for my Lord.

Very truly yours,

Tommy Douglas

By James W. Davis

Oliver had claimed his five-acre homesite near Ambler under a 1927 revision of the Homestead Act of 1862, which had played a large role in the lives of his parents and grandparents. Among other stipulations, he was required to build a dwelling and reside on the property for five years. He got credit for some of the time he had spent in military service.

In the summer of 1963 he sent word to Rene, in Idaho, that he’d had their land surveyed in Ambler and had cut, peeled and seasoned enough logs to build a home. He sent money and told Rene that she and the kids could move to Ambler as soon as his summer job in Kotzebue ended. Rene sent some of their belongings to Kotzebue, put some in storage in Nampa, took the rest to the dump. She closed up the house in New Meadows in August and flew to Kotzebue with Dorene and Gerald.

Richard, then 15, had made the trip in advance of the rest of the family. Oliver had gotten him a job helping to build a warehouse for Hanson’s General Store in Kotzebue. Both Oliver and Rene were a bit nervous about having him fly alone, but Rene had arranged assistance for him at each break in the journey. A relative in Seattle met him for the three-hour layover, and a friend met him at the airport in Fairbanks and provided overnight accommodations. While en route, the flight attendant gave Richard a tour of the cockpit, where he saw the gauges and visited with the pilots.

Meanwhile Oliver was busy trying to line up a boat. The big one that they had used to come downriver four years earlier had been battered beyond use by a storm, and he hadn’t had time to build a new one. He ended up buying a somewhat smaller double-ended lifeboat of the type that had formerly been used on whaling ships.

When the family arrived in Kotzebue, the children spent many boring hours cleaning the sand out of the inside of the boat. They also stuffed cotton caulking between the boards, punching it in with a chisel. Oliver then launched the boat, let it sink, and left it until the wooden boards had soaked and swollen enough that the cracks between them were tight.

Oliver used his fifteen-horsepower motor along with a borrowed thirty-five-horsepower to make the trip upriver. It was a challenge to fit the belongings that had been mailed from Idaho, his own things, and his tools into the smaller boat, but eventually he squeezed everything in, and the family started upriver to their new homesite. The trip was slow. It took a long time to move this wide, loaded boat up the river with such small outboards.

The September weather was beautiful but was already cold enough that they had to break ice at one point. Then, on the last night of the trip, it snowed. The two boys, who were wearing only rubber boots and socks, chilled their feet badly enough that Gerald’s toes tingled for days afterward.

About two-thirds of the way to Ambler the Camerons were met by a friend and were able to shift some of their load to his boat. When they arrived in Ambler, they ate a hot meal with friends before motoring the last few hundred yards to their homesite. A crowd of other villagers helped unload the boat. Oliver quickly erected their wall tent and set up the wood stove.

Rene was pleased with the location Oliver had chosen for their new home. The new homesite was outside the village, but within easy walking distance. Situated on a high bluff right on the river, on the north edge of Ambler, the Cameron lot bordered that of a local native, Tommy Lee, who had been their landlord in Shungnak in 1958. A creek ran through the property, and there were a few trees and plenty of grass, while farther back from the river there was a patch of open tundra and beyond that were scattered dead trees from a fire that had passed through a few years previously.

The family was back together, Rene approved of the location, but the differences in values and beliefs between Oliver and his wife continued to widen. They worked together over the next few years to build a home and raise their children to adulthood, but their conflicting worldviews would continue escalating tension in the marriage.

Now, the first order of business was to build a cache to keep belongings dry and out of reach of porcupines, squirrels, and stray dogs. With the help of the children, Oliver accomplished this in a few days. This was a hastily-erected cache, and a couple years later, Oliver replaced it with another more substantial one.

Within weeks of the Camerons’ arrival in Ambler, the overnight temperatures dropped so low that the tent was cold even in the daytime, when the wood stove was going. Rene had struggled to keep warm on the trip upriver even with a bearskin covering, and now she wasn’t sleeping well. After she mentioned this to one of the Ambler women, the community invited the family to stay in one of the Sunday School rooms at the church. Even though it was not very well insulated, it was still significantly warmer than the tent, and they now had a small kitchen area and room for proper beds.

The children helped Oliver with the house, and also began their studies. Ricky and Dorene were enrolled in correspondence courses from the University of Nebraska, while Gary went to the village school just up the hill from the church. This was the first year the newly-built school was in use. The teachers were Dan and Joyce Denslow.

