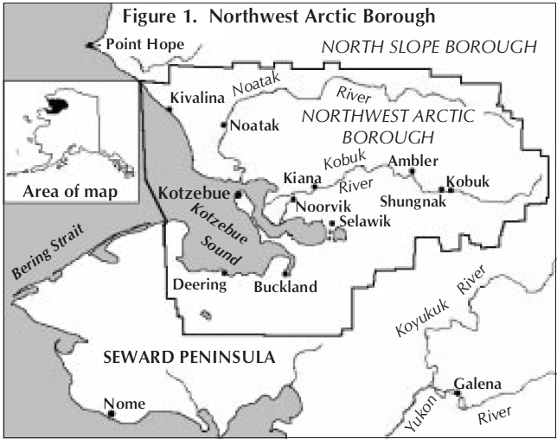

Kotzebue lies about 30 miles above the Arctic Circle and a little over 400 air miles northwest of Fairbanks. It is accessible only by plane, or seasonally by boat. It is situated on a narrow spit of land that has long been a popular gathering and meeting place for native peoples, since it lies near the confluence of three major rivers: the Kobuk, the Noatak and the Selawik. The Kobuk River would figure prominently in the life of the Cameron family for years to come.

When the Camerons arrived in 1955, its population stood at 1,000, primarily Inupiat Eskimos. The Camerons shared the plane to Kotzebue with a large tour group. The tourists had priority at the only local restaurant, so the Camerons had to wait. They were stuck on the beach with their belongings until Chester Savok and his wife noticed them. This native couple was hired by Wien Airlines to dress in their finest parkas and greet tourists as they landed.

Photo from the Cameron family collection.

Once the visitors had left for their tour of the village, the Savoks took Oliver and his family under their wing. They gave them a ride into town in the “tour bus,” a pickup truck with benches along the sides of the bed for seating, and then helped them unload their gear and set up their tent near their own house.

The next day Oliver and Rene introduced themselves at the local Friends Church mission. The pastors, Harold and Hulda Beck, invited them to move onto the mission property while Oliver looked for work. The summer sun shone day and night, giving them plenty of daylight to move their tent and belongings.

Oliver had included a 15 HP outboard motor in the supplies he brought with him. He soon built a boat, covering it with canvas and marine paint. With the aid of the little motor he was able to get firewood.

Photo from The Cameron Family Collection.

Oliver favored living off the land as much as possible, so he also set a net in order to take advantage of local salmon to supplement their food supply. This helped a lot, since the move had consumed much of the family’s funds.

They camped for the rest of the summer, with Rene helping at the Friends Church and the children attending Vacation Bible School.

In his search for work, Oliver became acquainted with a prospector by the name of Gene Joiner. He had staked claims on a large jade deposit at the end of the Brooks Range about 150 miles east of Kotzebue, and was known locally as the “Jade King.”

In 2004 June Allen wrote of the area:

There are no highways that reach into the far northwest region of Alaska’s arctic [sic]. Even air travel is restricted to small planes. There are few visitors to the little Eskimo villages along the Kobuk River, a sizable stream that winds its way along a 200-mile route from its headwaters in the Brooks Range to Kotzebue Sound and the Chukchi Sea.

The river keeps well above the Arctic Circle en route. It rolls through a landscape of birch, spruce, poplar and willow and then courses through rolling tundra as it nears its ocean destination. The Kobuk is busy with local boat and barge traffic in the short ice-free summer months and with snow machines in the winter….

There are no contemporary hiking trails or campgrounds along the river’s route, but there are small Eskimo villages…this remote Kobuk Valley has been home to people for perhaps 12,000 years!

She goes on to say that anthropologists from the University of Alaska began researching the people and the area in the 1930s. They’d heard stories about a mountain of jade, which turned out to be true.

