A little over two years later, in 1988, Oliver sat in his snug cabin writing a letter to Dorene. Engrossed in his writing, and sitting in the well-insulated cabin that retained the heat, he failed to notice the fire dying down until it was nearly out. When he did notice, he added more wood, and then checked the outside temperature: -40°. He resumed writing, telling Dorene the coldest he had seen at his new home was -45°. It did not usually get that low at this new location, unlike Shungnak and Ambler where such temperatures were the norm, but later that winter it would drop to -60°.

This was unusual, even in the interior of Alaska. The 1988-89 winter would long be remembered for the record-breaking cold over most of Alaska, except the Aleutian Islands and the Southeastern section. An unusual combination of high pressure systems and other weather quirks resulted in widespread sub-zero weather, with Fairbanks experiencing temperatures lower than -40° for six days in a row. Then, in January, a pressure system moved in from the North Slope and the weather got worse. According to the Anchorage Daily News, “…records toppled at every weather station west of a line from Manley Hot Springs to Lake Minchumina.” 1 Oliver, with his snug cabin and his new, efficient handmade stove, survived the unusual cold just fine.

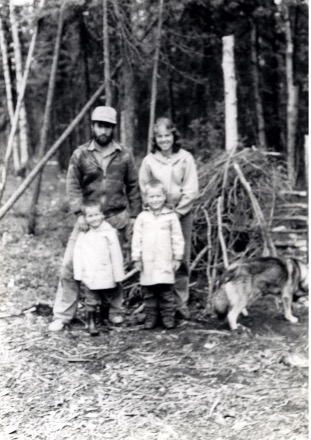

Photo from the Cameron Family Collection.

The original little five-gallon can stove he had used his first winter in the lakeside cabin had burned out. When the heavy winter hit, he had just finished a new stove, and was working on a small camp stove made from stainless steel stove pipe that would be used for heat in a tent on his camping trips.

It was just after Thanksgiving and Oliver was tentatively planning a trip to California for a visit with Dorene and her family in June or July to allow for more activities with his grandchildren during summer vacation and warm weather. A friend had heard on the radio that Santa’s Travel Agency in North Pole, Alaska was advertising a special on round-trip tickets to anywhere in the lower United States. The tickets only cost $368 and were good for a year, but he needed to purchase one before December 31.

Oliver had not heard about the tickets earlier because he only listened to the radio for the news and for Trapline Chatter—a message service of radio station KJNP of North Pole, Alaska, which provides communication to people in the villages and in the Bush who have no quick means of reaching family and friends. A message might be a birthday or anniversary greeting, or news of a package sent, or a visitor arriving. Oliver had recently caught up on family news via a Trapline Chatter message. Now he was responding with a letter, a slower form of communication as he had to wait for someone available to take the letter to the nearest post office. This letter was going out with a friend on his way to Fairbanks in a few days.

During these cold winter months Oliver worked on indoor projects. He often used the term “chink-time” for projects he could do in odd moments. He was working on the little camp stove, and was thinking of making a belt loom for a friend who was learning to weave. He had collected about half the needed skins for a rabbit-skin blanket, commenting that he had “’bout cleaned out the rabbit population in the area.” The rabbits, of course, were eaten as a fresh source of protein in addition to lending their skins to the blanket. When such game was unavailable Oliver was forced to eat groceries shipped in from outside, to the detriment of his digestive system. He fared best on his subsistence diet of wild meat and fish supplemented by local berries and greens from his garden.

Over the past couple of years he had developed a good relationship with his nearest neighbors, Jill and Dennis Hannan and their little boys, Shaun and Stormy. Oliver was helping Jill learn Morse Code. Oliver believed she was far enough along to pass the ham radio license exam, but she felt shaky and wanted to continue studying until she was more confident. In a few weeks, after the holidays, Jill would make her annual trip to Fairbanks to sell furs trapped by her husband, Dennis, and get supplies. Oliver hoped she would take the exam then. Dennis would stay home with their two boys while she was in town as he hated both “going to town” and shopping. It was an arrangement that suited the couple, allowing Jill to indulge her love of shopping and her need to socialize.