With all these events taking place, Oliver had not been able to hunt that fall, so the Camerons were trading for meat. One day someone came by with a sled loaded with food, including meat, berries, dried fish, and even some store-bought treats as a thank-you to Rene for playing the organ for church services.

When everything was safely stored, Oliver began digging a square pit and leveling the ground for their new dwelling, another semi-subterranean sod house. Freeze-up had already begun, so it was a challenge to level the ground at the bottom of the pit and put down the main floor supports before the dirt froze. Every day he and the children would break through a crust of frozen dirt with a pick to continue the work. Sometimes they covered it with sod in an attempt to keep it from freezing overnight.

Once the floor was roughed in, the next step was to dig holes and set vertical tree trunks in them to support the horizontal members that would define the basic shape of the walls and roof. They then leaned split lumber against the framework at an angle to form the walls, and laid sawn planks on top to form a sloping ceiling.

Finally, they covered the entire structure with a layer of sturdy plastic sheeting known as Visqueen, covered that with blocks of moss for insulation, and backfilled the walls with dirt. The plastic was the key to this type of structure: It kept warm air inside the house, and kept bits of moss and dirt from falling inside.

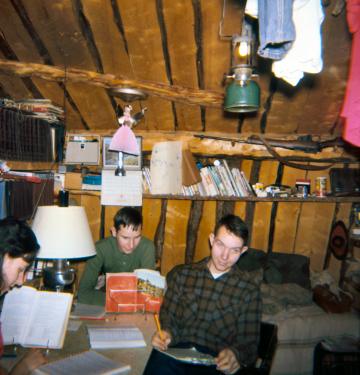

Photo from the Cameron Family Collection.

The family was still living in the church when they heard of President John F. Kennedy’s assassination on November 22, 1963.

By December 5th, the house was ready. With the help of friends, a dogsled, and an early model snowmachine, the Camerons hauled their belongings to the new house. It was snug and warm: with or without a fire, and no matter the outside temperature, the Camerons no longer suffered the inconvenience of having their water buckets freeze at night.

Photo from the Cameron Family Collection.

Oliver had built a portable sawmill with a table-sized blade and a 10-horsepower engine. After the family moved into the new sod home, he continued to improve it, milling lumber to cover the subfloor and finishing the counters and tabletop. After a few months they were able to order vinyl as a final touch for the floor, counters, table, and cover for the water barrel.

Photo from the Cameron Family Collection.

The house was 20 by 24-feet, and comparable to other houses in use throughout the village. Oliver partitioned the back half with curtains, and divided it into two bedrooms—one for himself and Rene, and the other for Dorene. There was storage in a closet, in boxes underneath the beds, and on shelves above them. The boys slept in the front of the house, which also served as the kitchen and living room.

Gerald’s bed was to the right of the main door. Oliver built a desk and furnished it with a captain’s chair for his own use, setting it to one side in the living room area. Richard’s bed did double duty as the couch. Oliver built a study desk and two chairs for the children next to the couch/bed, and hung a kerosene Aladdin lamp over it. Its light was easier on the eyes than that from their Coleman gasoline lantern.

The wood stove, which Richard had made out of oil barrel steel, stood in the middle of the living area. It had a cast iron top and even a built-in oven that Rene learned to regulate for baking bread or roasting fish. She could also open or close the oven door as needed in order to maintain a comfortable temperature in the small house.

Photo from the Cameron Family Collection.

Oliver built an unheated “arctic entry” that created a covered space between the front door of the house and an exterior door. This formed a heat seal and offered space for brushing off snow and for storing boots and parkas. The door of the house itself was covered with caribou skin for insulation.

Once the house was finished, the family settled into a routine. Richard and Dorene studied every morning from 5:30 until breakfast and then again until noon, overseen by Rene. They both earned their high school diplomas by way of University of Nebraska correspondence courses, while Gerald attended classes at the village school.

In December of 1963, Tommy Douglas came to Oliver with a proposal. He wanted to use some of the money he’d received from the insurance company after the accident to start a store, with the idea of providing necessities to the villagers at lower prices. He hoped the Cameron family would operate the store out of their house and be responsible for clerking and ordering supplies. They would be providing a service to the community, and receive discounts on their own groceries. Oliver said that he would think it over.

When Oliver finally agreed, Tommy placed a large order with a firm in Seattle for basic staples—flour, tallow, sugar, tea and coffee, soap, canned milk, oats, rice—and ordered gasoline for boats and kerosene for lamps from the regional supplier in Kotzebue. He also began preparing his own large boat, the Bucky B, to transport the goods upriver once they arrived in Kotzebue.