Gene came to Oliver and asked if he could weld a sled that was capable of hauling a twenty-ton block of jade across the tundra from the mountain to the Kobuk River. From there it would be floated on a barge into Kotzebue. Tundra might appear flat and featureless, but it is actually pockmarked with rises, hillocks and mounds and crisscrossed with gullies and ravines. On two previous attempts, both his Caterpillar dozer and his sled had broken down attempting to traverse the difficult terrain. It took Oliver a week to design and weld an appropriate sled for the job. For the Jade King, the third attempt was a charm. The Nome Nugget, “Alaska’s oldest newspaper,” reported:

A huge block of genuine jade weighing more than 20 tons reached the arctic port of Kotzebue last week after a five year 200 mile trip from the mine at Jade Mountain. The owner, Imperial Jade Company of Kotzebue, who operates the mine, has kept the huge block of gemstone intact as it is by far the largest piece of fine jade ever found. Although containing approximately 4,000,000 ring sets, the block will not be used for this purpose. Imperial Jade, which exports jade to all parts of the world, feels that its size and quality would ruin the jade jewelry market for all time. This block, maximum measurements 5 X 5 X 16 feet, will be sold for the purpose of carving into an outstanding monument. For the time being it will be kept in storage by Gene Joiner at Kotzebue. At the time of this writing, it still sits in Kotzebue.2

This block seems to have become the stuff of legend. Joiner had a contract with a buyer, a well-known political figure, but the deal fell through. As the world traveler and writer Gail Howard reported on her 1956 trip to Kotzebue:

…on the edge of town lay a huge boulder of pure jade just sitting there in the middle of nowhere. The jade was meant to be carved into a life-size statue of Eva Peron. But when Juan Peron was overthrown by a military coup in 1955, the plan for the statue and the jade were abandoned. I’ve often wondered if that huge hunk of jade weighing tons, carelessly covered in a white shroud, is still there, and if not, what happened to it.3

Oliver continued to work with Gene for a time, cutting jade, fixing mining equipment and even repairing an airplane to sell. At one point they flew to the mining town of Candle for ten days, a 45-minute flight from Kotzebue. Gene was a daring pilot and known for his failure to file flight plans. They had some close calls, at one point getting home with a mere three quarts of gas in the plane’s tank.

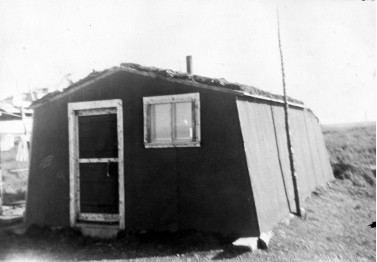

As summer turned to fall and the weather became too cold for their tent, the Camerons rented a small two-room house owned by Irving Smith and located next to his on the beach. It was neat and clean and they were cozy there, with oil heat and a two-burner Coleman stove for cooking. Oliver attached railings to a large tool chest for toddler Gerald’s bed. The older children slept in a bunk bed. Closets were neatly covered with curtains, clothes were folded in wooden Blazo boxes under the beds. The small windows were kept covered with blinds to conserve heat during the short winter days.

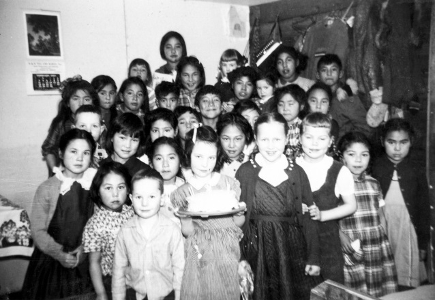

Dressed in warm hooded parkas with ruffs and mittens, the Cameron kids played happily outdoors with large groups of local children. Their wooden box full of toys also drew the neighbor children into their small house, where two-and-a-half year old Gerald was a favorite of everyone.

Photo from the Cameron Family Collection.

Rene joined the Mother’s Club in order to make friends among the native women. They taught her how to remove the sinew from the muscles alongside caribou backbones by pulling apart the fibrous strands and twisting them together to make strong, durable thread, and then how to sew sealskins and furs.

They also taught her how to create mukluks, mittens and jackets. They used caribou leg skins for the upper parts of mukluks, and made the soles out of the tough and durable skin of the bearded seal (ugruk). At the very top they added a drawstring to keep the snow out.

Rene learned to size the mukluks so that there would be room for a layer of dry grass, a felt liner, and two or three pairs of socks that she knitted herself. Everybody also had a pair of rubber boots for wet weather, and Oliver had hip boots as well.

Rene also had a treadle sewing machine that she used to make clothing for her family. She melted snow to wash clothes on a scrub board.

Photo from Cameron Family Collection.