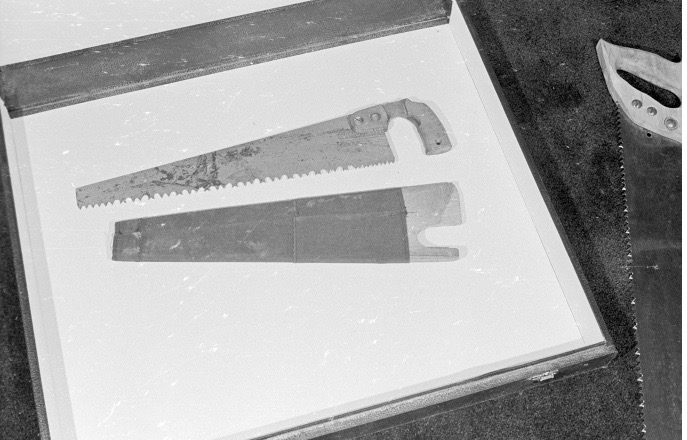

Photo from Cameron Family Collection.

Right from the start the Hannans had aided Oliver in his quest to set up a new homesite in the remote area. It had been so late in the year when he finally picked the site that he had resigned himself to living in a tent for the winter. Instead, the Hannans got busy and helped him dig out a ten by twelve foot square about four feet into the ground for a small cabin, stacking up the log walls an additional three feet and adding a roof, Visqueen, and sod to give him better shelter for the winter. This was intended to be a temporary cabin until he could get one built that would meet the BLM requirements to “prove up” on his claim. Contrary to his expectations, the cabin did meet the requirements for the BLM, and he continued to live there for several years.

When spring had come that first year, Oliver began adding other structures to the site such as a cache and a dog house. Eventually he put in a garden and fenced it, although he tended to raise plants that were unusual in a garden—a “self-starting” garden, Jill called it. He grew what many considered weeds: alfalfa, coltsfoot, chickweed, sour dock, lambs quarters. Oliver had discovered the health benefits of these plants, and their natural tendency to reseed themselves saved him energy that was better spent elsewhere. The Hannans, meanwhile, stuck to more traditional crops like carrots and lettuce.

By now life had settled into a routine, but Oliver was not relaxing, even cabin-bound during an Arctic winter. He remained as industrious as ever, saying he felt under pressure to get some things done before the warm weather arrived, including more writing. His book, Thoughts Born of Turmoil, was published, but he was thinking of revising it to reach a wider audience. He wrote Dorene:

There seems to be a lot of people feeling insecure, unsettled and worried, and maybe some of the thoughts I write about may be an encouragement to a few people.

In spite of hopes and plans, Oliver was both impatient and discouraged during his third winter in the small cabin. By spring he would have spent about two-and-a-half years at the site, but progress toward a truly comfortable home was painfully slow. Occasionally he had doubts: what was he doing trying to start over at his age? In another two-and-a-half years he would be 70. He should have had a place fixed up so he could relax a bit and just tend to the daily routine. Then he reminded himself that life wasn’t meant to be easy, that he was still learning and growing and this project was part of a larger plan for his life. “A rocking chair,” he wrote Dorene, “would just be a short ride to the “gate” for me, and I’m glad for this place and opportunity, most of the time.” He would be less gloomy, he added, when spring came and he could be more active, but it was still winter and the snow was more than knee-deep.

His old snowshoes were not suitable for the deeper, softer snow he now encountered. He had recently begun crafting a new pair that would work better at his current location. First, however, he had to make a rip saw. The design of a rip saw was something he had spent many years perfecting. He believed he had now made the saw the best it could be, and enjoyed working with it. After the snowshoes, he planned to cut boards for a new boat.

As winter gave way to spring of 1989, Oliver had more messages via Trapline Chatter, and worried about the reliability of his mail system that depended on sending letters out by whoever happened by. He thought perhaps he should start keeping a written record of letters sent and received. He fretted that a letter might have been lost, or perhaps Dorene’s reply was held up in Nenana, the nearest town connected to the outside world by road.

The winter went by with more events to keep Oliver engaged: A contractor who had been hired to rebuild the air-strip at Minchumina tried to haul his equipment in overland during the winter while the ground was frozen. The route went by Oliver’s lake, and about seven miles past his house the lead caterpillar went through the ice and into several feet of water which then froze solid. They waited until the weather warmed up, then pulled the cat out. When the construction company had supplies and fuel flown in, Oliver took the opportunity to send mail out with the pilot.

The correspondence school supervisor, who visited on a regular schedule (Shaun and Stormy were homeschooled) had failed to show during the worst of the winter, and Oliver and the Hannans were anticipating her soon arrival. As the winter wore on, Oliver kept busy with his projects. He finished the stainless steel camp stove—as well as a new tent—with a view toward camping trips to gather food. The weather had warmed up, but that turned the trails into a slushy mess, so Oliver still stayed close to the cabin and finished preparations for his food-gathering trip, planned for later in the spring.