Once the first barge had arrived in Kotzebue from Seattle and the last of the river ice had flushed out of Kobuk Lake, Oliver and Tommy made the trip down to the coast and brought the goods back to Ambler.

As Oliver and Tommy had agreed, they operated the store out of the Cameron house. Oliver also built a makeshift warehouse in the back yard by laying boards on some 55-gallon drums, where the goods could be stacked and covered with a tent. Oliver also built display shelves in his front room.

The store officially opened in July of 1964. Oliver was in charge of ordering, Dorene and Gerald brought supplies in from the warehouse and helped stock the shelves, Rene worked the cash register, and Richard kept the books. They established store hours in order to protect the children’s study time, but the villagers tended to come to the store whenever they needed something. Rene served tea or coffee, so store visits often became social visits as well.

As the business grew, Oliver began ordering items beyond the basics, such as whole cloves, cinnamon bark, and a variety of teas. He used the money earned from the first order to get additional stock by air from Anchorage and Fairbanks—such things as lamps, boots, dogsled gear, harness material, nets, rope, and some clothing. He kept the markup as low as possible for staples, but charged a little more for non-essential items. He never offered credit. Word quickly spread about the store’s low prices, and customers from Shungnak and Kobuk began boating or dog-teaming downriver to buy supplies.

Once, when Oliver became frustrated with empty candy wrappers littering the yard, he refused to sell any more candy, telling customers that when they began properly disposing of the wrappers, he would stock the candy again. It wasn’t long before they complied and he resumed candy sales.

Later, the store was moved from the Camerons’ home to another location, and more warehouses were built for storage. For a time Rene clerked at the new location in the afternoons.

Photo from Cameron family Collection.

On March 27, 1964, the family heard the river ice crack and knew that something unusual must have happened. Later they heard radio reports of the Good Friday Earthquake that had stricken south central Alaska. The epicenter was located in Prince William Sound, 78 miles east of Anchorage. The shaking lasted for more than four minutes and caused tsunamis, rockslides, widespread property damage, and the deaths of 139 people. With a moment magnitude of 9.2, it was and remains the most powerful temblor ever recorded in the northern hemisphere, and the second strongest in world history. Ambler, however, is nearly 500 miles from Anchorage. Those affected by the earthquake dealt with the aftermath, but life for the Cameron family went on much as usual.

Oliver and his family didn’t get much in the way of wages for their work in the store, though they got a break on groceries, so by the summer of 1965 it was time for Oliver to return to work in Kotzebue. This time he had been hired to build a church for the Episcopalians. Once the materials had arrived from Seattle by barge and he had checked the order, he studied the blueprints and then led a crew of men as they built the square log structure.

Oliver’s plan was to make the trip to Kotzebue with Richard, who would be working with him on the project, but Rene wanted the whole family to go. She argued that Oliver and Richard would need a cook and a laundress, and besides, the trip down the river in early summer would be lovely and relaxing.

Oliver’s position was that the river wasn’t the problem—it was the broad expanse of Kobuk Lake. Their boat was simply too small for the whole family to make the crossing safely.

Rene persisted. Richard was now 17 years old and would soon be leaving for college, and she wanted to spend as much time together as a family as possible. She was aware of the danger, but hoped that the lake would be calm. In the end, Oliver relented. Rene set about washing clothes and blankets, baking cookies and bread, and preparing the Ambler house for their absence.

On the day of their departure, they closed up the house and loaded the boat motor fuel, clothing, bedding, food, and dogs. By the time they were packed it was six o’clock in the evening. This did not deter them from leaving as they were eager to be on their way and the daylight would last for many hours yet. It was high summer, and the sun was still well above the northwestern horizon when they reached the encampment of archeological workers at Onion Portage at nine. They spent the night in the tent of a friend who was working on the world-class dig.

In the morning they enjoyed a hot breakfast of pancakes, meat, and coffee. Rene prepared a hot drink for the children consisting of water, sugar, and canned milk. Oliver accepted a friend’s loan of an extra 15-horsepower motor, promising to send it back on the first barge from Kotzebue.

At noon they stopped at an island where the mosquitoes were not too bad. The stop allowed them all to get out and stretch their legs, something the children especially enjoyed. Rene prepared a lunch of boiled meat, homemade bread, cookies, Jell-O and tea. Even in June it was cool enough at night to set Jell-O. Then they continued on and camped for the night on another island.