As the holiday season approached, the family made their Christmas tree out of stacked Blazo boxes.5 They began receiving packages of clothing and food that had been collected for them by their church in Fairbanks. Rene was able to add luxuries like pasta to their diet of caribou and fish, as well as other treats.

Much to Rene’s (and the children’s) delight, the holidays also saw a flood of gifts and toys from family and friends in faraway Colorado, Idaho, Oregon and California. By that time Oliver had acquired three sled dogs, and made use of them in hauling packages from the airport.

Holiday celebrations at the Friends Church lasted a full week. Residents gathered every evening for several hours.

Photo from the Cameron Family Collection.

Many went home about 9 p.m., but a smaller group stayed on into the wee hours to play games called qitik. These included contests to see who could kick a ball the highest, as well as games of strength of the finger, arm and leg. On New Year’s Eve they rang the church bell for 45 minutes, and some of the men soaked caribou skins in gasoline and burned them outdoors.

Rene and the children enjoyed the festivities. They also participated in the local community and church programs, which included lots of food, entertainment and gift-giving and also offered them a good introduction to the local culture.

Photo from the Cameron Family Collection.

Oliver, however, kept his distance. He was growing less comfortable with many of the traditional teachings of the Protestant churches around him. It also bothered him that the missionaries to the native Alaskans maintained a higher standard of living than their parishioners, and seemed to have a condescending attitude toward them.

During that first winter the town magistrate, George Francis, asked the Camerons to house-sit for a week. They were treated to a large, modern house with a pantry full of “luxury” foods like those they had left behind in Idaho. A tall floor-standing cuckoo clock, with a little bird that popped out to mark the time, left a lasting impression on the children.

At the end of the week they moved back to their snug little house, but not for long. One frightening night, Oliver woke to a scream coming from their landlord’s house next door, where his grown son was staying. The son was quite drunk and had trapped his girlfriend’s head between the door and doorframe as she attempted to get away from him. Oliver ran over and ordered the man to stop. When he refused, Oliver jerked the door open and freed the woman. The drunk then took a swing at Oliver, so Oliver punched him all the way back to the back room, knocking him out.

Oliver reported the incident to the magistrate. He also apologized to their landlord and his wife. Their son was a well-known troublemaker, so they didn’t press charges. However, the son insisted the Camerons be evicted from the cabin, and the parents, wishing to keep peace in their family, asked them to move out. They found another place to live. Sometime after this event, by March of 1956, they were running low on funds for heating oil. Oliver had some work prospects, but these were limited by his refusal to take a job that would take work away from a local Eskimo.

Oliver’s desire to live off the land, to avoid a conventional lifestyle, and his growing distance from orthodox Christianity led to increased tension between him and Rene, who retained the beliefs and values with which she was raised.

Their situation was looking dire when they were invited to set up camp on the shore of Hotham Inlet at a place called Iqalluligagaruk, meaning “creek with fish,” about thirty miles northeast of Kotzebue. There they could live in their tent on the shore for a few weeks and burn wood for heat, saving the expense of heating oil. Several other families were already there and would provide help and company. Oliver was eager to try his hand at ice fishing, and this looked like a solution to their problems as well as a step toward Oliver’s goal of a more sustainable, living-off-the-land lifestyle.

The day of the move to fish camp came. The temperature stood at 20 degrees below zero. Oliver had gone ahead with his slow, three-dog team while Rene carefully bundled the three children into their warm winter clothing—pants, shirts, sweaters, wool socks, mukluks, parkas, mittens, caps, scarves and hoods—and then left them to wait on their friend’s sled in sleeping bags while she donned similar clothing.

While she was dressing, their friend began to hook up his 20 dogs. Sled dogs become extremely excited when they think they will go for a run, yapping and jumping at the end of their chain while waiting for their turn to be placed into the harnessed string of dogs. Suddenly, the friend was unable to hold the dogs any longer, and the team took off without Rene, but with her three children still on the sled.

Nearly distraught that her children were on a 30-mile dog team trip in intense cold with neither parent, she waylaid a neighbor and convinced him to hook up his own team. She and the neighbor followed in hot pursuit. By the time they caught up to them at the first stop, John Nelson’s cabin, she was thoroughly chilled. The children, however, were fine—warm, filled with hot chocolate, and playing with other kids.