The new tent was made from two fire-resistant nylon pup tents Oliver had purchased the summer before, taken apart and reassembled into a larger six by eight-foot wall tent. It weighed only a little over three pounds and folded compactly into his sled.

During this time a newspaper reporter contacted Oliver requesting an interview. Oliver’s first response was that he “wasn’t interested in that sort of thing.” Still, he and the Hannans shared reading material, and one day at their place he checked out the reporter’s style by reading one of his articles in North and News about a family living a subsistence lifestyle. Oliver reconsidered the reporter’s offer, realizing there was the issue of “influence.” Might his story do some good by reaching a wider audience? He often wondered about this when his need for privacy conflicted with the calling he felt to influence and educate others.

By mid-February, 1989, the weather was warmer, although Oliver still needed firewood. He was feeling better, and was not so stiff when he went out walking.

First 50 years I lived rather carelessly and took my body more or less for granted. Now for 20 years I’ve been reaping the consequences, but hope to regain good health again. I’ve been studying and trying to do what I can see to do toward that end, and I have hope.

When the Minchumina area was opened for homesteading in 1982, hundreds came to stake claims, but only a few remained. In addition to mail and Trapline Chatter, the three closest neighbors who had stayed in the area kept in touch by CB radio. Every evening at the same time the households turned on their CBs and chatted about daily events. Those keeping tabs on one another were Oliver, Dennis and Jill Hannan, and Duane and Rena Ose. The land set aside for homesteading by the Bureau of Land Management, the 30,000 acre Lake Minchumina Land Settlement Area, was near the edge of Denali Park. Oliver and the Hannans were along a lake about a half mile from one another. Duane Ose had staked his claim on a hilltop with a view of Mt. Denali (Mt. McKinley) about eight miles away on another small lake. While Duane and Rena Ose started out in a dugout cabin much like Oliver’s, they were building a three-story log house, much to Oliver’s chagrin. Oliver, a minimalist, believed in leaving a much smaller footprint on the land. Duane seems to have found Oliver a bit eccentric as well, but they remained respectful and friendly, Oliver staying with the Oses at various times over the years as well as talking on the CB every night.

By spring Oliver grew impatient with saving up rabbit skins and made a small blanket from what he had. He planned to add to it later. By June his alfalfa seed was up about three inches. He wrote:

Dennis sowed some kind of grass seed on his house and of course chickweed came with it so I transplanted some to my garden. There is some pigweed growing with the alfalfa so eventually I’ll have pigweed & chickweed mostly in my garden. Would like to plant some chives next year, too.

In August Oliver went to Fairbanks, primarily for medical treatment. Upon his return he wrote:

Am sure glad to be home again, and getting rested up a bit. The trip to the big city was a hustle, bustle experience with very little time to relax. But I did get most of what I went for done—two hernias patched— year’s supply of medicine and some other supplies and the rest of the stuff I really wanted brought out from Manley.

He felt he finally was completely relocated from his former home in Manley Hot Springs. As he healed from his surgery, he also kept busy, cutting the alfalfa which was now about a foot high, and spreading it on a tarp to dry. He continued to make plans for his camping trip to hunt and gather food and hoped to pick a couple gallons of blueberries before he left. Some of the supplies acquired in Fairbanks included a 55-gallon plastic garbage can to be put in the ground and used for storage of berries, oil, and other perishable foods. He had also brought back items to keep his radio and CB working, and a scope mount for his .270 rifle. With the addition of a flashlight attached to the gun, this would enhance his ability to view and discourage predators around camp at night.

Oliver continued to refine his communication system. While the radio connections were now satisfactory, and he was reasonably confident he could get a message out in case of an emergency, the mail delivery still left something to be desired. While in Fairbanks he arranged with pilot and guide Jack Hayden to deliver his mail in the summer, and air-drop it in the winter. This seemed a more reliable system to Oliver, and from then on he had his mail forwarded to Jack’s address in Minchumina.

Another thing he did while in Fairbanks was answer a personals ad he found in a friend’s Ruralite magazine, connecting with a woman of his age in Oregon. She had responded, but he maintained he wasn’t expecting much beyond friendship. He had a hard time imagining someone able to share his lifestyle, and felt wary of the complications of close relationships.