The next day they stopped and did some shopping and visiting in the village of Kiana, but then Oliver decided to push on to Kobuk Lake. He was becoming more and more anxious about the crossing, even though some of the villagers reported that the weather was calm.

He described what happened next in an interview with Ole Wik.1 (The Droop Snoot was what Oliver called their boat. He’d designed and built it with an innovative but peculiar keel line at the front end.)

There’s a little channel that takes off from the delta of the Kobuk and goes north through York’s lagoon on Kobuk Lake. I have forgotten the name. It was late in the day and was kind of windy, so I went that way. There’s a little lake at the end of the channel, just before you get into the lagoon. We camped there and waited for the weather to calm down.

The next forenoon it started to get a little better, so we went out to the entrance to the lagoon and waited a little bit. The weather seemed to be improving, so I took a chance on it, intending to get across the lake as quick as we could.

We started to go across the lake, intending to get on the south side of the lake that’s under the shelter of those hills over there, a little ways before Pipe Spit. But as you know, Kotzebue weather can change very rapidly. The wind came up from behind….

The waves were big. I had Droop Snoot, and it was loaded. The Droop Snoot was not an open water boat, and I knew it. I hadn’t built it for that purpose.

Anyway, the wind came up from behind us, so I started quartering across to the north side of the lake. I was heading for a little lake just west of Iqaluligagaruk. It’s almost a part of Kobuk Lake, except that there was a gravel beach separating it, and there was a tiny little channel that was just wide enough so you could run a boat through and get into still water behind the beach.

Richard was up in the front of the boat, and the rest were under a tarp in the middle of the boat. The waves were running along even with the gunwales. Once in a while a bigger waver would slop over into the boat. I was watching the waves very closely as we came to them. As I was coming to a bigger wave, I’d turn the boat so it wouldn’t plow into it, but quarter over it. Then I’d swing back north until there was another big wave.

I was just crabbing that way until we got to that little lake. The wind was against the beach and the waves were big, and I had to guess where that channel was and hope that it had not filled in with gravel.

I hit it OK, but the side of the boat rode up on the side of the channel. The water was knee deep at the edge, but the channel was deeper. I jumped out without even shutting the engine off and got the boat going and into the lake. We went around to the southeast edge of the lake, where it was out of the wind, and set up a tent.

When we got inside I was exhausted, just drained. I sat there and rested a little bit, just glad to be out of the wind and waves. So was Richard. He had been bailing the front of the boat while I bailed in back, with one hand. He would sometimes look at me as if worried, and I’d give him the OK sign and he’d go back to bailing. I don’t know what memories he has of that experience, but mine are vivid.

Afterward John Nelson told me that an old fellow had a boat. He always had a strip of canvas, maybe 5’ wide, fastened to the gunwales of his boat, on each side. In that kind of situation, he would throw that canvas out and let it float up on either side. A big wave would then lift the canvas, and the water wouldn’t come into the boat. I never tried that, but that was my last trip with Droop Snoot on Kobuk Lake.

According to Rene’s account, Oliver was white with fear. Neither she nor Gerald could swim, and none of them would have had a chance in such cold water so far from shore.

The wind continued to blow for the next six days, making it impossible to make the crossing to the Kotzebue side of the lake. There wasn’t much work that they could do beyond feeding the dogs and gathering firewood. Oliver worked on a dog harness, Rene knitted, and they did a lot of reading. The children braved the cold and played on the beach. Nobody had anticipated such an extended delay, and before long they’d nearly run out of food.

On the seventh day, with the wind still blowing and the lake still rough, Oliver decided that they would load up all of their gear and the dogs, launch the boat into the lake, and pull it along the beach by hand. He tied one towrope to the boat near the bow and another at the stern. By taking in or letting out the front rope, they could steer the boat so that it would travel parallel to the beach about 12 feet out from the shore.

They walked along in this way for several hours, taking turns pulling on the ropes. The only break in the monotony was when they were following a set of fresh bear tracks for a time.

Around two p.m., they saw a tent on the beach ahead. When they got there, they were pleased to find that it belonged to friend of theirs from Kotzebue, John Nelson. He was as surprised to see them as they were to see him. At first he thought that they had walked all the way from Ambler, but in fact they had “lined” the boat about ten miles.