They reached their destination without further incident and set up their tent. Their 10 by 12-foot tent was very tight for a family of five and their winter gear. The beds were in the back end of the tent, with the stove and a Blazo-box table in the front. They sat on logs to cook and eat, and spent as much time outdoors as possible to avoid the cramped conditions.

In spite of the cold and the uncomfortable tent, the Camerons were privileged to have been initiated into a fishing haven. Hotham Inlet, locally known as Kobuk Lake, was famous for spring ice-fishing. The people would cut holes in the ice and jig for sheefish, often using homemade ivory lures.

The fish were fat, had delicious white meat, and ranged from six to eighteen pounds. Large schools of them moved around under the ice. If one of those swarms passed your chosen spot, you could catch incredible numbers of fish, one after another. This happened to Oliver. One day he surprised his family by coming home with 132 fish.

Oliver was in his element, but Rene struggled to care for herself and her family in the primitive conditions. They burned wood for heat and basic cooking, but their stove had no oven and she was unable to bake the breads and biscuits she was used to serving. Fish and rabbits were plentiful—they were even used as dog food—but other foods were in short supply. In the six weeks they spent in fish camp, she lost fifteen pounds.

Richard was now old enough for school, and Rene (who had a degree in teaching) had taken on the responsibility of his education, continuing his studies through homeschool lessons while they were in fish camp and away from the local school in Kotzebue. Oliver would hitch up his small dog team and make runs to the post office in Kotzebue, bringing new lessons that had come in the mail. When Rene made reading flash cards for Richard, preschooler Dorene learned along with him, gaining skills that impressed the teacher later back in Kotzebue when she herself began classes.

When summer came, the family broke camp and moved back to Kotzebue for the summer of 1956, setting up a green army tent east of the village on the tundra. Oliver worked that summer for a company called Bullock’s, a tug and barge business.

Since Kotzebue doesn’t have a natural harbor, the boats that brought supplies from Seattle during the ice-free summer months had to anchor fifteen miles out. Bullock’s lightered [A lighter is a large flat-bottomed barge used to transport goods from cargo ships.] the year’s supplies to the beach, where crews of casual laborers unloaded them for transfer to a nearby warehouse.

Supplies for each village were stored in separate areas of the warehouse. As water levels permitted, smaller tugs and barges took the supplies upriver to their assigned villages. Once the warehouse was empty, Oliver again found himself without work. He decided to move his family back to fish camp. By late September they had settled into a white army tent on the beach at Iqalluligagaruk.

Eager to live both sustainably and comfortably off what the land could provide, Oliver set about to improve his family’s living conditions. He built a new stove, complete with an oven, out of a 55-gallon oil drum. Rene made good use of it, keeping her family supplied with hot bread, pies and muffins. It was now summer, so their diet included berries with their fish and rabbit, supplemented by potatoes from Dr. and Mrs. Fitz in Fairbanks and goodie boxes from relatives in Idaho. It took a lot of time to cook hot meals, but the five families in camp shared the work and food, creating close bonds and good memories.

They spent the pleasant fall days hauling wood, picking berries and checking nets for fish. One day they found eight varieties of fish in the net: tomcod, trout, sheefish, northern pike, flounder and three varieties of whitefish.

They washed clothes on the beach with a tub and scrub board, and hung them to dry on tent lines or bushes. Baths for the children involved a small tub near the stove; however, this once resulted in a bad burn when someone got too close to the hot metal. Rene made a hat for Oliver from rabbit skin, and the northern lights regularly put on a show for them.

With winter coming on, Oliver decided to build suitable shelter for his family and stay near the fish camp.

While the children worked on their lessons with Rene, Oliver got started on a winter house. He leveled off a 13 by 15-foot site about half a mile behind the beach and began digging. Richard, who was only eight but bright and curious—he liked to peruse the thick Sears mail-order catalogue in his spare time—also worked on the house. He helped Oliver build and still kept up with his schoolwork.

By the first of October Oliver was working on the house every day, but the weather was getting colder. The snow became deep and the wind blew through the trees surrounding the white tent. Soon the lake was frozen over and they were keeping the fire going all night to stay warm. Oliver or Rene would get up a couple of times a night, open the draft on the stove to let it burn hot, fill it with wood, and go back to bed. Rene tried to keep the children to a minimal school schedule, but the family’s main focus was on finishing and moving into warmer quarters.