Dorene had sent him mixed vegetables, but he finally gave up trying to eat them when they caused too much digestive upset. It was late fall and he had had to increase his prednisone medication (for his lungs), something he hoped to reduce again in the near future. Instead of the mixed vegetables, he ate willow leaves he had collected and dried the spring before, mixed with his own dried greens, as well as imported green beans and celery. He planned to preserve more willow leaves as well as chickweed from his garden. The young willow leaves, called “sura,” are about ten times richer in Vitamin C than oranges.

The willows that the Eskimos on the Kobuk like —sura—are strong tasting here. The moose seem to especially like them and the tips of all of them are eaten off….The felty leaf willows and another one similar to it are the best tasting here. I’ve been taking about one-quarter of the leaves for each bush I pick.

Oliver stored his dried willow leaves in seal oil. This was a technique borrowed from the Inupiaq and was a very good way to preserve the nutrients in the greens and vegetables. To keep it fresh, the oil was stored in a cool, dark place which also helped preserve the leaves and vegetables. The oil prevented air from reaching the plant material and destroying the Vitamin C. Other oil-soluble vitamins, like A, D, or E would be infused into the oil and ingested when the oil was eaten. This system preserved the vitamin content of the willow leaves, or any other edible plants, for quite a long time.

Oliver had also located a large patch of bluebells near his home and would include those in his diet.

1989-90 was an “old-fashioned” winter for Oliver, although there was no repeat of the unusual cold of the previous year. From his November 5, 1989 letter:

We have had snow, snow, snow and more snow, more than we have had since I’ve been here. Where the wind has packed it or blown it away the lakes are frozen, but the swamps are still just slush under the snow.

By the year’s end Jill had returned from Fairbanks with the flu, which Oliver caught and was having trouble getting over. He finally consulted his handbook, Folk Medicine & Arthritis by Dr. Jarvis, and decided he was short on iodine. He remedied that, and soon felt better.

Once again confined to the cabin by winter weather, he began work on various indoor projects including cleaning and organizing. He got an old bicycle with a bicycle generator kit set up and was able to generate enough power by cycling to run his radio, or a flashlight, or a small light for reading.

Earlier in the year Oliver reported seeing a marten—a long slender-bodied weasel about the size of a mink— chasing a rabbit. Now, by mid-winter the martens had decimated the rabbits around his house and Oliver was left wondering how to snare enough to enlarge his rabbit-skin blanket.

Spending more time indoors during that winter, he began building a ten-foot long “touring” sled since the make-shift sleds he had available were not suitable for a longer trip. The sled took up a lot of room in the little house, but he made good progress on it, finishing it before the winter was over. Oliver hoped to travel to Lake Minchumina, using his current dog to help pull the sled. He had continued to keep an eye on the “cat trail” left by the contractor working on the Lake Minchumina air-strip project. The trail seemed adequate for Oliver’s purpose. His mail had been piling up at Lake Minchumina since November, and by March he was more than ready to make a trip to town, snaring rabbits along the way. Dennis, his trapper neighbor, had told him where the rabbits were located. He planned to take Jill and the young boys along as Dennis was off on a job earning money for the family and Oliver did not want to leave them alone. Before they could make the trip, however, the “cat train”—the heavy equipment used by the construction company—came along and then broke down (again), requiring a pilot to fly supplies out for repairs; the pilot also brought Oliver’s mail. The equipment was repaired and moved on out, but tore up the trail in the process making it impassable for Oliver and his sled. Besides, the main point in the trip to Lake Minchumina had been the mail, now no longer an issue. He, Jill, and the boys were “all dressed up with no place to go,” so they turned their attention in the opposite direction. About ten miles away was a family with children the same age as Shaun and Stormy. In fact, Stormy and Tara, one of the children, had birthdays two days apart, so they went for a birthday party and stayed three days. The women were able to visit, the children played together, and Oliver hunted rabbits.

Oliver kept busy, but occasionally he had time to reflect. That winter he wrote Dorene:

I hardly ever think back or ahead, but once in awhile something like your birthday will bring a flash of recognition of the panorama of our past history and it seems like some sort of dream. I don’t really know how to describe the feeling it brings. It’s as if I suddenly became conscious, then you children came and each went off on your own life course like a shooting star, and now all of sudden, I’m an old man getting near the end of my stay here….Then I come back to the present reality of my life, the day to day plodding along whittling away at the accomplishment of long range goals while mostly preoccupied with the daily chores of living….

Oliver was 68 and more than twenty years from the end of his stay here. As the decade of the 1990’s opened, new opportunities for growth and adventure would present themselves in unexpected ways.