They used the Nelsons’ tent to change into dry clothes, and then enjoyed a hot meal of baked sheefish, biscuits and coffee. Then they transferred their belongings to John’s large boat, tied the Droop Snoot behind, and crossed the lake to Pipe Spit and the home of Pete and Lena Satterlee. There they picked up the key to their rented cabin from Pete and Lena, and continued onto Kotzebue. By evening they were settled in. The next day was Monday, and Oliver and Richard reported for work as scheduled.

Oliver and Lorene had been close friends with the Pete and Lena Satterlee since the 1950s when the Camerons first came to Kotzebue. The Satterlees’ main home was on Pipe Spit, and they also owned a cabin in Kotzebue that the Camerons used when working. Pete was Norwegian—many Norwegian sailors came to Alaska and stayed— Lena was part native and part Norwegian. The Cameron family routinely stopped to see Pete and Lena whenever they passed that way, and over the years they became quite good friends. Pete had given Dorene a gold nugget and built Richard a model of a Norwegian sailing ship, both much-cherished possessions.

When the family returned to Ambler that fall, they found that the store was doing well. Oliver offered to buy it from Tommy. However, Tommy had other plans, so Oliver turned it back over to him and his family.

The summer of 1966 saw Oliver heading to Kotzebue for another summer of work. He would be in charge of building the parsonage to go with the Episcopalian church he and his crew had built the summer before. This time he and his family made the trip on the Bucky B with Tommy Douglas when he made his first run to pick up his barge order for the store in late June.

The boat had in inboard engine and was much larger than the usual skiffs that were in use on the Kobuk River. There was room to walk around on the deck, and it was comfortable inside. It was late June, and they stopped the first night at the edge of the river to catch a few hours of sleep.

Tommy crawled into his bunk, but the Camerons went ashore to gather birch bark from the trees near the river. They wanted to take a supply to a friend who made baskets to sell to tourists. They’d find a suitable tree, score the bark with a knife above and below the area to be removed, cut a vertical line between those score marks, loosen the outer bark, and peel it off in sheets as large as possible.

Though this left dark scars on the trunk that contrasted sharply with the remaining white bark, the trees were otherwise unharmed. Oliver also selected one straight, knot-free birch and cut out a length of the trunk for making frames for snowshoes.

The next day they continued on to the Kobuk delta. It was past midnight and the wind was blowing at 15 miles per hour, but they knew that if anything, it would be even stronger once the sun began beating down on the land. The Bucky B plowed right through the waves, although the dogs howled at the choppy ride.

It was nearly 5 a.m. by the time they arrived at Pipe Spit to pick up the key to their rental house in Kotzebue. Pete and Lena had been sleeping, so Oliver and Rene only talked with them for a few minutes before hurrying on their way. They assumed they’d have plenty of time to visit over the summer.

But as it happened, Pete only slept for another hour and then walked out onto the tundra to hunt ducks. Lena stayed home, nursing a sore back, but became alarmed when he did not return by dusk.

She searched for hours until she thought she heard his voice calling her. Moving in that direction, she came upon his body stretched on the ground. He had been dead for some time, likely of a heart attack or similar “medical event.”

Lena flagged down a passing tugboat and went to Kotzebue to get help. Oliver later helped move the body to town as the Satterlee family gathered for the funeral. Pete was buried near his cabin on the spit.

Once Oliver and his family got settled in Kotzebue, he turned his attention to building the parsonage. However, shipping a prefabricated cedar home from Seattle was not always a straightforward business. First of all, the barge was late, and when it did arrive there were delays in moving all of the components onto the building site. The work still couldn’t begin until the inspector had checked the building package, and he was also delayed.

Oliver decided to build a boat while he was waiting for everything to fall into place. The warehouse for Hansen’s Store was partially empty, awaiting the year’s shipment, and he got permission to use a portion of it as a workshop. He designed a boat that would be big enough to cross Kobuk Lake with no problems. It was 32 feet long by eight feet wide, and was covered with several layers of fiberglass and paint. He and the children worked on it daily.

It was a thrill when they launched the boat, mounted a brand new 45-hp outboard, and took their first ride. By the time they headed back upriver at the end of summer, Oliver had added a cabin and had purchased a catalytic heater to keep it warm on the long trip. He also added a more sophisticated steering system.

Photo from the Cameron Family Collection.

The family returned to Kotzebue in the summer of 1966, but things began to change over the next couple of years. Richard headed for Fairbanks and the University of Alaska, and his absence was keenly felt.

Photo from the Cameron Family Collection.

Dorene studied alone at the desk—most of the time—that Oliver had built for them until Gerald finished attending the Ambler elementary school and joined her for high school home study through the University of Nebraska.