In keeping with his desire to draw on the wisdom of the local peoples who knew how to survive in the harsh climate, Oliver had chosen to build a style of house called an ivrulik—Eskimo for “wintering place.” He put four corner posts in the ground, connected at the top with stout horizontal poles. From the top corners, other poles slanted upward to a center post with split logs around a square center opening, which became a skylight in the roof. For the walls, he leaned small poles against the horizontals, six to eight inches apart. He also framed in a couple of windows.

He covered this simple framework with three layers of heavy polyethylene sheeting, rectangular slabs of moss, and a final layer of dirt. Since the poles were at a slant, gravity held the moss in place. The end result was a very tight, warm structure.

On moving day, it took several trips to get all of their belongings from the tent up to the new house. They put spruce boughs on the floor, and from time to time the children went out to gather fresh boughs to keep it clean.

Photo from the Cameron Family Collection.

As Christmas drew near, food boxes from their church in Fairbanks again supplemented their menu. Meanwhile, in Kotzebue, another big, week-long Christmas celebration was planned.

They were settled into their snug, but isolated, ivrulik when Oliver made a trip to Kotzebue for supplies and more schoolbooks. While he was there, some friends strongly urged him to bring the family to town to participate in the festivities. At first he was reluctant, since it was a big job to move the family in the cold at the darkest time of year, and he had just finished the tight little house with a view toward staying in it the entire winter. However, a couple of other men offered to help, and he bowed to peer pressure and his family’s longing for social connections. Rather than move to town just for the holidays, then move back, Oliver and Rene decided to spend the rest of the winter in Kotzebue.

On moving day, Oliver and Rene sent the children ahead with friends, and followed with their own sled. Oliver had arranged for seven dogs to pull his sled. At first the borrowed dogs did not work well together as a team, but eventually the family all made it safely to Kotzebue.

They stayed about a month with the Don Roberts family, who had a beautiful Christmas tree that the whole family enjoyed. By January, 1957, they had moved into a small trailer house behind the mission. They bought an oil heater for warmth, and re-enrolled the children in the Kotzebue school.

Later that winter they moved into a snug, two-room cabin owned by the town magistrate, George Francis, exchanging work for rent. This was not the large house they had once house-sat, but a smaller cabin built for George’s wife that was meant to be used during the summer fishing season.

The house was made of lumber, and was well insulated. It had a large enclosed porch, or arctic entry, that operated as a heat seal. It kept the warm air in when they opened the interior door, and also served as a place to brush off snow before entering the main living space and as storage for mukluks and parkas.

Rene and Oliver’s double bed was to the left of the entry. The bunk bed stood across the room, with the kitchen area in the corner behind it. The oil stove was along the back wall, near the doorway into the second room. That room contained the owner’s belongings and was not used by the Cameron family.

In another corner under the only window was a desk where they read and did paper work. Like most in the village, they used a Coleman pressure lantern for light. Oliver improved the situation by adding a large front window to the main room.

Dorene turned seven in February. Since space was limited for a birthday party, they invited only a few friends, not realizing the local culture did not recognize “by invitation only.” When thirty people showed up for the party, they quickly adjusted and made room, playing games and eating lots of cake and Jell-O. Everyone had a good time.

Photo from the Cameron Family Collection.

As the winter progressed, however, they again faced hardship as Oliver could not find work. One morning the family woke up to find only bread and oatmeal for breakfast, and nothing in the house for lunch. With impeccable timing, a neighbor came across the street to tell Oliver the electrician’s helper at the school had not reported for work, and that the contractor needed help immediately. Oliver went to work as a temporary substitute. Once he knew that he had the position, he went to the store and bought groceries for his family, on credit. He stayed on the job for six weeks.

Their house faced west, which meant that snow from the big east wind storms drifted around the front porch and entryway. The drifts were high enough the children could use cardboard as sleds and slide off the house and into the street. At that time the streets were not plowed during the winter, and the only traffic was foot traffic and dog teams.

By May it appeared that the winter storms were over, so Oliver headed back to their ivrulik at fish camp to retrieve their personal items. He planned a three day trip by dog sled, leaving Rene and the children snug in the house.