Photo from the Cameron Family Collection.

Oliver also continued to study and refine his own philosophy of life. One of his dreams was to establish a Bible School in Ambler in order to share his religious beliefs with others. For her part, Rene had long dreamed of a better house, and in 1966 they began building a new, larger home farther from the crumbling riverbank.

Photo from the Cameron Family Collection.

The closer this new house came to completion, the more restive Oliver became. Even though the old house was dangerously near the unstable river bank, something about moving into the new place troubled him. Perhaps he felt the house was too big, taking too many resources. In the end, in spite of his wife’s hopeful dreams, he chose to follow his own inner beacon. God’s plan, he announced, was that the new house was not for the family to live in after all, but was meant to be used as the Bible school.

For Rene, this was the last straw. Oliver had become ever more determined to leave a small footprint on the earth, to use a minimal amount of resources to survive. Rene was a woman who valued nice things and a comfortable home. Oliver had moved away from an orthodox Christian belief system, fashioning his own philosophy based on his interpretation of the Bible, while Rene remained solidly evangelical Protestant in her beliefs. One thing that helped her endure the hardships and deprivation of life in Northern Alaska was her belief that she had been called there to minister her faith to the local natives. Oliver also felt a sense of divine purpose, but their understanding of that purpose had diverged substantially. These interpersonal tensions resulting from their differing values and religious beliefs, along with the demands of their strenuous lifestyle, had undermined both her physical and emotional health, stressing her to the breaking point.

She returned to Idaho in late summer, 1969. By that time Dorene had finished her high school studies; she remained in Ambler with Oliver. Gerald went with Rene to Nampa and enrolled in a private Christian high school.

Oliver and Rene divorced in 1970.

1Ole Wik and Oliver first met when Ole came to Alaska about 1963. An engineer and surveyor who had turned down a scholarship for graduate school to live in Alaska, Ole built a sod house with friends in Ambler.

Appendix

Onion Portage

Onion Portage is the site of a world-class archeological dig about 12 air miles west of Ambler on the north side of the Kobuk River. The Camerons passed it every time they went downriver, often stopping to visit with friends who worked on the project. The American archeologist J. Louis Giddings located the site on his first visit to the Kobuk River Valley in 1940. He was the first to use dendrochronology (the study of tree growth rings to determine timing of events and changes in the environment) to date Arctic artifacts, and he applied this technique to the discoveries at Onion Portage.

Onion Portage takes its name from “Paatitaaq” meaning “wild onion” and referring to the abundance of onions that grow at the site. The “portage” part of the name refers to the loop of the Kobuk River that, at this point, creates a long peninsula between two sections of the river. Travelers would cut across the peninsula from one portion of the river to the other to save going around the long bend, or oxbow. “Portage” is used to mean the transporting of goods or boats between two bodies of water, or of the route itself. In this case it refers to the route, used by both people and wildlife. The native peoples congregated there specifically because of the abundance of wildlife. Fishing was good with lots of sheefish and several species of salmon. Caribou used the portage on their migrations north in the spring and south in the fall, making it an ideal location for the native hunters to intercept them as they crossed the river. Due to the abundance of resources, the site has been one of continuous human occupation for more than 10,000 years. This makes it a remarkable archeological resource.

When Dr. Giddings first identified it as of possible interest for research, a few house pits were excavated, but work was interrupted by World War II and Dr. Giddings’ other projects. In 1961 he returned to the site and identified multiple occupational layers, perfectly preserved and going down several feet. In the course of his investigation he discovered thousands of wooden, bone, and stone artifacts. The collection of this data has had far-reaching implications for the entire region, shedding light on native populations and habits over thousands of years.

In 1964, the year after the Camerons moved to Ambler, Dr. Giddings began a major excavation of the site. A cabin was constructed for him by some local Ambler residents, which continues to stand. Tragically, Dr. Giddings was in a car accident in Rhode Island and died in December of 1964. He was only 55 years old.

The site continues to be significant for the study of Arctic history. The National Park Service owns the five-acre homesite and the cabin which is not open to the public, but is kept in honor of Dr. Giddings and his work. In 1972 the Onion Portage Archeological District was declared a National Historic Landmark and listed on the National Register of Historic Places.1

1https://www.nps.gov/kova/blogs/peeling-back-the-layers-at-onion-portage.htm The National Park Service: Peeling Back the Layers at Onion Portage, Jan Hardes, September 12, 2013.