It proved to be an exhausting trip for Oliver. At nearly every step of the thirty miles, he broke through the softening snow to his knees. Meanwhile, a late storm nearly trapped Rene and the children in the house. Fortunately the owners, who lived next door, came to the rescue and helped clear the drifting snow away from the entry.

Photo from the Cameron Family Collection.

That summer Oliver and his Eskimo friend Charlie Jones used a homemade sawmill to make lumber, fighting the mosquitoes when they went across the lake and into the timber to collect the logs. Charlie used his share of the lumber to build a boat, while Oliver built a house in front of John Nelson’s place on the beach.

While we were living there, I made a little house and had made a cache out of opened out barrels….That house was just barely big enough, because that was all the lumber I had. I built a lean-to onto the back, and a skylight in the top of the lean-to. If the dogs started barking, I could stand up on the bed and open the skylight to see what was going on.

Oliver knew there were huge ice floes when the ice began to break up in late spring. The jumbled ice was sometimes forced up onto the beach, clearing everything in its path, so he set the house on skids in the hope that it would just move with the ice.

Photo from the Cameron Family Collection.

He laid vinyl over the lumber floor, and Rene hung curtains at the windows and over the cupboards. The children’s bunk bed and little Gerald’s own short bed were in the front room. Oliver and Rene slept in the added lean-to, which also served as the laundry room.

Oliver seems to have continued to work periodically for the tug and barge company during this period, and maybe did a little jade cutting. He also put his truck driving skills to use when the Territory of Alaska began a significant upgrade of the Ralph Wien Memorial Airport, replacing the runway, adding a taxiway and an aircraft parking apron, and building an entrance road.6

They started to build the Ralph Wien Memorial Airport. Before that they had just used a little dirt strip behind the town. I got a job driving truck on that airport. They had done what I was doing with my truck: took a little truck and made a big truck out of it. Of course, when you do it, some parts aren’t designed for it. The axles in the drive wheels were one of those parts….There were three other drivers who were breaking axles because they didn’t understand how to drive without putting on too much pressure, but since I had had one of those trucks, I understood how to drive….

Finally, the boss got put out and said, “The next guy that breaks an axle gets his check.”

Well, I was the next guy. I dumped my load and drove up to the shop and fixed my own axle. The boss didn’t say anything. He needed me.

Meanwhile, Alaska was changing. World War II and the following Cold War had revealed the territory’s strategic importance, and its vast natural resources were becoming apparent. By 1958, after much controversy and delay, Alaska was moving toward statehood.

In keeping with the times, the City of Kotzebue incorporated in 1958, organizing with a mayor, city manager and seven-member city council. Most of the new government leaders were Alaskan natives, but Oliver was also elected to the city council. Since he had received more votes than any other candidate, it was assumed that he would be the council president. However, he declined that position, choosing instead to be secretary.

Since this type of government was new to most of the residents, they related to the new council as they had to their more familiar tribal leadership. They considered Oliver a chief, and came to him to resolve all kinds of disputes. He often had to refer them to the appropriate authorities, such as the local magistrate.

In the fall of 1958, as representatives were being chosen for the first Alaskan State Legislature, Oliver was asked to run as representative from Kotzebue. He was honored, but declined. Statehood was officially granted in January, 1959.

About this time Oliver, in keeping with his goal of a self-sufficient lifestyle, began to think about another major move, even further into the wilderness, up the Kobuk River to the village of Shungnak.

___________________________________________________________________________

1 June Allen. SitNews, “A Legendary Mountain of Jade,” October 5, 2004. http://www.sitnews.us/JuneAllen/AlaskaJade/100504_jade_mountain.html

2The Nome Nugget. Source: Lorene Cameron, More Than A Story.

3Gail Howard. Gail Howard’s Territory of Alaska Travel Adventures Before Alaska Was a State. http://alaskatraveladventures.org/

4Gail Howard. Gail Howard’s Territory of Alaska Travel Adventures Before Alaska Was a State http://alaskatraveladventures.org/alaska-photos/index.html. Used by permission.

5”Blazo” was Chevron’s brand of white gasoline. Two square five-gallon cans were packaged in light wooden boxes, which were themselves very handy.

6The Ralph Wien Memorial Airport Terminal Area/Land Use plan of 1983: Airport history. Thanks to ARLIS Reference Services, Alaska Resources Library & Information Services, Anchorage, AK.